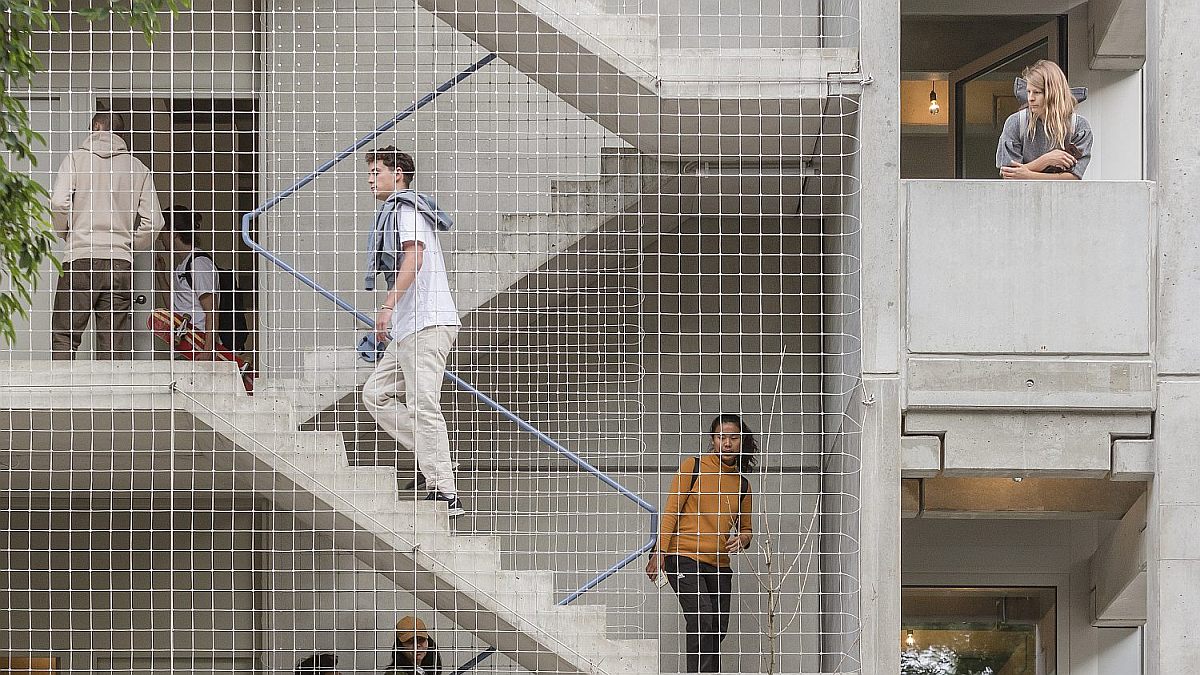

The project makes it possible to completely renew the site, and on a more global level, to think about collective housing and the environmental approach to it. Both employed on this plot to create a new urban pattern that may generate of good quality and sustainable development.

Articles box

ASTRA VR is a museum project which uses VR technology, sound installations, and cartoons to make traditional culture heritage much more accessible. ASTRA Museum of Traditional Folk Civilization undertook to innovate its means of expression and to come closer to a new generation of visitors.

Introduction

Text: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

As you probably know, the “Roșia Montană” natural and cultural site was included on this year’s UNESCO’s World Heritage list. This is, of course, a tremendous joy, the result of fierce battle which was fought, in varying proportions, by hundreds of thousands.

But this is not what I want to talk about here, but about what I learned, while reading this year’s list and then a few from the past few years.

Text: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Twenty years ago, I officially started my work in this magazine’s management team. Well, it had a different name back then, and had a different status, but it was still an independent publication. When I say management team, I burst a bit into laughing, because that team was also the editorial team, and even the design one. Up to 2004, it was the same three people – Cosmina Goagea, Constantin Goagea and myself, who would also take care of marketing (that is, advertisement money), and the backpack distribution.

The conservation project for the cemetery church of Ursi Village, Vâlcea County, Romania, represents an exemplary case study (rural acupuncture practice) for a specific larger group of wooden churches included in this 60 Wooden Churches programme, designed in 2009 and coordinated by the Pro Patrimonio Foundation.

