Edito: Dystopia is not (only) our fault

Text, photo: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

DOSSIER: „My house, our house”

Negotiating dwelings in times of crisis

Dossier coordinators: Ștefan Ghenciulescu, Cătălina Frâncu, Ilinca Pop

We don’t have enough housing. But we are also running out of land or money.

Of course, it is difficult to find any moment over the past 200 years when one could not speak of a habitation crisis: More intense or rather demure, localised following rapid development or disasters or a generalised one, the housing crisis has been with us all along. What seems to have disappeared, in stark contrast with the postwar period and the 1960s, is the State’s involvement in building housing. Of course, the massive boom has also brought along a host of mistakes and issues – ghettoization on public money, social and urbanistic catastrophes etc. But, over the last 50 years, the authority steps back, leaving a free reign to the more or less regulated market. The phenomenon can be sudden, as is the case of former Socialist countries, or more moderate and slower in the more developed countries.

No matter how much of an economic liberal and anti-public interventionism supporter you were, you’ll have to admit that the exponential increase of needs, the lack of quality for the majority of new developments, and also the climate crisis and the need to preserve some unbuilt territories are imposing a new urban contract. There’s a major need for an acceptance of regulations, a more democratic urbanism, a veritable and complex ecological thinking, accessibility, collaboration instead of unprofitable individualism etc. (…)

Brick social housing insulated with seaweed

08014 arquitectura: 24 apartments in Ibiza

Text: Cătălina Frâncu

Photo: Pol Viladoms

Social housing doesn’t have to be boring or look cheap. In some cases, social housing differs slightly from ‘for sale’ housing in its finishes — especially those built in the 80s and 90s, when the same shape was built with stone and exposed brick on one side and PVC on the other. Not the case here. Since starhitecture is questioned more widely than socialist circles as a waste of resources, social housing continues its rise as an area of experimentation and an example of good practice.

08014 arquitectura is building a semi-community block with 24 social housing units in Ibiza. The small dimensions and the efficiency of the spatial transition place the block between individual and collective housing, in a simple spatial gradation: the private apartments are contained in a clear structure, double-oriented around atria with a double function: air conditioning and lighting. The pathway to them is lit, generously sized and flexible enough to be appropriated with various shared functions.

The apartments are owned by the Balearic Government, which makes them available to those below a set income threshold, and the rental price is between €350 and €500 per month. (…)

PARIS. LIVING. 2023.

Text, photo: Ștefan Tuchilă

(…) Large urban centres in France, Paris especially, are areas where people are living their lives outside their homes. Paris, at least, has a nearly Mediterranean lifestyle, despite the fact that the weather has nothing to do with what happens far south. Besides other economic, cultural or social factors, this is the motivation that convinces Paris inhabitants to live in very tight confines (the average housing area is 58 m2, and the average useful area for one inhabitant is 25 m2), in Europe’s densest metropolis (somewhere around 21,000 inhabitants/km2).

The quarantine triggered by the Covid epidemic drastically changed priorities, and many have started to wonder about the few months spent under lockdown in their suffocating apartments, without access to the public space which usually worked as an extension of the private space. The exterior space (balcony, loggia, terrace) has become a priority, and this tendency was almost instantaneously translated into programs for new housings or the priorities of real estate agencies. At the moment, many of the standard programs for collective housing operations start from the presumption that all housings have an exterior space. (…)

The Building as a (Future) City

Bruther + Baukunst: Student housing and reversible carpark, Saclay Campus

Text: Cătălina Frâncu, Bruther

Photo: Bruther @ Maxime Delvaux; Bruther @ Filip Dujardin

The car has remade our cities and ourselves. As we cannot discard it completely right now, what if we could design its spaces so that they could in time become something else?

In the closer South of Paris lie smaller towns with specific communities, such as university campuses. There is still room for large-scale experiments there, such as this collaboration between Bruther (Stéphanie Bru and Alexandre Theriot) and the Belgian office Baukunst (Adrien Verschuere). The raw and heroic building is a contemporary take on the ideals and language of historic Brutalism, but also a reflection on order and diversity, domesticity and domestication of infrastructure. A smart and poetic way forward.

