Text: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

The charm, the issues, and the potential of the suburbs. Densification in a fragile environment

Let me tell you a story about the school of architecture and the suburbs. A few years ago, following a very inspired choice by the department, the workshop of the “Ion Mincu” University of Architecture with the 2nd -year students had the locations of both 1st-semester projects in the Andronache neighbourhood, towards the North-Eastern margin of Bucharest. A historical Bucharest outskirts neighbourhood („mahala”), if you will, namely a (mostly orthogonal) network of streets dating back to the early 20th century, with narrow, deep plots, built, over time, with deep narrow houses attached to one side of the plot; a mix of rural and urban, in fact a denser, better shaped and more organized rural (from the very start, there were a park and a church), with people who used to work in the city and, at the same time, would also tend to the garden and a few animals. Up to a certain point, the neighbourhood underwent a slow urbanisation and a successive building on the plot, following the traditional Bucharest custom. Then, an accelerated development: paving, becoming part of Bucharest, and then, over the past decades, an accelerated and wild building of houses and then increasingly higher blocks of flats, unrelated whatsoever to the scale of the place and devoid of any logic or strategy.

The first project was imagined by the theme’s authors as a way of getting used to the neighbourhood: a careful study, followed by a small-scale intervention (the second project was a detached house). I remember how confused our students were, how confused everyone was, in fact. Considering these were their first projects on a real site, they would have liked a nicer place, perhaps a historical one, with clear values, in essence, with certitudes and models. They could not understand why banality and non-architecture represent a context worth considering.

They were not happy with the first walk, although, once they forgot they were architecture students, they could not help but find a little joy at the sight of a vine, be amused by the extreme DIY of some households or by the decorations on some fences.

*Learning from Andronache neighbourhood as architects

*Learning from Andronache neighbourhood as architects

Well, as they had to walk around holding their sketchbook, undertaking research criteria, talk to people (that was one firm requirement from us), their attitude started to shift. They were discovering a world, the fact that behind buildings and architecture there are people with desires, possibilities, techniques, ingenuity, they would start to understand the neighbourhood structures, the social practices and their connection to the spatial ones, the hierarchies, the passage from public to private, the intermediate spaces. In fact, we discovered alongside them that it is precisely the lack of aesthetic qualities that facilitates the discovery of these discrete values.

The projects varied immensely, from the rehabilitation and reinterpretation of former fountains, to a food market or to building a semi-clandestine shop for an elderly and poor lady. One of the projects, authored by the now-architect Daniela Popescu, developed the largest difference of scale between analysis the proposal that I have encountered so far as a teacher. Daniela drew an entire street, in plan and in views: drawing it, she understood it better and better; at some point, she discovered a nearly invisible entrance and, behind it, a hidden household; her actual project consisted of a minimal development of this entrance and this road. I chose a fragment of this analysis as the main illustration of this first part of the article.

*Daniela Popescu, Ion Scorțan Street, Andronache neighborhood, București

*Daniela Popescu, Ion Scorțan Street, Andronache neighborhood, București

Let this be well understood: my support here is not for nostalgia or for living in the past. The urbanization and radical change of the build substance in former suburbs, today’s more or less marginal neighbourhoods, is completely unavoidable and, in fact, follows the expansion logic of Bucharest and of towns outside the Carpathians: let it be said, on the side, that there are also many towns in Transylvania sporting this type of neighbourhoods, most of them from the inter-war period. It is quite clear that people in these areas are also entitled to space, comfort, representation.