The “Wohnregal”( “Dwelling shelf)” is a 6-story building in Berlin housing ateliers with integratd dwelling.

Text: FAR

Photography: David von Becker, Tobias Wootton

We are living in post-Communism in Romania, that is, in a country still defining itself by its relationship to its Communist past. After a long tradition of invented mythologies and counterfeit identities, we are searching for real history. In order for it to exist, we need witnesses and memories to acknowledge, even when shameful. And this is where the museum steps in, with its possible role of mediator, of negotiator in this process of understanding and learning, and, perhaps, ultimately, of healing memories that hurt.

An almost collapsed house. Volonteers. Real restauration instead of the easier reconstruction. The fragile house becomes a means for a bottom-up cultural program and a hope for the local community

text authors: Mirela Duculescu, Andreea Machidon, Raluca Munteanu, Raluca Știrbăț, Șerban Sturdza

photo: Camil Iamandescu, Raluca Munteanu, Șerban Sturdza, Pro Patrimonio

*George Enescu House, about 1920. Dr. Ștefan Botez archive

*George Enescu House, about 1920. Dr. Ștefan Botez archive

Intro

Mirela Duculescu, the chronicler

Architecture serves society. Heritage buildings that were rescued and naturally integrated in the economy of contemporary life, youth education, recovered crafts and consolidated communities, these are the fundamental directions for the Pro Patrimonio Foundation. The Foundation seeks, devises rescue and restoration models, finds and offers solutions for heritage as an economic, cultural and environmental resource.

An illustrative case study is provided. In 2013, an exceptional pianist meets an architect that doesn’t fit any established pattern, , and signals the disastrous state in which she had found George Enescu’s house, in the Mihăileni village, Botoșani County, on the border with Ukraine, in a high risk area (depopulation, poverty, failing community cohesion).

*existing situation, april 2014 ©Raluca Munteanu.

*existing situation, april 2014 ©Raluca Munteanu.

The architect listens to his instinct, strategy and lifetime expertise. The peasant household, in a shocking state of decay, with definite architectural qualities (intricate planimetry, based on the golden ratio), is deemed fit for demolition by brethren and authorities.

*Existing situation, Aprilie 2014 ©Raluca Munteanu.

*Existing situation, Aprilie 2014 ©Raluca Munteanu.

Nevertheless, it is a classified historical monument, since November 2013, Code LMI BT-IV-m-B-21063, due to the pianist’s stubbornness. There ensues a declaration of emergency situation for the building, the step by step conservation and restoration, synchronous with the complicated stage of searching for valid models of integrating the house in everyday life, alongside the community, beyond architecture.

7 years later, on August 19, 2020, the restoration site for George Enescu’s house in Mihăileni closes, and the composer’s memory is honoured by a concert given by the pianist. In fact, one stage closes, the one of restoring distressed rural heritage, and another one opens, that of using-living the space through education and musical culture for the community, a future core that may become a centre of excellence in the study of sound.

The entire endeavour was an enormous joint effort, coordinated by Pro Patrimonio, aided exclusively by private entities, an entire army of natural and legal persons, who supported, financially or in kind, the entire restoration process.

2020 was the celebration of 20 years since the Pro Patrimonio Foundation was set up in Romania by architect Șerban Cantacuzino.

We have the house, we have the land, we have to have the community as well!

Șerban Sturdza, the architect of strategic exploration

I was sitting comfortably with several friends in Radu Miclescu’s mansion in Călinești, when I happened to learn of the Enescu house in Mihăileni. I hadn’t been aware of Raluca Știrbăț’s efforts of rediscovering the history of the place, of her and her mother’s travels in the surrounding villages, and, ultimately, of the bumpy endeavours she had already undertaken. My friend, architect Alexandru Beldiman, had already seen the ruined house and had told us it was almost impossible to save. That is when I realised the possible core of this story, a small architecture object which, should one be able to save it, would become a very good example for so many forgotten places in Romanian culture. The project’s quintessence was well shaped before me. Saving this small building was scheduled without having seen it. It engulfed the essential Romanian issues (see Brâncuși’s house, etc.). Why should there be a restored Radu Miclescu Mansion, and not a restored George Enescu House, just 35 km away, when Eminescu’s Ipotești was just 15 km away from where I sat?