15 Heap Apartments inside of an Urban Island

HHF. Landskronhof in Basel, Switzerland

Text: HHF

Intro: Cătălina Frâncu

Photo: Laurian Ghinițoiu, Maris Mezulis

Landskronhof is the answer to Basel’s need for densification. Almost derelict, irrelevant urban areas (as more than parking spaces within the urban islands) are slowly becoming attractive for new construction. In the urban fabric, architects build an object that responds to the need for densification, illumination, gradual transition spaces and community. The community is understood in this instance as comprised of the inhabitants of the 15 apartments, but also the small animals and insects that can shelter in the surrounding vegetation. Remarkably, not a patch of lawn can be glimpsed in any of the photographs. I’ll explain, because at least in Romania, we are fighting a hard battle against this barren monoculture with which we stubbornly keep away bees, hedgehogs and other insects and animals that have the ability to increase our quality of life (or even save it): lawns are a status symbol; the English used them to show that they could afford to use a large lot of land for aesthetics and not for any kind of production — back then they were few and far between (lords and the like), but today, almost every backyard home has a lawn manicured with a gas mower. Meanwhile, tourists from England come to us to see the wildflowers, which they don’t have anymore.

It seems the new directions are becoming increasingly clear: terraces on low-rise high-density blocks with the potential to create green and biodiverse spaces on a human scale, a mound of people and plants in contrast to the concrete and PVC fortresses of the last century.

Density and delight

Shift architecture urbanism: Domūs Houthaven apartment complex, Amsterdam

Interview: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Foto: René de Wit, Pim Top

How can more people still afford to live – and in a good way – in the city? This project shows one way to do this, from within the market, but in a responsible way. Ștefan Ghenciulescu talked to Oana Radeș and Harm Timmermans from Shift. There came up social trends and money, urban hybrids, real common spaces and the 21st century alcove bed.

Missed Opportunity: The National Housing Strategy 2022-2050

Why do architects need government strategies?

Text: Cătălina Frâncu, Teodora Vătavu, Liliana Oprea, Andreea Ghenu

Photo: Cătălina Frâncu

(…) The National Housing Strategy (NHS) has gigantic potential to influence future policy directions. Vienna, a city with more than 60% social housing stock, has succeeded in building a sustainable economic ecosystem in which every actor involved in housing development functions: from developers to architects and developers. The eligibility threshold for social housing is low enough for 75% of the city’s population to qualify, and the minimum requirement for a first application is to have lived in Vienna for 2 years. The regulations for the development of social housing require, among other things, that both the location and the finishings are similar to those for free-market housing — while maintaining both housing standards and the quality of the built environment. Spatial segregation on socio-economic grounds — one of the indicators of social stratification — is absent due to the homogeneous intermixing of social and open market housing throughout the city.

It would have been ideal for romanian Strategy to propose, in principle, a regulation similar to the one in Vienna, aimed at ensuring high and uniformly distributed architectural and urban planning standards both spatially and socially. (…)

The market is not the solution, but the cause of the housing crisis — some thoughts from Cluj

Text: Enikő Vincze

Photo: Căși Sociale ACUM și George Iulian Zamfir

(…) To describe very briefly the housing crisis in Cluj, it is to be mentioned that, between 2015-2019, 15,587 homes were completed in the city, all from private funds. No social housing was built by the municipality during this period. In 2015, the average price per square meter in Cluj-Napoca was 956 euros, and in 2019 it increased to 1590 euros/sqm. The increase continued in the following years, so that in May 2023 it reached 2450 euros/sqm. Between 2015-2019, the number of people living in the city with domicile (official address noted in ID cards) only increased by 3420. We can therefore ask, rhetorically, where the high demand for housing in the city of Cluj comes from, if not from those who settle here? Who can pay the ever-increasing housing prices (to rent or buy)? In parallel, an equally important question is why aren’t more applications for social housing? Why has the idea stuck, not only in the minds of real estate developers and public authorities, but also among the population entitled to social housing (with incomes below the national average and without owning a home), according to which the market must and can respond to the housing needs of people? Many people live in Cluj-Napoca on rent without having a lease agreement with the owners. According to some unofficial estimates, the percentage of private renters in the city is 15%. Many of them, not having their domicile registered in Cluj-Napoca, are not eligible for social housing. Moreover, more and more housing units are being completed and traded on the market in this city for investment purposes. Because the city is promoted as a location worth investing in, while more and more young people at the beginning of their careers or older people are forced to leave precisely because they do not have enough income to pay the high housing costs.

