We are living in post-Communism in Romania, that is, in a country still defining itself by its relationship to its Communist past. After a long tradition of invented mythologies and counterfeit identities, we are searching for real history. In order for it to exist, we need witnesses and memories to acknowledge, even when shameful. And this is where the museum steps in, with its possible role of mediator, of negotiator in this process of understanding and learning, and, perhaps, ultimately, of healing memories that hurt.

Text: Cosmina Goagea

Photo: Andrei Mărgulescu

The Questions

The collectivization of agriculture in Romania took place between 1949 and 1962, as a mandatory, abusive process, marked by arrests, deportations, loss of human lives. It was designed as part of an objective of installing Communism, namely that of creating an entirely new society, a dictatorship of the proletariat. The failure was complete, and the dramas of peasants being left without all their belongings was overlapped by a long period of poverty and then the post-’89 chaos in agriculture. The disastrous economic effects were doubled by a social rupture, which has not healed yet. Nowadays, questions are many, and not all have been answered:

Where do the people’s distrust, their suspicion, the farmers’ reticence to associate come from?

Why is the public space, instead of being seen as belonging to all, considered as belonging to none?

How have our cities been affected by the estrangement of peasants, moved to blocks of flats overnight?

How much of the relativization of theft is rooted in the Communists’ official lies?

How have ‘local lords’ (regional politicians of huge wealth and power) come to be?

Beyond the political, historical and moral investigation, these questions, asked by Iulian Bulai, the initiator of the Romanian Museum of Collectivization, attempt to discover relationships between the Communist past and its sequels in contemporary society. The museum as a place to better explain the present we are living in – we found this to be a good bet when invited to work on this project. To Iulian’s questions, we have added our own, the Zeppelin staff’s ones: How can one tell a story of a difficult and traumatic past, so that it should truly reach the visitor? And do justice to the topic, inasmuch as possible? In any case, not to do any injustice.

Tămășeni

It was to his family’s home in Tămășeni that Iulian – son of Ioachim son of Bulai – returned, after many years spent abroad, to create the Museum of Collectivization. It all started from his questions, as well as from the heated discussions on claiming property, nationalization, CAP (Agricultural Production Cooperatives), Communists and kulaks, that he had witnessed in his home his entire childhood. In the museum, Ioachim becomes the character telling, from his own and others’ experiences, the story of the family and of the peasants in Tămășeni and in the neighbouring villages, as it actually happened along over 100 years. In 1949, when collectivization started, Ioachim was one year old. But all that has happened since has had a powerful impact on his destiny – his, and that of millions others living through collectivization and Communism. The Collectivization Museum starts from one man’s life, to speak of an entire economic, political, social, and moral phenomenon, whose effects we are facing even today, 70 years later, 30 years since the fall of the Communist regime in Romania.

*Tămășeni Village, Neamț County. To the left, the new house (1941). To the right, the old house (1906). One of the windows preserves the bars installed when this was the police (Miliția) station

*Tămășeni Village, Neamț County. To the left, the new house (1941). To the right, the old house (1906). One of the windows preserves the bars installed when this was the police (Miliția) station

The Destiny

Petru, Ioachim’s great-grandfather, was a hard-working peasant in Tămășeni, a village on the Siret River’s Valley. During the sugar beet boom in Moldavia, in the late 1800s, he leased land which he cultivated. Then he took out a loan and bought a larger plot – arable land, riverside coppice, and grazing land. He died of typhus, in 1918, a young man, leaving his affairs over to his 7 children and his widow. Ianuș, his eldest son, worked even harder, and that is how he bought two mills on the Siret River, and a crossing bridge. He settled them to Petre, Ioachim’s father.

In 1906, great-grandfather Petru builds Ianuș a house. In 1941, grandfather Ianuș builds a house for Petre, with a store and a pub. In the 50s, Communists took almost everything from Petre – except for the grinders, which remain in the courtyard to this day. Besides seizing the land, bridge, and mill, Communists also seized two halves of his houses. One was used to set up the store of the consumers’ cooperative and purchase centre – where Petre works as a state-employed warehouse operative, to be allowed to go on living in his house together with his family. The other became the police (miliție) station. The police station did not function in the old house for too long, but the consumers’ cooperative store remained in the new house until 1992.