The rescue model lies beyond architecture, in the social needs of the place and in a conversation with Mr. Ovidiu Ionică, a local and entrepreneur builder. He told me that, if we were to repair the house, “we could also send our children here to take music lessons.” Right then, or perhaps a little bit afterwards, I realised something which in time became reality: the house and its architecture were a pretext, what mattered was how to set it up and running again, with whom and how could one build a site for education. Nothing mortified, nothing museified, everything used, and not just randomly, but at the highest level.

After a careful analysis of the physical aspects, leaning over the building’s surveys, amazed at the proportions and relationships between spaces, I re-discovered a few regulating trails and geometric relationships contained in the architecture plan, and I perceived the object differently. I am now stating that we are not looking at a regular peasant house, but at an architecture plan that took a long time and a great deal of intelligence to elaborate, a house that was inhabited by an accomplished, well-educated family. Suddenly, the existence of a piano in this house became mentally acceptable – in fact, it was a returning of the instrument where it had always belonged – and a plan of intervention started to take shape.

Instead of a construction firm specialising in restorations and of the usual experts with their stamps and CVs, I preferred an analysis of local limitations, and then to work with common local technology, and people who knew how to make and re-make, every now and then, with simple means, the mandatory parameters of living. Amazement struck when, seeing the house ruins, the locals recognized the common things which were so unknown to us: the iatac (bedchamber), the stove-wall, the custom of sleeping on the oven, the workings of the cellar with its ventilation system. The only chance to achieve the project with a high degree of authenticity was the claca[1] – a joint effort, shared by the neighbours, and rewarded with wine and brass band music.

