Text, photo: Mugur Grosu

On the TV screen on top of a beat‑up metallic oven, a shamelessly familiar image from the civilised world: British adventurer Bear Grylls showcases one of his famous essential techniques of survival in the wild. I have no clue what he’s talking about, as the sound is cut off and the subtitle is in Arabic. Nobody in the room is truly interested, the image is left to flow on the screen as a background, as a sort of modern wall carpet of the Western mirage instead of the old style Oriental scenery.

That’s for the best, as it would be difficult to explain, here of all places, our fascination with such scenarios, of self‑abducting oneself to the middle of nowhere. A flame flickers on screen, rising merrily and illuminating Grylls’ face, who has, of course, proven yet once again a new technique of making fire with bare hands. An image that will keep haunting me: the fire on TV, over the oven connected to a gas cylinder that has probably not been filled in a very long time. Otherwise the oven wouldn’t have become a TV table, and the little girl inspecting, bare hands, the connection and hose of the cylinder would have stirred up panic.

The oven is another type of decor, another type of carpet, reminding them of home. I have no idea what it was for, but they were proud to show it to me. Perhaps one day they’ll have the money to fill up the cylinder, too. I saw improvised cylinder‑exchange centres, but they are probably not for everyday use. Everything seems more expensive when one’s got no income. How to make money with bare hands, this is the essential technique of survival here.

We are in Zaatari, only 13 kilometres away from the Syrian border, in the biggest refugee camp in the Middle East and one of the largest in the world. Five years ago, this was just a tent camp, as temporary refuge for those fleeing the Syrian civil war to Jordan. But the waves of refugees have kept increasing, and in less than a year there had amassed over 150,000 souls. As a city, it would have been the fifth most populous in Jordan. Nearly half a million Syrians have passed through here. In much more troubled times, there were uprisings and even violent clashes with the law enforcement; nobody was allowed to leave the area, surrounded by barbed wire, so it’s no wonder that many felt it like a concentration camp.

In time, the situation has stabilised, the settlement has evolved, it has developed organically, it has discovered, as it went, self‑regulating urbanism. Even through still surrounded by barbed wire (but also by bus stations), it is permanently guarded by armed forces and may not be left without special approvals, Zaatari has become, in time, their city, remodelled, step by step, by the refugees, according to their aspirations and needs.

On realising that they would spend more time here, they started to make the place as familiar and useful as possible, as close to what may have been called home. Families gathered together and even built, in time, micro‑communities, neighbouring, preferably, those of the same cities of origin.

Now the population has stabilized somewhere around 80,000—according to the data provided in the summer of 2017 by the UNHCR (The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) representative: 20% of the camp’s population is under 5 years old, and one of 5 households is headed by a woman; every week, there are, on average, 80 babies born here, and 14,000 medical consultations take place. Over 7,000 children first saw the light of day in Zaatari.

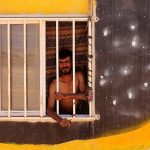

Spreading over an area of approximately 5.3 km2, the over 24,000 modules of pre‑fabricated barracks have become their homes in the truest meaning of the word, through continuous DIY, improvements and improvisations, being embellished, painted, extended by tarpaulins, tents, containers or recycled materials that make up annexes, workshops, patios and even gathering places, nano‑gardens and micro‑oases whose maintenance must be very expensive.

An entrepreneur selling melons improvised a yard at his place, and even built an artesian well in the middle of it, painted in bright colours, surrounded by—mostly plastic— greenery and flowers, and with a silver hawk at the top. It took him some time to power it up, to prove that it was really working, but when a tiny engine started wheezing, and a feeble stream of water started flowing over the stunt that looked to me like a huge wedding cake made by a drunkard, his face lit up with pride.

It was obvious that he would only start up the contraption on special occasions, for which it had gathered around various chairs, sofas, armchairs and pillows: a micro‑community oasis, for chit‑chat or shisha.

But the quintessence of self‑organization, of organic urban development and spirit of initiative under crisis is the camp’s informal marketplace, with its nearly 3,000 stores and small enterprises, mostly operating without license, controls or regulations, creating an urban micro‑economy, and connecting, through vibrant trade exchanges, the Syrians with the population in Northern Jordan.