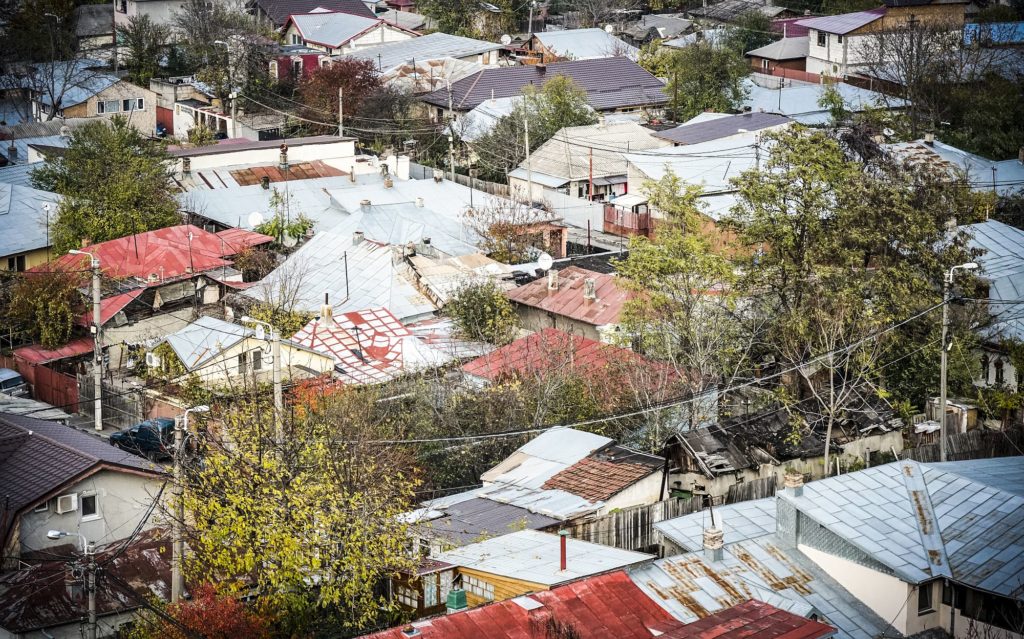

*Some exterior areas keep their essential character and complexity, massive growtg notwithstanding. Here, Pantelimon neighborhood, Bucharest ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Some exterior areas keep their essential character and complexity, massive growtg notwithstanding. Here, Pantelimon neighborhood, Bucharest ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Ferentari neighborhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Ferentari neighborhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Tei Toboc neighborhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Tei Toboc neighborhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Giulești Sârbi neighborhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Giulești Sârbi neighborhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Industriilor neighborhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Industriilor neighborhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

However, a good replacement, in my opinion, is one which is not juxtaposed, but is articulated on the existing fund, a new layer which develops and does not completely deny a logic of living. This is not all about ratios and areas, although, of course, implanting a 6-floor block of flats in neighbourhoods of such demure scale is very brutal; this is also about undertaking certain values – the scale I was speaking of, but also perhaps the transparency of the fabric, the richness of intermediate spaces (even if they are nowadays hidden behind huge, opaque fences), the possibility of keeping genuine gardens.

*Ultra-liberal urbanism in the South of the city

*Ultra-liberal urbanism in the South of the city

For now, I know of absolutely no urbanistic model in this respect. What we have are isolated architectural examples, managing a careful densification at the scale and character of a certain place. It is the case of the house in Bucurestii Noi by the guys at the Republic of Architects, presented in Zeppelin #151, but also of other projects published some time ago in our magazine (and, of course of many which have escaped us).

*Civilized densification. ADN BA: Semi-clllective dwellings, Bucureștii Noi neighborhood. ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Civilized densification. ADN BA: Semi-clllective dwellings, Bucureștii Noi neighborhood. ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Synthesis Architecture: apartment building in the (former) periphery . ©Cosmin Dragomir

*Synthesis Architecture: apartment building in the (former) periphery . ©Cosmin Dragomir

*Atelier Mihai Duțescu: individual dwelling (interpreting the traditional wagon-house typology), Rahova neighborhood

*Atelier Mihai Duțescu: individual dwelling (interpreting the traditional wagon-house typology), Rahova neighborhood

The unavoidable metropolis. Principles for a responsible pragmatism on the outskirts

To continue to allow the periphery of cities to develop under the same logic as they have so far is simply unacceptable. And that is not for aesthetic, ideological, reasons, out of idealism, but simply because we can no longer afford the costs. The collective nightmare consisting of summing up individual dreams will not be limited to the blocking of roads, but will have dark ecological consequences (it already does), and also very severe economic and social ones (see previous articles). The waste of space and resources and blocking future development is unacceptable.

*Industriilor neighbourhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Industriilor neighbourhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

The major issue here is not simply the absence of a strategy and a global policy, but the fact that they seem to be smothered early on. One’s personal and immediate interest prevails over the common, future one. We do not have a solution for this one yet, I dare believe we are also missing an alternative model, or at least a list of acknowledged, shared, and undertaken things.