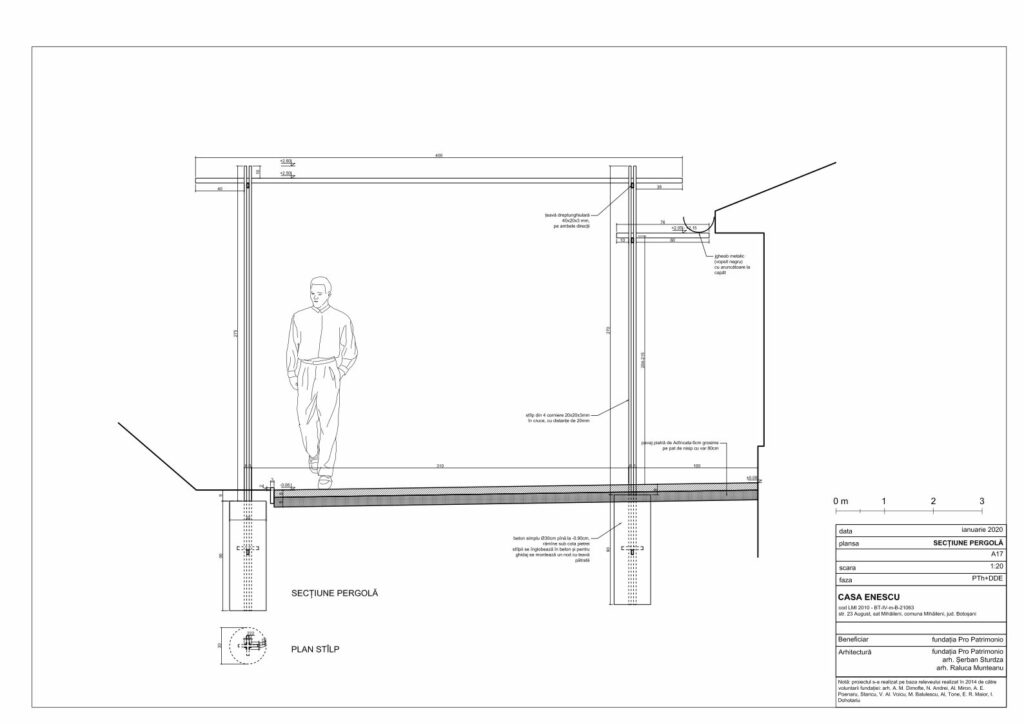

I have continuously balanced the project and its achievement between two extremes. On the one hand, physical work, using the original substance (clay, straws, manure), the brutality of the technology, dictated by throwing the clay at the walls from a distance and binding it by force, but also the gentleness of the last clacă, the “good hand” of local women. On the other hand, inviting Tudor Patapievici, a student architect at that time, to do his BA thesis, under the coordination of Professor Dan Marin, on the plot across the road from the Enescu House, with a necessary theme: a centre for musical education and music research, a project which, when finished, had us delighted with the result, and convinced all those involved that, for sure, this project would have continued to execution stage, had things taken place in Switzerland. There was a chance for creating a landmark in the Bucovina area…

We have the house, we have the land, we have to have the community as well. The topic remains music and sound research in general. We are looking for collaborators and investors to raise awareness to a project with a huge potential, which few people acknowledge now: a centre for excellence in music and the study of sound. The size of the building and the fact that it is far away, somewhere in the north, a few hundred meters off the Ukraine border, does not diminish its power and, let us not forget, George Enescu is increasingly discovered by the international world. Watch out.

The profession is constantly adapting, before the eyes of the community. Conservation principles