On the Champs‑Elysees

After the control formalities, which were unavoidably tensioned and long, we entered the camp and we made our way on the main road, which we found out had been nicknamed the Champs‑Élysées by the refugees.

Here, the life of the community spouts, it is an economic pathway and a social network encompassing boutiques, cafes, grills, small shops, ice‑cream parlours, restaurants, and hairdressers’, where the bridal shop will naturally neighbour the repair shop, and the fashion clothes stand, the tatter’s.

On the first day, we gave it a brief look, mostly out of our car, as we had a permanent “tail” on us—and a not very discreet one, either—the police car, so we preferred to wait as much as possible in the barracks where we were invited. And it was alos a lot cooler inside.

They would not cease to express the honour of our having stepped into their home, offering us what they had best. First of all, water. As soon as we would step out of the car and got struck by the desert heat, we would be tempted with water— priceless, especially there: although vital, everyone must buy their drinking water.

If we accepted the invitation, the treatment would continue by coffees, juices and small delicacies. They would do their best to make us forget we were among refugees, that that was not their real home. Their unaffected hospitality and dignity would break one’s heart. Up to the end, we would smile and forget, we would set aside precious questions, exchange small pleasantries instead. It was not until the departure, when the sun would once again strike us down, that we would remember once again the horrors that had brought us there.

This is how my first contact with the Champs‑Élysées also happened. One day, I don’t know what I was thinking, I had left Aman in my undershirt. It was only on the way that our guide and translator, Abo Bakr, noticed and decreed that I could not get in the camp as I was: in their culture, a man would cover his muscles, at least symbolically, otherwise he seemed up to no good, he would be intimidating. I covered myself in a shawl and I got round to the stands on the Champs‑Élysées, in search of a shirt or blouse.

I sweated buckets, as I was only offered “brand” clothing, huge writing on, and when I said I wanted something local, they would show me, grinning: “look, made in Jordan!”. It was impossible for me to get to an understanding with them, but it was also impossible for me to get mad: they wanted all the best for me, as they saw it. They let me ransack all their shelves and when, at last, I stumbled across a simple blouse and put it on, they refused to tell me how much it was, they insisted it was a gift. So I had to leave them some money on the stall and run away, lest they returned it. For me, this became the true Champs‑Élysées. The other one seems to only evoke for me the pretentious parody of humanity.