*The new house (1941). The shop becomes a Consumer’s Cooperative and Purchase Centre for the Collective

*The new house (1941). The shop becomes a Consumer’s Cooperative and Purchase Centre for the Collective

The Museum

Setting the tone of the story was the most important. We considered that now, 30 years after the fall of Communism, we have the necessary distance for a less heated, calmer, more balanced outlook. In Tămășeni, we found two peasant houses, at a first glance no different from other thousands of houses in other hundreds of villages. But on a closer look, one can see bars on a window in the old house (where the Militia station once was), and the new house has a shop with street access.

The design decision was to leave the houses alone, as the finishes were the original ones, with the decorative wall painting in the Communist era, with woodwork and furniture collected over decades. We were careful to avoid any metaphor, any museification, any excess; to only preserve this brief impression of naturalness, as was the life of people under Communism. Beyond that, the absurdity.

*The Quotas room, in the space once taken up by the shop, then by the Consumer’s Cooperative

*The Quotas room, in the space once taken up by the shop, then by the Consumer’s Cooperative

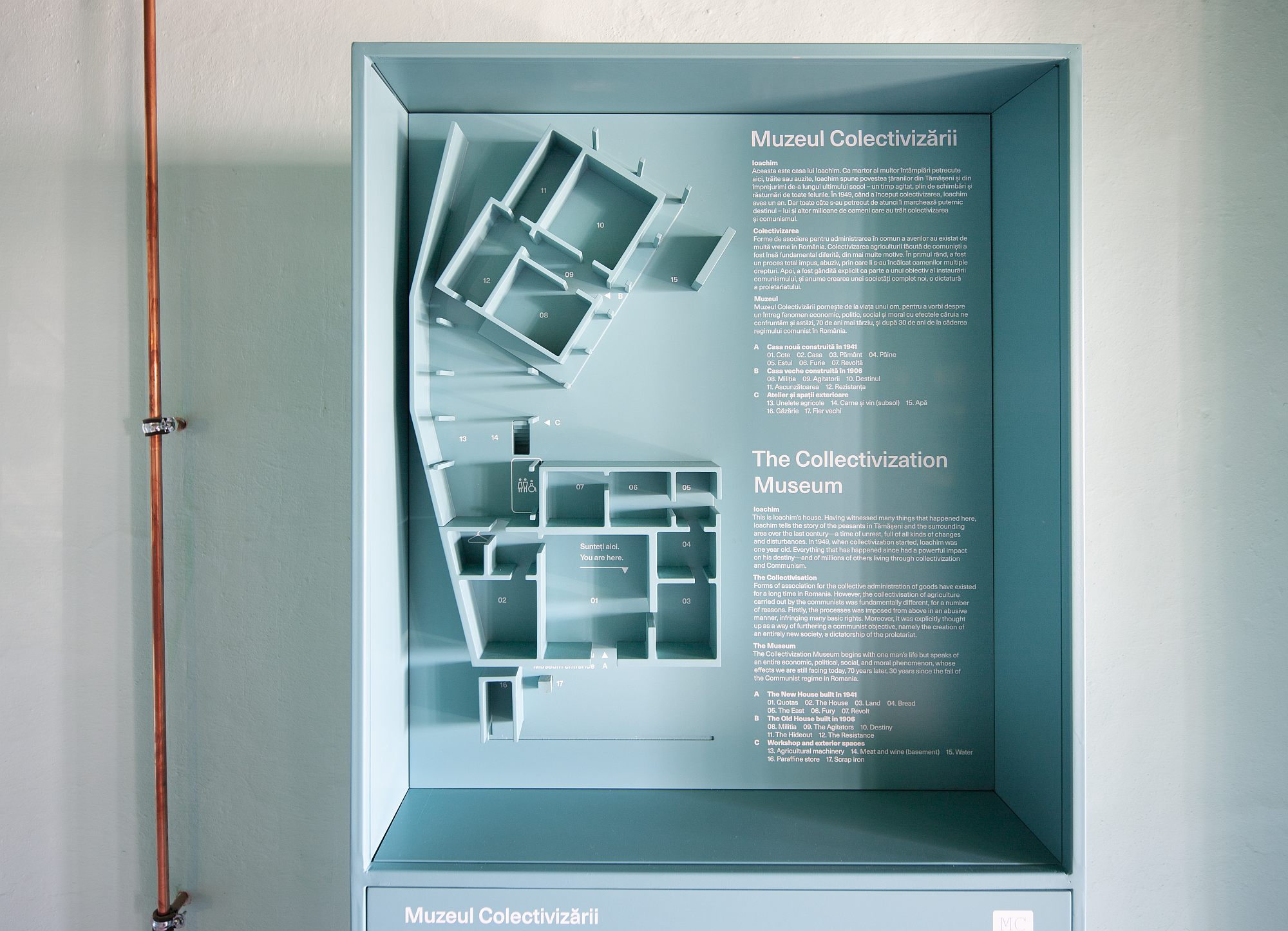

The story of the houses and of this family is in fact a typical one, similar to many others throughout the country. The Purchase Centre for the Collective is used as a pretext to showcase the entire phenomenon of collectivist agriculture. The theme of this museum is structured on 18 distinct spaces (rooms in the two houses, annex spaces, outside spaces), with a specific theme dedicated to each space. These themes are: Quotas, The House, Land, Bread, Fury, Revolt, East, Destiny, Militia, The Agitators, The Hideout, the Resistance, The New Man, Meat and Wine, Water, Gas, Scrap Iron, Agricultural tools. The first 3 rooms were opened in the autumn of 2020 (Quotas, The House, and Land), with the rest of spaces scheduled to open over the next period.

*The tap room shelves and the table where people would drink in the shop were found and placed in their original positions. The missing pieces were replaced by a turquoise metallic fixture, to mark the design intervention

*The tap room shelves and the table where people would drink in the shop were found and placed in their original positions. The missing pieces were replaced by a turquoise metallic fixture, to mark the design intervention