*Industriilor neighbourhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

*Industriilor neighbourhood ©Andrei Mărgulescu

Let’s not fool ourselves. A coherent and harmonious development of the periphery, guided and controlled through planning, is utopic. The lack of hope of the Romanian suburb seems even stronger if we consider that the periphery of developed European countries itself is getting out of hand, even if things are more civilised, more balanced over there, and development heeds certain rules and is supported by infrastructure.

And yet? Can we at least find a few principles, not just to limit the damage, but also to direct the evolution towards something more decent? A few simple rules and, perhaps, as footnotes, some more complex strategies related to these rules? A reasonable alternative, somewhat applicable to the current phenomenon?

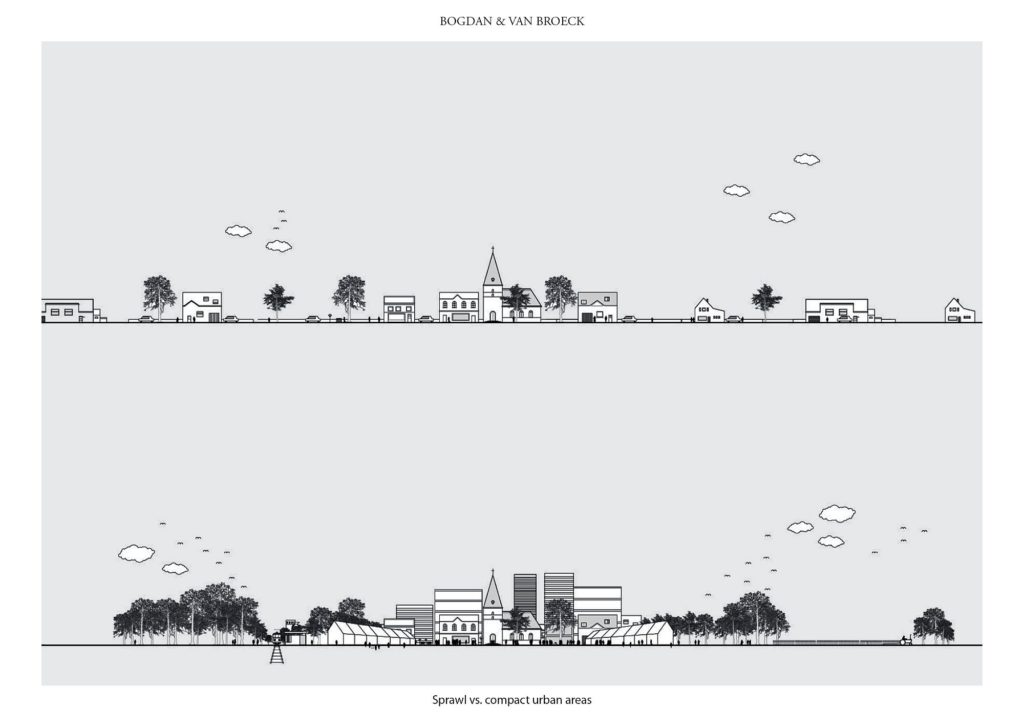

*Model of a new urban policy model in Belgium (see the plan from the introduction to this dossier). Above – present situation of a suburb that covers the whole country; below – a stimulation of retreat, rise in height, freeing land on the plot and aound the settlement, urbanization and re-naturation at the same time

*Model of a new urban policy model in Belgium (see the plan from the introduction to this dossier). Above – present situation of a suburb that covers the whole country; below – a stimulation of retreat, rise in height, freeing land on the plot and aound the settlement, urbanization and re-naturation at the same time

I don’t feel capable of offering an alternative vision. But I think each of us can contribute to building a model, by discussing certain references. Any model needs references and visualization, and, when stuck in contemporaneity and within the local framework, a trip to a completely different type of reality can be of immense help. Thus, let me put the European and current context slightly aside, and I will talk of an ultra-liberal, profoundly pragmatic, and at the same time, visionary, one. I’ll speak about 1811 New York.

Yeah, I know. You dropped the magazine on reading such a ridiculous comparison, such as the one between Manhattan and today’s suburbs, especially the Balkan and Romanian ones. And yet: there as well, even if we find so it hard to imagine, in the neighbourhoods of today’s hundreds of skyscrapers, two hundred years ago there used to be terraced houses or villas, but also, and on most of today’s territory, a nearly savage land, with forests, ponds, hillocks, a few random farms and winding trails. But there was something more there: a firm development principle, and the idea of maintaining vital reserves. The Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 was the one setting up the famous grid. As compared to other American (or colonial) cities, where the orthogonal network was relatively small in extent and then expanded as the city increased, with New York, the stated ambition was to include the development for the following hundreds of years. Even so, they were wrong, as the Manhattan increase would greatly exceed the 8 miles from the edges of the old city, as included in the 1811 plan, while the integration of Brooklyn and Queens was not even on the agenda.