RefuGIS—for refugees, from refugees

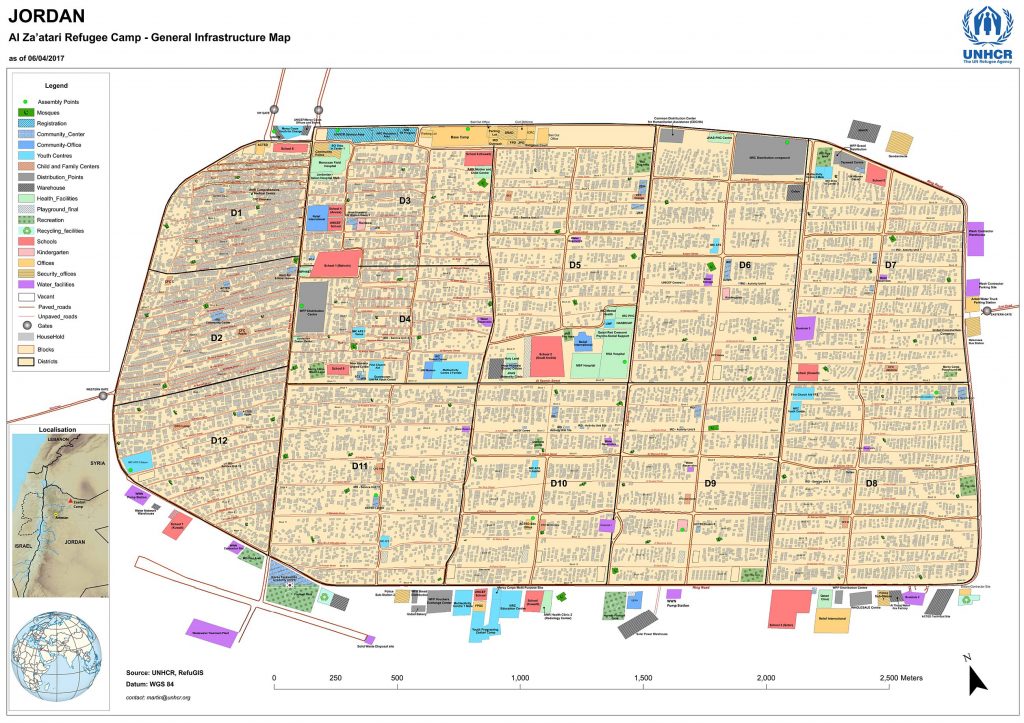

As it soon became crystal clear how easily one could get lost on the seemingly ever‑repeating streets, I was happy when I received, at the meeting with the UNHCR representatives, a map of the camp’s infrastructure, seasoned with some brief information.

In Zaatari there are now 29 schools—where over 20,000 students are learning; 27 community centres for psychological assistance and recreational activities; 2 hospitals; 9 health centres and 1 maternity, playgrounds and sports grounds; countless mosques; offices, warehouses, sewage stations, collection and recycling stations.

An electricity distribution network, powered by a solar plant, will become operational at the end of the year.

Later, I visited a food storage, where photographing was prohibited, so I only recorded the sounds. It’s unsettling to listen to them again: I can see again the trolleys lined up at the cash desks, as in any supermarket, but they are surrounded by a solemn silence, in violent contrast to the hustle and exhilaration by the shelves, where feverish fingers pick out and fill the baskets with foodstuffs and cans of water. An oppressive tension, best rendered by sounds. Later on, I learned that each refugee got, every month, on a card, as humanitarian aid, the equivalent of 20 dollars, to buy whatever they wished in there. Among others, water. Which he would happily share with his better off guests, coming from an european country where the limits of humanity are being endlessly negotiated.

Of the map, I would later learn from its maker, Jean‑Laurent Martin, that he had made it with the support of the refugees, who collected all the data, being co‑opted and trained through the RefuGIS project. As it was, basically, an urban settlement, Zaatari needed the same GIS (Geographical Information System) service as any urban planning office asked to manage infrastructure (for instance, power and water networks) and to provide support to community services.

The inhabitants of Zaatari are especially faced both with basic challenges, such as the food and water shortage, and with a systemic one: the lack of access to means of living and education.

In order to alleviate the two distinct aspects, the UNHCR, together with the Rochester Institute of Technology and International Relief and Development have created RefuGIS, a project that allowed the refugees here to learn and build their necessary GIS services to support their ever‑growing community.

On a global scale, this is the first project where refugees are fully involved in the community decision‑making processes, from emergency planning to the classification of infrastructure. Using their newly‑acquired skills, Refu-GIS participants can create maps to support their discussions on the management of the camp and on community involvement.

War correspondence

I visited the Zaatari camp for a few days, in the beginning of August, through a documentary programme for the fourth edition of the Bucharest Art Week, to have the theme of “War correspondence”, being built around the war in Syria and its consequences.