Raluca Munteanu, the architect who won’t give up

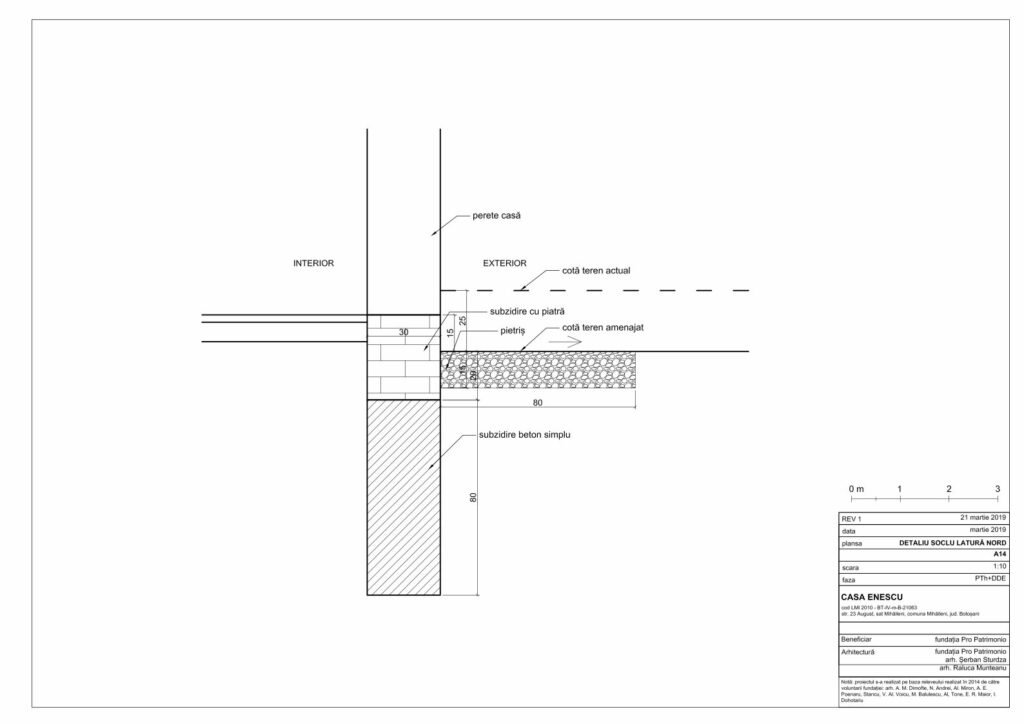

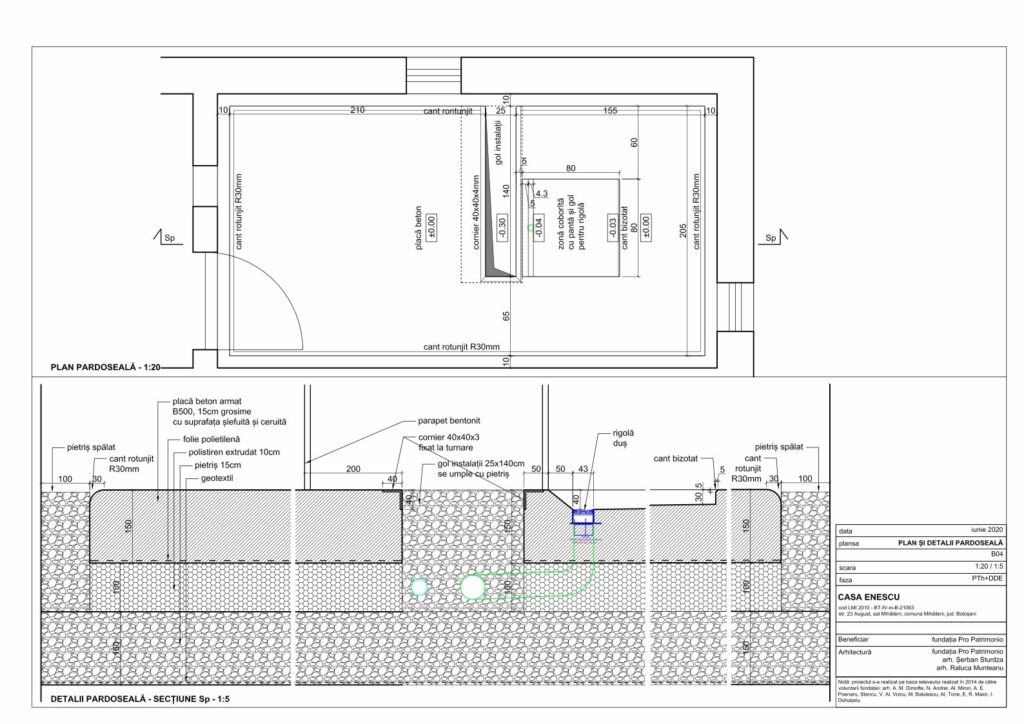

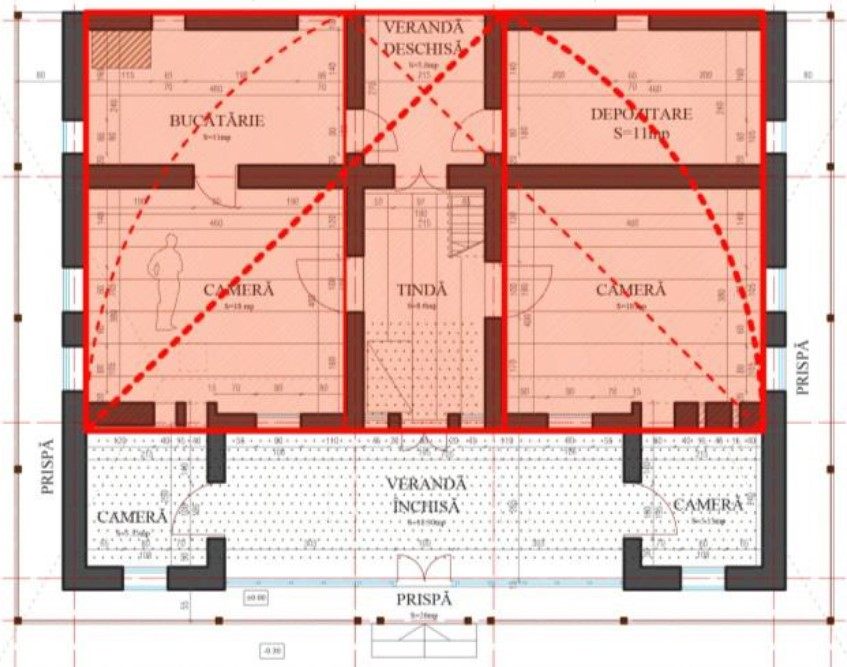

The George Enescu House in Mihăileni, Botoșani County, is a simple, provincial house, symmetrically organized, with the planimetric organization and elevation defined by the golden ratio: two 4x4m living rooms, each communicating with two 2x2m iatace (bedchambers). Each communication is done via a stove-wall, a rare and novel architecture element. The main facade has a glazed-in porch, which leads to a central hallway, accesing the two large rooms, located on both sides of the hall. The access hatch to the (half, stone-built) cellar is also found in this hallway, as is the access ladder to the attic. At the far end of the hallway, one reaches the two rooms under the polata (eaves), one functioning as a kitchen, with a cooking stove, the other meant to be a larder. On the outside, the house is surrounded on three sides by a narrow veranda.

In 2014, the house was in a state of near collapse. Rain and snow coming through the roof, which had degraded year after year, had affected the half-timber walls and the wooden structure. The house had been abandoned for years, unkept, its cultural value forgotten. The first natural step was an emergency intervention to remove the danger of total collapse, which seemed imminent with the arrival of autumn rain and snow. The energies of many young architects and students, coordinated by the Order of Architects, the Bucharest and North-East Branches, were accompanied by a local team and, during several weeks, managed to provide some support to the house, to protect it from water and to clean up the interior, taking inventory of the objects found and of the house’s schematics.

*Emergency intervention, Aprilie-May 2014 ©Pro Patrimonio.

*Emergency intervention, Aprilie-May 2014 ©Pro Patrimonio.

In parallel to the efforts of shedding some light on its legal status and of raising funds for restoration, as architects, we tackled the issue of how to rehabilitate the house. An oak-structure building, on a not-so-deep dry stone foundation, with walls filled in with clay and straw, is one that hardly falls under the usual intervention practice. The crafters suggested demolishing and rebuilding it by the same techniques they still mastered. The suggestion did not seem wrong, given that most of the structure seemed compromised, and that the craftsmen’s knowledge in reproducing the execution technique seemed