For each theme, the curatorial discourse is organized on 2 different content categories, permanently presented side by side, through two interactive installations in each room.

*Model of the two houses and the thematic structure of the museum over the 18 spaces

*Model of the two houses and the thematic structure of the museum over the 18 spaces

The two categories are:

- The official discourse. This level contains historical, legislative, statistical, etc. information, within the general framework of collectivization, presented in a neutral manner, without over-explanatory texts. The timeline of events and quantifications are the result of archive research, quoting the documentary sources. In the official discourse, there also appear messages sent by the state representatives, the Communist press, the Party’s official reports. The information in this installation is, in turn, split into two registers: the lower side presents the propaganda and agitation channels, with triumphalist photographs presenting happy peasants, staged enthusiasm, placards and tributes – contrasting to the documentary register on top, that of actual life, without embellishments. Perplexity is visible on the faces of people forced to sign away their entire lands to the Collective.

- Ioachim’s story. This level shows the local micro-history, with the Bulai family’s very personal happenings and details, in the various stages of collectivization. The narrative unfolding on this level is based on a series of furniture pieces and original tools, which used to belong to the reality of the houses. The presence of these objects goes beyond set design, as they form a true system of recording memory. This quality is provided by the inventory sheets attached to objects, indicating the track of these pieces within the household, during various moments. The daily objects – some neutral, blended with others, with ideological weight – recompose, on a small scale, a world and a way of living. Similar to Ioachim’s story, these data come from an oral history, learned from the family members, neighbours, other villagers who took part in the events. The installation telling the story also has another unseen register, activated through the spinning of a wheel. A handle dismantled from an agricultural machine or other machinery found on site starts audio fragments of interviews of local peasants, witnesses of the traumatic moments related to the seizure of the land and the forced adhesion to the Collective. Over half a century since the events, the fury, the revolt and the despair can still be traced in their voices, under an apparent resignation.