Housing vulnerability

……And something about Romania’s National Housing Agency

Text, photos: Anca Dumitrache

The term housing crisis defines a period of time during which affordable housing units become more and more scarce in proportion to the number of people needing them. This phenomenon is spread across many countries in the Western world, causing many people to be affected by housing vulnerability. In the United States people earning the minimum wage cannot afford the rent of a two-bedroom apartment in any of the 50 states, while only being able to afford a one-bedroom apartment in 7% of all counties (NLIHC, 2022). In Europe, the situation is more balanced, but the price of housing units is experiencing an upward movement. 8.3% of the EU population have housing expenses that exceed 40% of their monthly income (Eurostat, 2021). At a European level, Romania is one of the countries with a low degree of housing vulnerability (Eurostat, 2022), but with a high level of housing overcrowding: 41% of people live in overcrowded households (Eurostat, 2021).

“Predictability is the best thing you can offer.”

A conversation with Georgian Marcu about current Bucharest developments

Interview by Ilinca Pop

Georgian Marcu has been working in the residential segment of the Romanian real estate market for over 17 years, having an eye on the dynamics of developments “from the ground up”. He says the percentage of rejections in his profession is only surpassed by the performing arts: an agent is told “no” only slightly less often than an actor, which puts many in the position to give up quite quickly. Five years after the Romanian real estate market “coming of age”, we are faced with a post-pandemic change in housing culture, inflation, rising interest rates and blocked developments in the downtown area of Bucharest. However, the city continues to attract a consistent demand for housing. Do we have reason to be optimistic?

Scale-intersection urbanity

ADN BA. Marmura, infrastructure for community and dwelling

Text: Cătălina Frâncu

Photo: Vlad Pătru

Weaving an unstructured urban fabric is the cusp between architecture and urbanism. We know ADNBA best from the city centre, where they have been designing urban fillings, blocks of 20 apartments in coherent urban grids — but even their small scale projects take into consideration urban principles. In this case, however, they make a gesture that structures the urban scale. Near the intersection of Șoseaua Chitilei and Bulevardul Bucureștii Noi, remains an unscraped triangle from the Bazilescu allotment, between the many former factories in the area. Here stands Marmura Residence, an atypical development for Bucharest, but especially for the area, which morphologically echoes the 1960s blocks in the vicinity of the park.

Romania’s De-Citifying Transformations

Vasile Ernu interviews Sociologists Norbert Petrovici and Florin Poenaru

VE: The latest census has brought a multitude of new data, even new phenomena. One of these phenomena is showing us that our cities are decreasing. You wrote an analysis on Romania’s `de-citifying`. Where did you start this analysis, and how? In sociology, we have terms such as peri-urbanization or rurbanization. You have studied these phenomena. What is the difference between them and what you call `de-citifying`, and is this different from the urban ruralisation phenomenon?

NP/FP: The Preliminary data of the Census of Population and Housing (RPL 2021) in Romania is indeed showing the deepening of a phenomenon that started over a decade ago: the country’s peri-urbanization1. While the number of city inhabitants is decreasing (we are mainly concerned with county capitals), the number of inhabitants in their adjacent communes (and, in some cases, towns), is increasing. This is a country-wide phenomenon, but a few examples are paradigmatic, such as Bucharest’s peri-urban area, where the population has increased by over 150,000 inhabitants over the last 10 years. (…)

About (Middle Class) Living in Bucharest, Today

Ilinca Pop & Bogdan Iancu: In and Around the City. A Conversation

Bogdan Iancu is an anthropologist, lecturer at SNSPA (National University of Political Studies and Public Administration) and researcher in many projects focusing on cities and urban communities. Between 2015 and 2017 he was part of a research project on the material culture of the middle class in Romania, in which he specifically followed the locative (material culture, architecture) and spatial aspirations of middle-class representatives. We discussed what has changed since the project ended and why, who, where and how is gentrification produced in Bucharest and the perspectives from which the urban policies approved in Romania in 2022 could be viewed. (…)