satisfying. Nevertheless, in the current context when reconstructions are accepted too frequently and too easily (even in the absence of traditional materials or without reproducing the execution techniques), the Pro Patrimonio team, led by Architect Șerban Sturdza, reached the conclusion that it was more important for the work to become an example for the principle of preserving the historical substance, than it was to get a new, improved copy. Besides, the approach also had an important psychological impact on the community: the building did not vanish from the site, and all the repair steps could be observed, so that both the locals, and the wide public, could see that a ruin could be reborn.

*Conserved wooden structure, 2015 ©Raluca Munteanu.

*Conserved wooden structure, 2015 ©Raluca Munteanu.

How was the work done? The unstable stones in the cellar walls were taken out and built in with lime mortar, the roof structure was propped up with adjustable cast-moulding metal rods, and the cracked and damaged filling was taken out of the walls. The walls, cleaned of impurities (whitewash and rubble debris) were completed with clay, sand and manure, and was reused to fill in the walls. Before filling up the walls again, the wooden structure was checked and completed with the missing wooden pieces, or the damaged elements were replaced. The clay filling and finishing was done during three traditional clăci (2015-2016), where the local community, volunteers from neighbouring villages and project supporters from all over the country came together and worked all day long accompanied by the sound of a brass band of Hilișeu-Horia, and shared a meal prepared by the locals.

*Remaking the clay filling of the walls, first „claca” ©Raluca Munteanu.

*Remaking the clay filling of the walls, first „claca” ©Raluca Munteanu.

The entire outer woodwork was also repaired by local master carpenters, preserving even the 2mm small hand-made glass panes found on-site. The missing panes were replaced by glass of the same quality from other houses in the village, where the locals did not want to keep them, or from ruined houses.

*Remaking the stoves ©Pro Patrimonio

*Remaking the stoves ©Pro Patrimonio

Another difficult decision was to introduce sanitary facilities in the house, as present need of comfort and hygiene demand it. But a house built on a half-timber structure is sensitive to water. Where initially the agreed solution was to have an independent annex to house sanitary facilities, up to the end the larder was transformed into a bathroom.