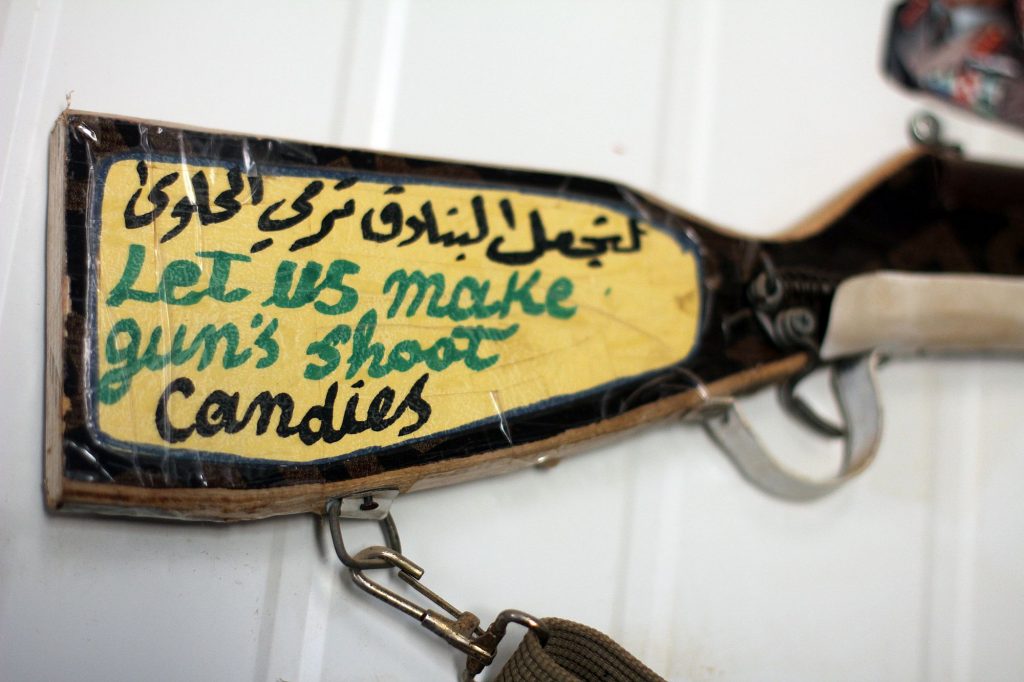

Questions such as the role of the artist and the meaning of contemporary art, otherwise boring, are reformulated in the current context of the war that is shaking the entire Middle East and which affects the entire Europe. It is not easy to find your role in such a theme, sharply brought down from aseptic bubbles or from rarefied strata of socialising networks and media, in the “disarming” confrontation with the eyes of one of the children born in the Syrian refugees’ camp.

The very word “role” suddenly sounds obscene, uncomfortable. When dozens of children chased you through the camp, pulled at your hands, shouting “surra, surra!” and then raising their hands over their eyes to show that all they wanted from you was to take their photograph (but just to take it away as you went, at least their picture should make it out of there), and once you get home you don’t know how to handle these escapes, the words “contemporary” and “art” seem more ridiculous than ever—you feel as hopeless in front of them as in front of war refugees.

The “correspondence” in question is not, in fact, a tale of war, but of the connection that is difficult to create and to stand, between yourself and its immediate consequences—which cross your path, pull at your hands and shout “surra, surra!”

The topic was proposed by Nona Serbanescu, the festival’s initiator and manager, an artist who, we only learned over there, when we happened to catch her crying, was emotionally connected to Syria and to her double origins, Romanian and Syrian.

We were also joined by artists Cristina Iacob, Cristian Munteanu, and Andrei Șerban, and we were accompanied by the Syrian film producer Abo Bakr al Haj Ali, who was our guide, translator and facilitator of meetings. Besides the regular visits to Zaatari, we took about Amman, Mafrak, Irbid and Zarqa, to meet Syrians who resided in Jordan, outside refugee camps.

We tasted, thus, only a few drops of a bitter ocean: 30% of Jordan’s population, nearly 3 million, are residents without citizenship, refugees or illegal immigrants. As of 2010, over 1.4 million Syrian refugees have passed through Jordan, and even if this took a direct toll on it, the country kept on receiving them. In spite of its being among one of the driest countries in the world, and the Jordanians’ means of living were already in jeopardy.

The huge waves of refugees have endangered them even more, draining resources even further, especially water, but also space, food, and work places.

Every time I counted the flags on the panels listing the countries that are involved there in the joint effort of multiplying the palliatives to the humanitarian crisis, I would be ashamed to remember that back home it was still intensely under debate whether the refugee quota that “would be laid at our door”, whether 1000 or 5000 souls, was not too much. Well, when there are 5 million refugees, one would barely cool off a grain of sand. It was in Zaatari alone that a further 7,000 were born.

Yes, let’s get back home. The artists participating in the documentary programme unavoidablyhave returned to contemporary art, exhibiting their experiences at Bucharest Art Week—in the week from 13–21 October 2017. The edition’s special guest was the Syrian artist and curator Humam Alsaliam, who was in charge with the main exhibition of the week. In August, he resided in Bucharest, during the same mobility and documentary programme, organized by the Association for the Promotion of Contemporary Arts, and co‑financed by the Administration of the National Cultural Fund. To be continued. I hope.