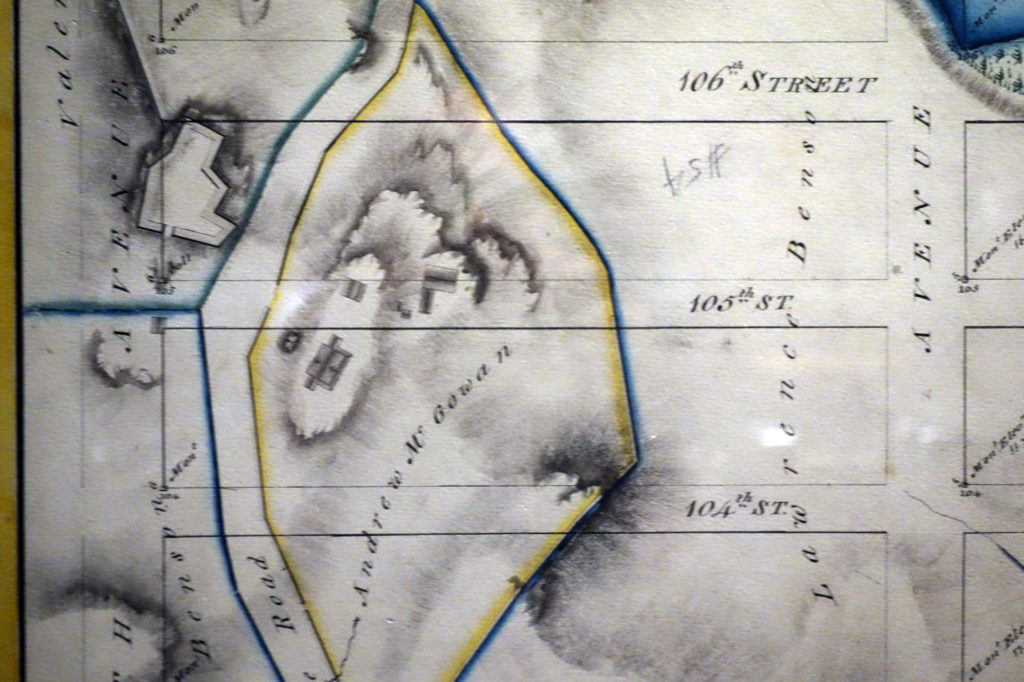

*Randel Farm Map no. 54, detail, 1820. Overlay of the planned new system of regularly gridded streets on the actual terrain. Image from the permanent exhibition of the Museum of the City of New York

*Randel Farm Map no. 54, detail, 1820. Overlay of the planned new system of regularly gridded streets on the actual terrain. Image from the permanent exhibition of the Museum of the City of New York

Well, even so, this grid stayed virtual for some time. A projective map, overlapping a rural territory. But it set the city’s bone structure, so to speak, its infrastructure of roads, equipment, and public spaces, and has largely remained the same to this day, when everything else has changed. It has incorporated things no one back then even dreamed of – an immense densification, the subway and the cars, and pretty much all the nations in the world brought together.