*left – The bathroom / right – The kitchen ©Camil Iamandescu

*left – The bathroom / right – The kitchen ©Camil Iamandescu

To limit the risks of contact between the water installation and the clay walls, sanitary objects were grouped together at the centre of the room, on an independent parapet, made of modern materials (metal structure and asbestos cement), to ensure easy maintenance and optimal use. The room preserves unaltered its whitewashed clay walls.

From the experience of this restoration, we could find some lessons for architects: no matter how badly damaged a building is, the architect must analyse, first and foremost, how they can preserve as much of the historical substance as possible, before deciding to create a copy. Authenticity and original materials increase the value of the place and have an impact on the community, an impact we often undervalue. Another important aspect was collaborating with locals at the level of ideas, as both the restoration solutions, and the manner of using the house after repairs were born out of these discussions, which were not thought out from behind the drawing board.

… Enescu places the moment of the golden “ratio” (Goldener Schnitt) with mathematical precision….

Raluca Știrbăț, the pianist

The Enescu house in Mihăileni came into my life unexpectedly, as a natural consequence of my wanderings on Moldovan lands, searching for Enescu-related musical and biographical paths. I was in no way prepared for many of the things that were to follow, but I shall not speak here of the chagrin caused by the indifference – opposition even, hard to understand when it came down to a discreet, but valuable Enescu monument, the only one preserving the authentic architectural and emotional substance of an old house built and inhabited continuously by the composer’s family.

The true surprises were related, on the one hand, to discovering some intimate aspects in the life of the composer and that of his family – complex aspects, worthy of a volume of their own – as well as to Architect Șerban Sturdza’s findings regarding the regulating paths and the presence of the golden ratio in an apparently simple, yet discreetly elegant architecture.

*Golden rectangle in the organization of the plan ©Șerban Sturdza

As a musician with an older passion for mathematics, the aesthetics of proportions or the mysticism of Matila Ghyka’s golden number (by the way, Matila Ghyka was born in Iași in the same year as Enescu), I am looking in my music sheets for the more or less visible structures, guidance in the intricacy of complicated sound languages, especially that of Enescu. Just like his idols – the “three great Bs”: Bach, Beethoven, Brahms – Enescu places the golden “ratio” moment (Goldener Schnitt) with mathematical precision and genius spontaneity in the return of the main theme at the beginning of reprises or in the most sensitive moments of the composition.

Just as surprising, claca, the “good clay” or the “good hand”, where women – with their slender and nimble hands – are caressing the soft and moist texture which is to become the wall of the house, was, to me, a unique sensory experience, besides the emotional involvement and the actual “lending a hand” to rebuilding Enescu’s house.

*Last touches to the clay walls, the so-called „good hand” made by women, „claca” ©Raluca Munteanu.

*Last touches to the clay walls, the so-called „good hand” made by women, „claca” ©Raluca Munteanu.

At the time, I was amazed by the substance similarities in barehandedly moulding a clay house and the kneading of bread dough or a new music piece one discovers, remodels and rebuilds, immersed in the piano keys and penetrating the composer’s deepest intimate universe.

I also want to share the moment when the piano came, when I felt – perhaps, with an excusable subjectivity – that, 7-8 years of efforts later, the house had finally regained its “soul”, with the Bösendorfer becoming a sort of axis mundi in a mini-universe of Mihăileni. And yet, perhaps it was not that ‘mini’, if we were to remember the auditory-sensory revelation of a 3 year-old Jorjac (”Georgie”) Enescu, dissatisfied with the four strings of his toy violin, which he could not use to compose, and the experience which would ultimately mark his destiny as a composer:

“Over the summer, going to my mother’s house in Mihăileni and seeing the piano there, on which my mother used to play, I immediately asked that we take the piano with us […]. It was now so good to let myself wander among chords! A glass of water to a thirsty man could not provide more joy!”

Conquering the land through education

Andreea Machidron, the enthusiastic architect (“our Miss”, as the children in the village of Mihăileni would put it)

We created the Education for Heritage Caravan in 2015, as a strategic instrument addressing mainly children and young people in the sometimes poor and de-structured areas where Pro Patrimonio is carrying out projects. The workshops are aimed at education and direct learning, through experiment and creativity, about architectural heritage, memory, local identity, relationships between people, nature, buildings, and cultural values.

*Education in heritage, atelier with the children form Mihăileni, 2020 ©Andreea Machidon

*Education in heritage, atelier with the children form Mihăileni, 2020 ©Andreea Machidon

The caravan reached Bucovina, in Mihăileni for the first time in August 2020, where 20 children attended an intensive program dedicated to heritage, to discovering the Enescu house and to creatively exploring local resources. One of the most beloved activities was the one aimed at sound education. The vibrations of various surrounding materials were used as starting points in an attempt to map the sounds of the place, of comparing them to voices and instruments and to ingeniously use them to build hand-made instruments, eventually tuned in an impromptu orchestra. And as historians, the children researched and found the history of the house and of George Enescu’s memories of it, creating an animation dedicated to the place.

Info & credits

Place: sat Mihăileni, jud. Botoșani/Mihăileni village, Botoșani county

Construction: 1775-1830

Emergency intervention, conservation, restauration: 2013-2020

Historical monument code: LMI BT-IV-m-B-21063

Program: MUasic and Sound Study Academy, memorial building

Owner: Pro Patrimonio Foundation

Architecture :

Project responsable : Șerban Sturdza

Team: Raluca Munteanu, Tudor Patapievici

Architects, volonteers for the survey: Lucian Rădulescu, Natașa Andrei, Mădălina Bălulescu, Alice-Maria Dimofte, Elena Rucsandra Maior, Alexandru Miron, Andra Eliza Poenaru, Diana Stancu, Alexandru Tone, Vlad-Alexandru Voicu, Ionuț Dohotariu, Răzvan Stanciu.

Craftsmen for emergency interventions and clay walls restauration : the team led by Ovidiu Ionică

Finishes, installations, interior refurbishment: team lead by Gabriel Drancă, DMG House & Building SRL

Plot area (sqm): 1267

Built area (sqm): 134

Partners:

International ”George Enescu” Foundation, Vienna, Remember Enescu Foundation, UiPath Foundation, The Prince of Wales’s Foundation Romania, Popovici Nițu Stoica & Asociații Attorneys at law, Radu Miclescu Foundation, Chamber of Romanian Architecs – Bucharest and North-East Branches, Color Magic Sikkens Romania, Geberit Romania

Private funds :

Emergency intervention : 10.000 Euro

Restauration: 85.000 Euro

[1] A Romanian and Hungarian costum – an short and intense period of construction, for which all members of a community collaborate. The construction can be public or private (when, in time, everyone’s turn comes).

ADN BA have had the opportunity to insert small buildings in sensitive urban areas before, but that has usually happened in the garden districts in the north side of Bucharest. In this case, the context has an older history, being part of the extended historical centre, more eclectic (a mixture of buildings of all styles and sizes), but also rich in landmarks and symbolic spaces of the city.

In what follows we will talk about a example of reconditioning and re-use of an existing dwelling space. The importance of such a project cannot be stressed enough, no matter how much is written about the subject. We live in a highly built world which constantly presents us with the opportunity to reinvest buildings with the facilities necessary to contemporary generations, thus salvaging energy, resources, and a dash of memory.

On 27 July, during the 44th extended session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, the Rosia Montana mining landscape was inscribed simultaneously on the World Heritage List and on the List of World Heritage in Danger. On this occasion, Sneška Quaedvlieg – Mihailovic, Secretary General of Europa Nostra, delivered a powerful statement, strongly applauding this decision and recalling the support of Europa Nostra to this campaign, also with the support of the European Investment Bank Institute, during the past decade. Europa Nostra is also preparing a congratulatory letter addressed to the Romanian President Klaus Iohannis, who himself welcomed the inclusion of the mining landscape in these important lists.

Intro: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

This short dossier starts in fact before the introduction you are just reading. The opinion piece on rural space and the recent works of the Larix Studio closes the dossier on village architecture; it also includes a public space project, one of the most persecuted programs in a rural world that has to deal with underfunding, migration and abandonment, but also with individual interests and poor civic association.