Exoskeleton and lived-in courtyard

Attila Kim Architects: House with exposed concrete, Bucharest

Text: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Photo: Vlad Pătru

We are in one of the former semi-rural areas in northern Bucharest, where most all old houses have made way for post-Socialist villas (especially since the 1990s). The new constructions, with a few exceptions, do not possess any architectural value. But they generally observe the model of the house with a yard, it’s true, a house with two levels, sometimes with an extra attic. The neighbourhood uglier, is more crammed and more chaotic than it used to be but, as there aren’t so many apartment buildings, there still is plenty of greenery, and the general scale remains decent and pleasant.

If you hurry by, you won’t even notice that the plot at 6, Dărmănești St. has received a permanent construction. Recessed from the street, with only one level and a sort of transparent gazebos on top, with exposed concrete facades and grey plastering, the house, built for a family of two parents and two children, is barely rises over the semi-transparent fence. (…)

The house that sings and The house that listens

Two houses and their stories

Projects, texts: DAAA

As an architect, there are many instances when you end up working for years on one and the same work. But it is not so often that you happen to resume, at a later moment, working on a place or finished job. It is the case of these small-scale densifications, both entailing something more than actual living.

Restoration without a drawing board

Rehabilitation and landscaping interventions on the homestead in Urluiești, Argeș

Photo: Raluca Munteanu, Horia Stănescu

A vernacular homestead, made, repaired, altered and adapted over time to the needs of its inhabitants: it is difficult to set on paper/screen and to design a proper project for it, according to current standards. It could be seen as a restoration, in the sense of returning the building to its moment of glory. Nevertheless, the project itself is in fact an extensive effort of repairing and harmonizing techniques, in order to correct the issues accumulated by improper alterations and uses.

Low-key order

Vinklu: The MDP House (Bisericani, Neamt County)

Text: Ștefan Păvăluță

Foto: Vlad Albu

This little house hides a host of surprises: a modulated plan over an implacable square grid, a succession of very different spaces, a dance between traditional, classical, and Modernist-inspired elements. The photographs show that total design is not amust, and that quality spaces can be inhabited nicely after the architect has left

5 x 2

cra-de.studio: TRSA HOUSE, Mogoșoaia

Text: Jean Craiu, Ada Demetriu

Photo: Sabin Prodan

The house in Mogoșoaia lies is in an average-density, mainly residential area, with low-rise individual houses. The rectangular plot, its short sides to the north and south, is situated between the Mogoșoaia forest and lake, neighbouring the sports complex of the same name.

ZOOM

Cities That Transform – Beirut after the Blast

VICEVERSA: En exhibition in the Basement of the Palace of Parliament, Bucharest

Text: Laurian Ghinițoiu, Dorin Ștefan Adam

Photo: Laurian Ghinițoiu

Cities are transforming at a rapid pace nowadays, but changes are never random. Factors of various historical, political, economic or social periods are influencing not just the built environment, but also our societies. The process can be a long-term one, carried out over hundreds of years or, on the contrary, instantaneous. Understanding the nuanced context and current memory is part of the effort of the “Orașe în transformare – Beirut după explozie” (Cities That Transform – Beirut after the Blast) project.