This approach is meant to present the visitor with an anthropological perspective on what collectivization and Communism meant: that of the individual experiencing life under Communism and transition, alongside their family and close community.

*The „Land” Room. Interactive installation

*The „Land” Room. Interactive installation

The organization on two distinct discourses, an official, and a personal one, represents a re-creation of how the collectivization process actually took place, a process which 3 million people experienced differently. It also speaks of abuse and crimes, of enemies of the people and also of a normality of life in completely abnormal times. Sometimes, these discourses overlap, other times they are completely parallel or even contradict each other. The visitor of the museum is invited to permanently confront the two discourses, to engage in their own quest on different levels of reading and complexity, and to make their own connections between the stories and the events.

*Interactive, mechanical installations: one explains the story of the house, of Ioachim, of the objects in the shop; the other one explains the general political and historical context

*Produse specifice vândute în magazin în perioada comunistă: sticle de ulei, vodcă, rom, precum și cofraje în care se colectau ouăle aduse la centrul de achiziții.

*Produse specifice vândute în magazin în perioada comunistă: sticle de ulei, vodcă, rom, precum și cofraje în care se colectau ouăle aduse la centrul de achiziții.

This is precisely the visiting experience that the museum suggests: not only to provide information, but especially to create relationships. The avoidance of explanations, of over-interpretations, but also of the didactic tone, leaves place for discussions. This museum wishes to engage its visitors in dialogue, to trigger remembrance, to make people talk, acknowledge, understand, ponder, and at the same time to contribute to telling the story of the Communist past. But the discussion is not only about the Communist past, the narrations do not only tell a historical tale, but they influence the very way how this story is told and how we relate to it in the present. There still exists a Communist obsession, radicalizing people’s opinions, making them fail to listen to each other. A discussion of profoundly unjust times can also help affirm the democratic values in today’s Romania. And maybe even recover a culture of being together, because we choose to do so.

*Camera Casa este singurul spațiu din muzeu dedicat vieții private. Construită cu scopul de a fi închiriată, până la urmă această cameră a fost folosită temporar de Ioachim și soția lui, Maria

*Camera Casa este singurul spațiu din muzeu dedicat vieții private. Construită cu scopul de a fi închiriată, până la urmă această cameră a fost folosită temporar de Ioachim și soția lui, Maria

Info & credits

Project initiated by The Romanian Museum of Collectivization Association: Iulian Bulai, Ovidiu Albert, Octavian Parțac, Paul Bălhuc, Eva Marie Bulai

Partner: Asociația Mușatinii Roman/ Mușatinii Roman Association

Curators: Cosmina Goagea, Justin Baroncea, Constantin Goagea, Dragoș Neamu

Historian: Virgiliu Țârău – Universitatea Babeș-Bolyai/Babeș-Bolyai – UBB Cluj

Reasearch contributors: Civic Academy Foundation – Memorial to the Victims of Communism

National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives – CNSAS

The Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes in Romania – IICCMER

Goethe-Institut Bucharest

Museum design and interactive system Development – Zeppelin Design: Cosmina Goagea, Justin Baroncea, Ioana Naniș, Andrei Angelescu, Emanuel Birtea, Cristina Ginara, Alexandru Ivanof, Iulia Panait, Alexandru Voicu, Mugur Grosu, Constantin Goagea

Graphic design and visual identity: Radu Manelici

Translation and proofreading: Anamaria Sasu, Tom Wilson

Craftsmen: Sigmund Pleym Hågensen, Maria Gașpal, Ion Gașpal, Maria Burlacu, Valerian Ilinca, Maria Bulai, Valentin Antonică, Mihai Antonică

Interviews: Anton Giurgi, Ioan Dorcu, Ionel Bulai, Zaharia Aprofirei, Maria Darie, