Text: Mugur Grosu

Foto: Mihnea Ratte, Cătălin Georgescu, Marina Popa, Corina Cimpoieru

Here’s a stereotype to wonder about: “A Romanian is born as a poet”. The brimstone in our cities bears, nevertheless, testimony to the contrary: not only is there no place for poetry in them, but one can hardly find some place for people as well. Nothing stands before the new gods—the car and the money; to research them is blasphemy, to challenge them—apostasy. Then again, why grumble: there is also a bit of poetry. In Constanta, for instance, my home city, built upon the citadel made famous by exiled Ovid, a monument to the unknown sailor turned up a decade ago, showing off a boat propeller and the text: “Free man, you will always love the sea”—a more relaxed translation of the first line of Baudelaire’s Man and the Sea. That’s all they could. Ironically enough, the monument’s “benefactors” are now nearly all locked up or searched for by the Interpol. We’re doing a bit better in Bucharest. First of all, we have two dedicated streets: Poetului (Poet’s Street)—in Bucureștii Noi, and Poeziei (Poetry Street), between the Colentina depot and Târnăcopului (Pickaxe street). If we were to trust the map, the poetry and the pickaxe rank the same here. Nonsense. But in Kiseleff Park, we are really lavish: on the plinth of Omar Khayyam’s statue, we can read a few Persian quatrains—called Rubaiyat. And last year, we were on the edge of overdosing on poetry: the Street Delivery event was dedicated to “Poetry on the Street”. And I was happy to participate, with two poetry installations—a street puzzle game with poems calligraphed on ceramic tiles, and a suspended installation in the Anglican Church Plaza—“Gone Poets’ High Society”, through which, for a few days, the plaza was animated by poems.

This year, pandemic-imposed recalibrations took Street Delivery out of downtown, activating, instead, many city islands. I was surprised when organizers still invited me to design a continuation of last year’s installation, maybe something lasting. For the second year in a row, the space around the Anglican Church would symbolically become the “Gone Poets’ Plaza”. Following the first visits to the space, we got a sliver of an idea, for which we also enrolled Justin Baroncea, who was due to return from Barcelona. It would have been fun, but the plan fell through, as Justin was required to self-isolate at home. Maybe next year. I went back on site, forced to think of something else, something simpler. While hanging around in the plaza, I remembered the triggers animating Street Delivery in the beginnings: a Zonal Urbanistic Plan—“Cultural track Episcopiei Street, Pictor Verona Street, Grădina Icoanei”—created under the coordination of Șerban Sturdza, apparently assumed by the city leaders, but forever blocked in permit-issuing stage. In 2009, a small segment of the plan was given the green light—the rehabilitation of the Anglican Church Plaza, but lacking an essential element: making the Verona Street pedestrian between Grădina Icoanei and the Casa Universitarilor Park. The plaza is, basically, a small island snatched away from the cars—in a bayonet fight, highlighted by the bollards surrounding it. (That, while increasingly more cities around the world are doing away with street curbs altogether, to remind drivers that they are only guests there).

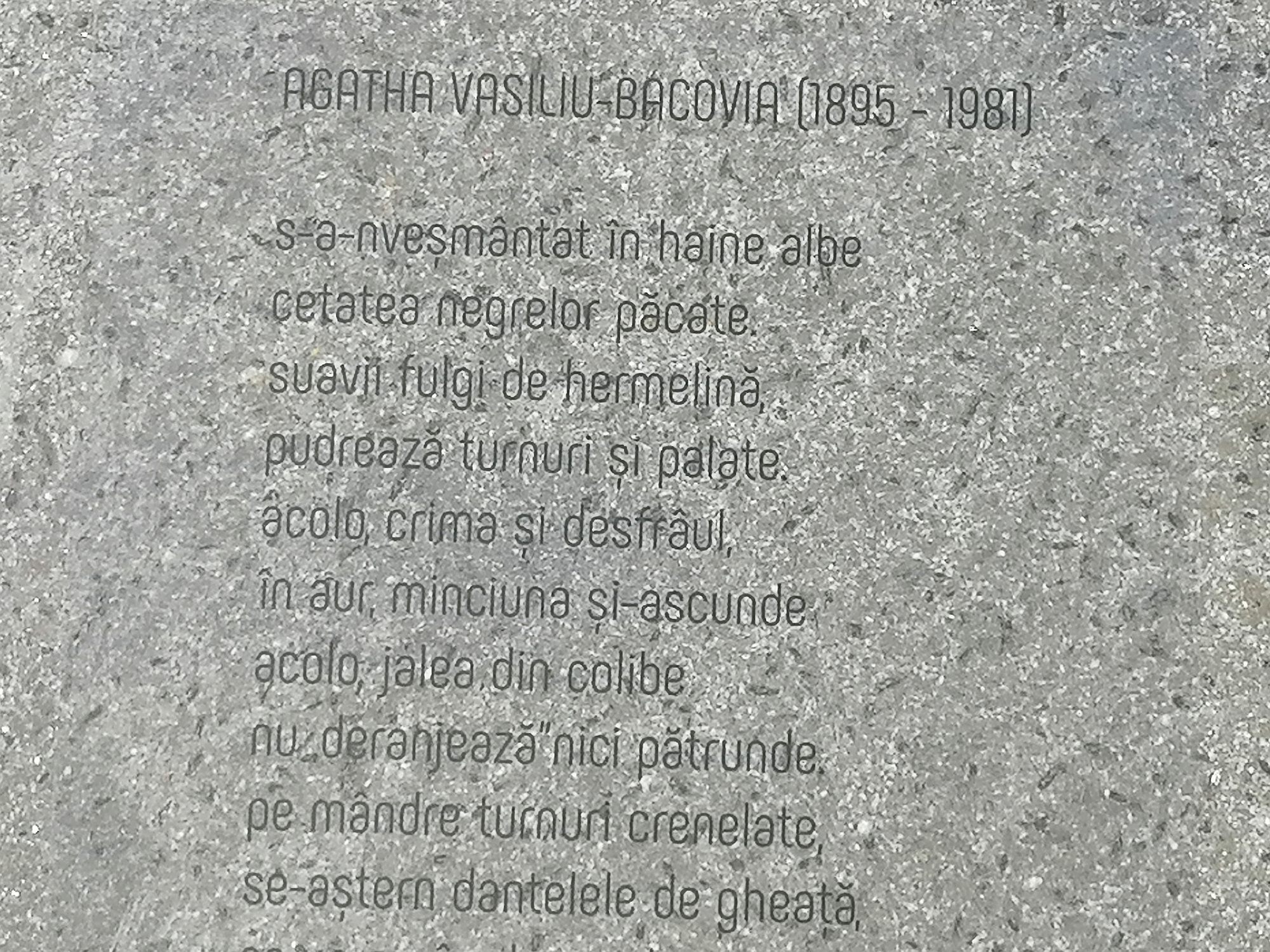

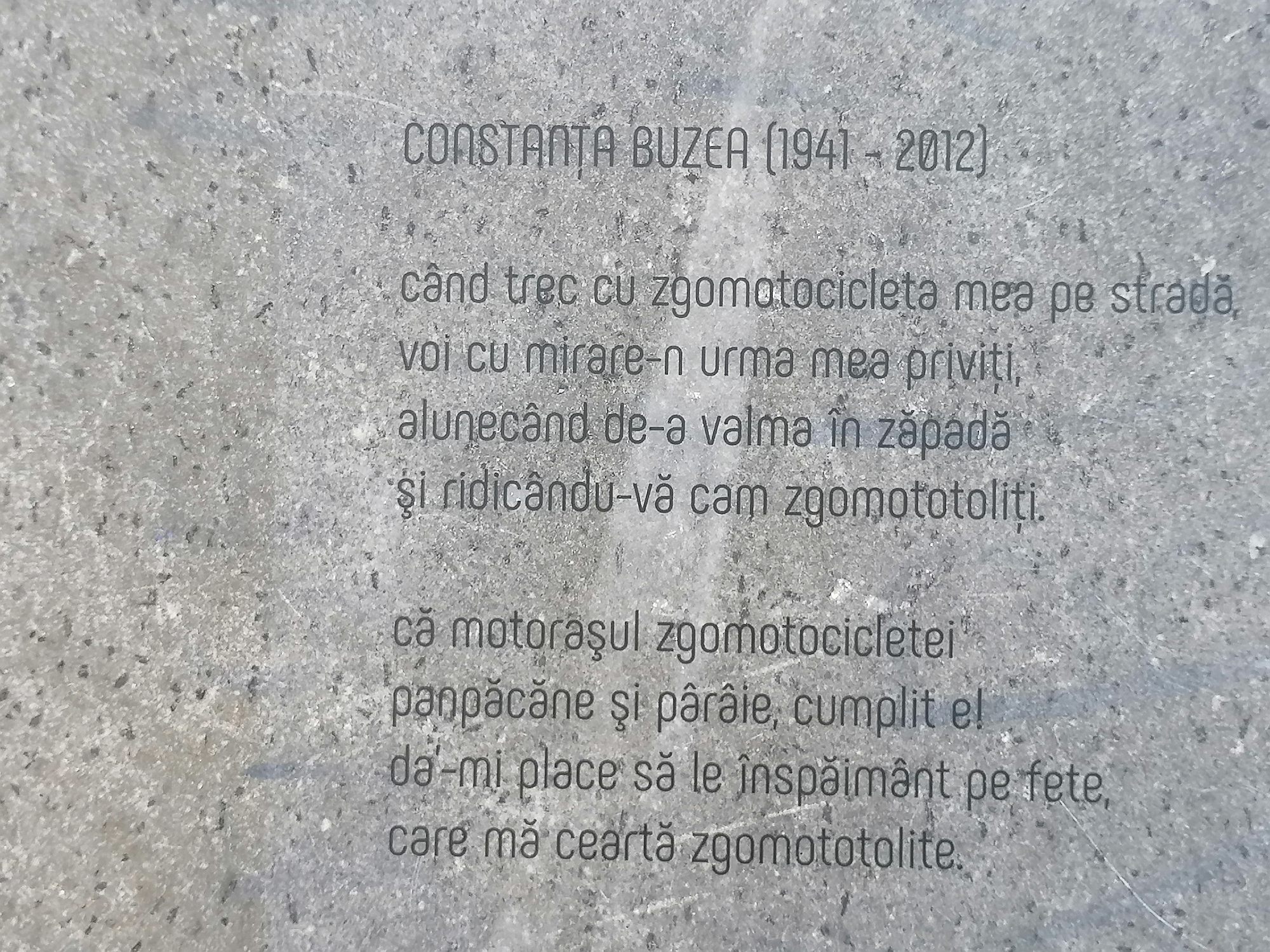

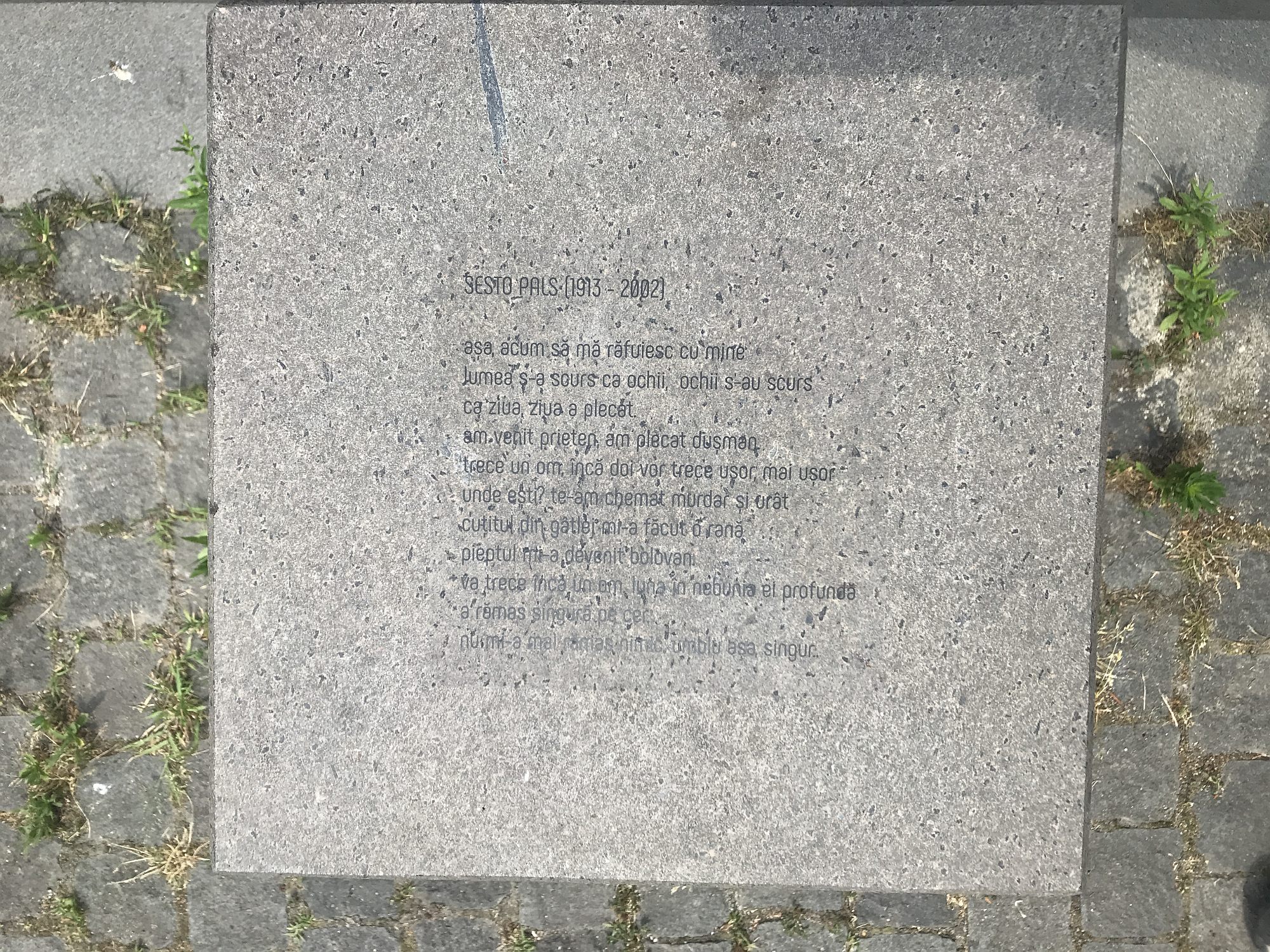

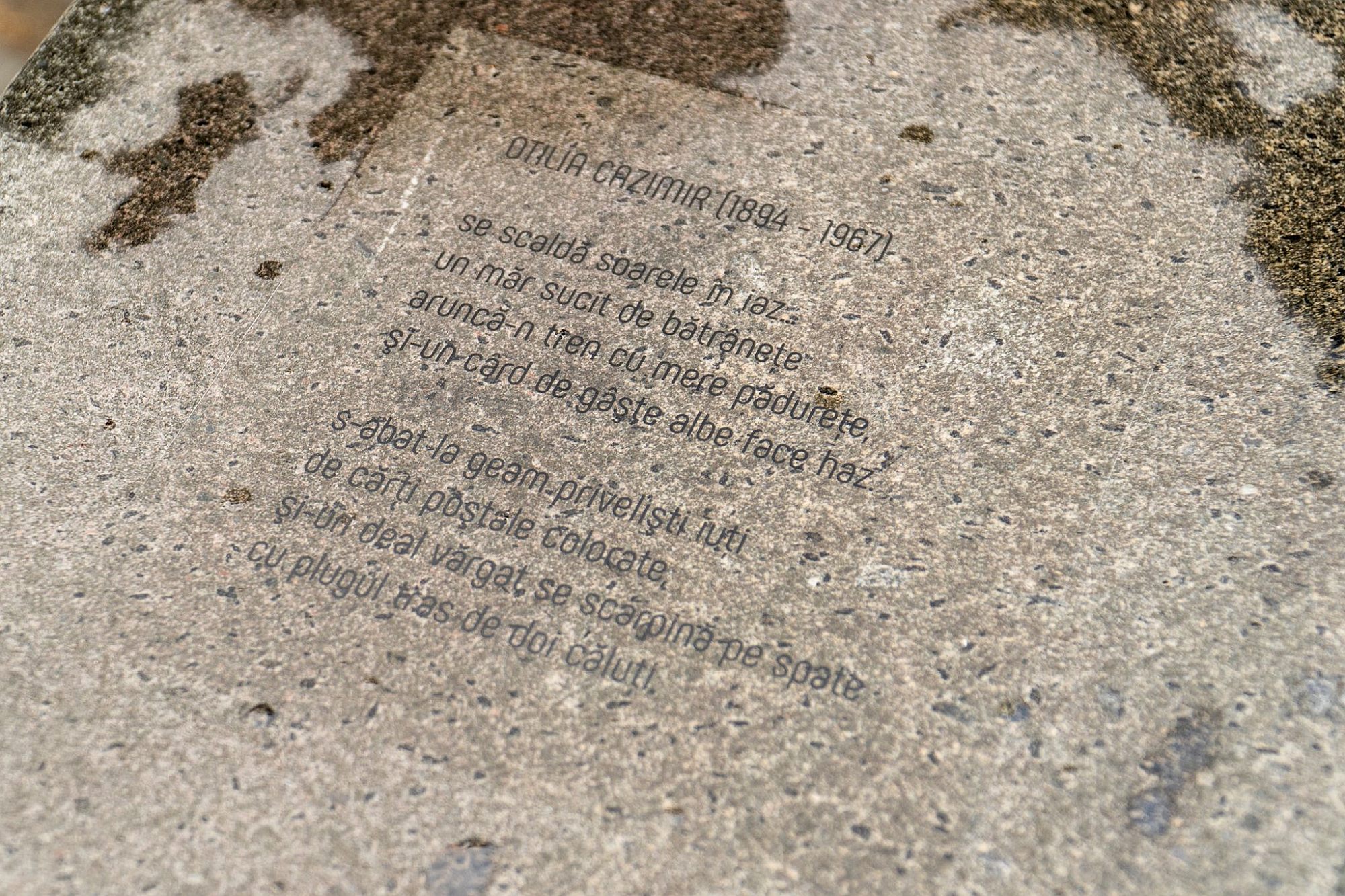

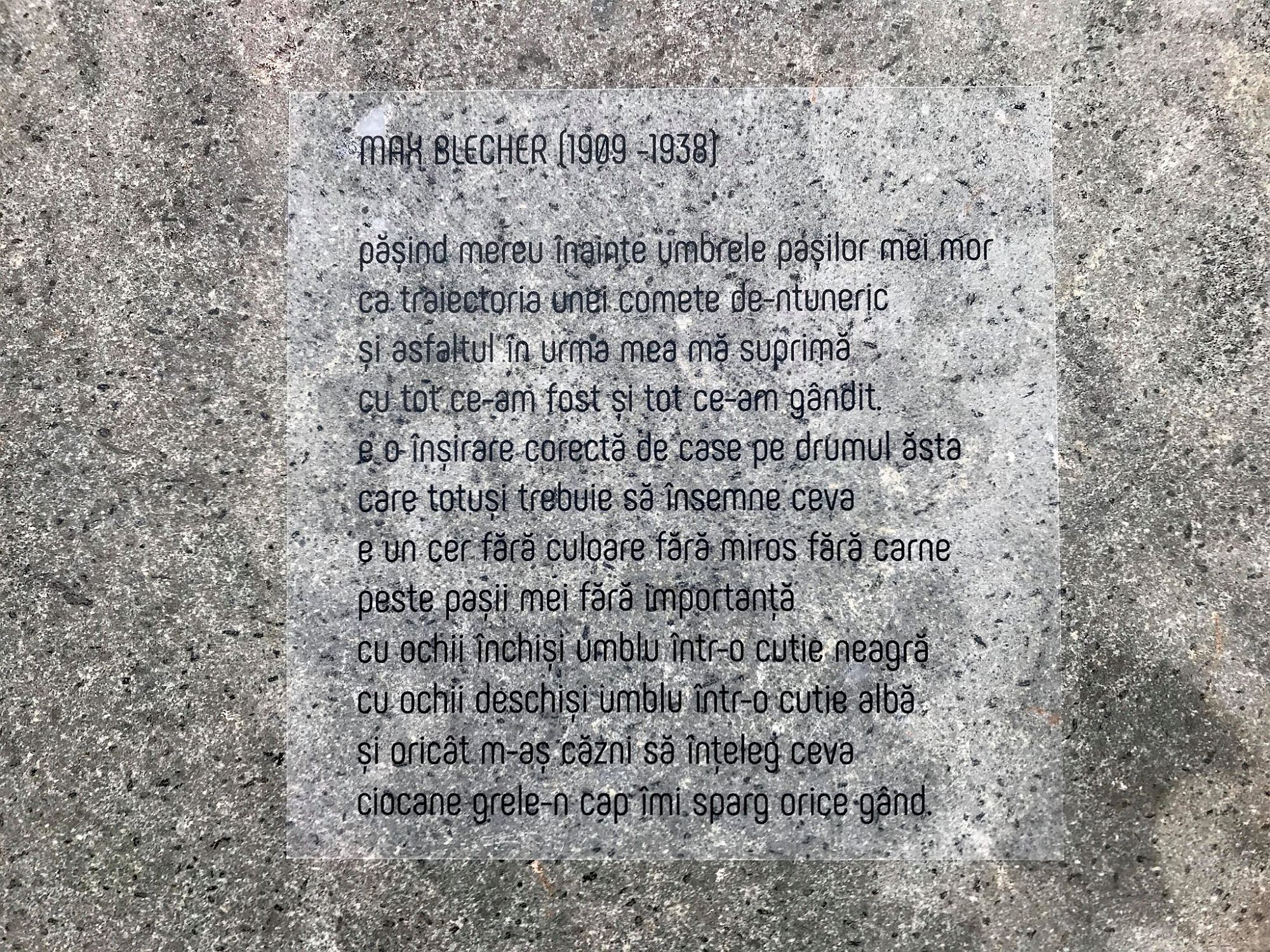

Although only meant to block out cars, the rhythmic sobriety of their granite presence was suggestive of the cloaking of this antagonism and their symbolic turning from the street to the plaza: if I cleaned their upper side of paint vandalism and stuck a matte, transparent sticker on each of them, with the poem of a gone poet, I would be composing a discreet, low-cost memorial, dedicated to gone poets—not only gone away, but also gradually gone from our memory; minus the “textbook” and Baccalaureate exam poets, therefore. A nearly forgotten poet on each bollard. And many women poets—little known or evoked only by association to iconic male “textbook” poets. Claudia Millian Minulescu, Agatha Vasiliu-Bacovia, Iulia Hașdeu, Maria Banușor, yes, Veronica Micle—with a really modern “reply” to Eminescu’s Luceafărul. Or historical avant-garde poets, usually sparsely evoked, as a group. I was equally captivated by the beautiful part of selection, and by the dirty job of wrecking my hands in solvents, of rubbing off and neutralizing the various types of paints collected over the years. And the small repairs, such as the replanting of a pillar overturned by a car.

*small repairs (before & after)

I am grateful to Corina Cimpoieru and Alexandra Dincă for the “clean copy” of the 74 texts: their minuteness has made the intervention even more discreet.

If you walk quickly through the plaza, you may not even notice the change, so I also received admonitions for excessive… discretion, or because texts are difficult to read. I must confess, I felt it was more important for me to convey the feeling of imminent disappearance, of texts fading away under your eyes, rather than inviting people to read. And I wanted the readers to, involuntarily, make a small curtsy before each poet they stop to read.