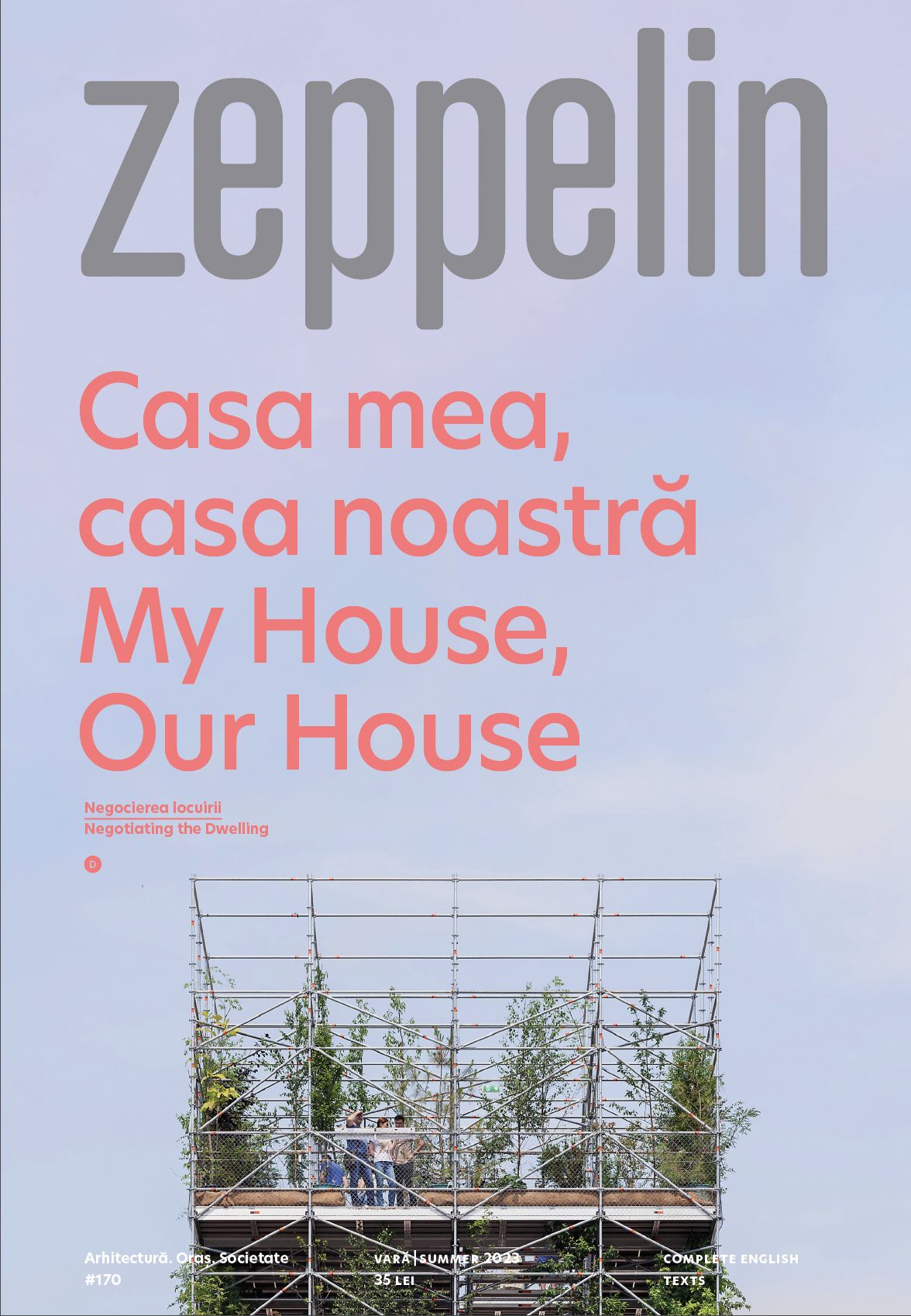

The Nursery.

1306 plants for Timisoara

Interviews: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

In 2023, Timisoara is a European Capital of Culture. The program is based on several components, one of which is the section Places relating to the city’s spaces – old and new, to urban regeneration and discussions about the city’s future. One of the main interventions of the European Capital program is the Nursery – a provisional tower located in the space with the greatest symbolic importance in Timisoara. The project due to a collaboration with the or5der of Romanian Architects – Timis Territorial Branch, is spectacular and has become one of the European Capital’s symbols. While it became an instant icon, it is not one of the strong, yet meaningless objects we see so often today, but an instrument for debate and urban transformation. I have talked about its purpose and importance, and also about the sometimes-harsh reactions it caused, with representatives of the team that made it possible: Cosmina Goagea (Timisoara 2023 curator – the “Places” Territory), Alexandra Trofin (OAR Timis), MAIO Architects, Barcelona), Alexandru Ciobotă, Raluca Rusu (Studio Peisaj, Timisoara).

PLANS