Introduction

Text: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

As you probably know, the “Roșia Montană” natural and cultural site was included on this year’s UNESCO’s World Heritage list. This is, of course, a tremendous joy, the result of fierce battle which was fought, in varying proportions, by hundreds of thousands.

But this is not what I want to talk about here, but about what I learned, while reading this year’s list and then a few from the past few years.

Thus, among monuments and sites, sometimes thousands of years old, I also found a place I used to cherish and visit as a student, the Mathildenhöhe complex in Darmstadt, an artists’ colony and a peak of the German Sezession style; then, closer to us, the works of Jože Plečnik in Ljubljana, an acknowledgement of the exceptional value of an un-rateable modern architect. Farther away, but closer in time, there is also a Mexican engineer on the list. Since the 1950s, Eladio Dieste has built such delicate brick-vaulted buildings, that they seem made of paper. In fact – architects, watch out! – this year’s list is full of engineers, because hydrotechnical works have also been included: the “Dutch Water Defence Lines” – the grand programme, over 200 km in length, which took place between 1815 and 1940, or the interwar Trans-Iran railroad. Therefore, at least 5 out of the total 34 included sites.

So that countries and assessors should not be suddenly seen as falling prey to Modernism-mania, it is worth looking back. 2016 saw the addition of the Pampulha Brazilian complex (Oscar Niemeyer, alongside many artists), and Corbusier’s work. It was Frank Lloyd Wright’s turn in 2019. And, over the past decades, there have been isolated Modernist works.

What do I mean by that? I will definitely not go down the path of the frustrated nationalist delirium on our eternally being wronged. Although, let’s face it, the fact that Brâncuși’s ensemble is not included is disgraceful. It is also an issue related to its agenda – a war memorial is difficult to include on a UNESCO list. But the disgrace is also ours, given the complex of internal causes, from the lack of competency to the general lack of care.

Let’s get over Brâncuși and let’s talk of Romanian Modernism. Perhaps, no matter how proud we architects and culture folk were of it, this movement’s works do not necessarily comply with the criteria for such a classification. But, if the UNESCO list is a sort of crème de la crème, a world-class acknowledgement (and not a support for salvation), the vast majority of candidate sites are already protected on a national level.

How are we doing in terms of Modernism and heralds of Modernism within the current Romanian territory? We are doing very poorly indeed. It’s true, first the Neo-Romanian and the Hungarian Sezession, but also a horde of other interwar Modernist buildings, are on the heritage list. But this does not also mean we are taking care of them. Go for a walk down Magheru and have a look at our interwar icons and the state in which they have been brought, never mind the huge risk of their falling down with the next earthquake.

*arch. Horia Creangă, „Patria” Building, Bucharest

As for post-war Modernism, the `Communist` one, with that even official acknowledgement is completely absent. Cătălina Frâncu and those with whom she talked explain this in our file, which we have largely dedicated to an overview of modern history.

In Romania, the restoration of Modernism is nearly absent. We start our Dossier of Zeppelin no. 163 (autumn edition) by such an example – a small apartment building on bd. Mărășești. It becomes the end of a new apartment building and is lovingly brought back to life by the Starh team.

In fact, this collective housing project introduces the materials in the file which do not deal with Modernist heritage per se, but with carrying on classic modernity. They show, we believe, that Modernism is not just a matter of fashion and style, but also of architectural principles and spatial rules.

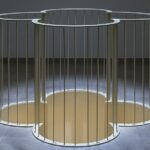

It is the case of the two ADN BA projects, a large insertion in the Bucharest historical centre, and a model-house on the outskirts, a study of the Raumplan and of structure as a determinant of space. It is the same approach we had with the Unfolding Pavilion, an independent work within the Venice Architecture Biennale, which starts from a theoretical project by John Hejduk and brings together the history of the trade and contemporary art.

We end our dossier with an example of international best practice, from an European area whose countries all find a strong element of national identity in their local classical Modernity. We did not search for a world-famous work or architect, but a good quality post-war social housing complex, yet even comparable with what we have. Light years away from our pitiful “thermal rehabilitation” program, the restoration in Helsinki is exemplary from all points of view.