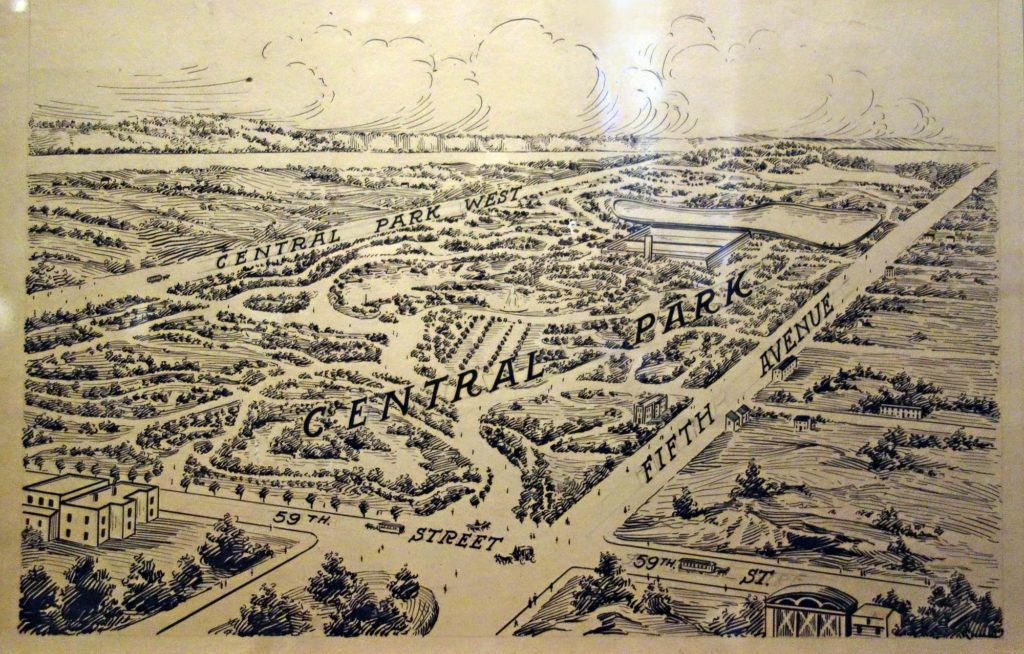

After very few decades since the establishment of the grid, the second iconic element of the city appeared – the Central Park. But in the beginning this was just a reserved land itself, dedicated to be forever used as a public garden, and taken out of the real estate market. Just look at the small and funny aerial perspective of the park in its first years: a few houses, clearings and trees, where today we have built canyons or the Guggenheim Museum. But today’s streets and the park were already there.

*Central Park, Founded 1857. Image from the permanent exhibition of the Museum of the City of New York

*Central Park, Founded 1857. Image from the permanent exhibition of the Museum of the City of New York

I hope you don’t believe I am asking you to imagine a New York in the greater Bucharest area? A vision of a grid for the 21st -23rd centuries? No, of course not. Nothing formal, nothing geometrical. But I would dream of a responsible-pragmatic strategy for minimal, yet efficient, hardware, able to develop and for the establishment of an urban reserve.

We can have no idea about what and how the suburbs will evolve. From villages and agricultural plots, we are now down to villas, then gated comunities, then blocks of flats, but also, in a completely unexpected way, office developments and a lot of other places. In some way, we have, in the northern periphery of Bucharest, very dense areas, and a richness of functions – elements of a city, yet devoid of interworking, of public space, of the hierarchies and rules of a city. However, natural, agricultural, or simply very poorly built and equipped areas still survive.

As we can control almost nothing, and (yet) do almost nothing of public value, we can attempt, at this point to define the essential places to save and keep. For instance, forests taken completely off the development circuit, stopping any functional change; but also areas for expanding these green fragments; establishing the fields, of the still public ones, on which we should refrain from building – a space reserve for the future; encouraging densification, which will happen, anyway, but perhaps allowing a vertical increase, provided that free spaces be maintained on the respective land. Keeping would go hand in hand with the traffic and infrastructure hardware I was speaking of earlier. Of course, the comparison to New York, and, in fact, to any historical expansion, really seems to die out here, for there is pretty much no virgin land left; any infrastructure needs to find a place within the existing grid or to develop the latter. Even so, any new street can be created in a more generous manner, from the start, with sizes that should allow an urban character, with wide sidewalks, bicycle paths, rows of trees and other green spaces. Even if now it is in the middle of a field. It can be thought as an element of a future urban tissue, not just as a technical solution. That it would, most certainly, generate a much more intense development on its margins, but a truly urban one. Perhaps, even in the chaos of today, one can request and get the investors’ support, not for setting out perches, as in the historical metropolises, but at least for lining buildings down the road and for public ground floors.

Just a few simple rules. There will probably never be harmony in these areas. But we may have the chance to get some order and a few qualities to make living better, and to allow the appearance of a hint of urbanity. And, from a wider perspective, the compact city, density coupled with open and green spaces, but also with more hidden parts, less or otherwise developed, represent, as the European urbanists have already realised, an ecological action which is much more profound and efficient than any treatments and equipment applied to the buildings themselves.

Periphery has its own chances.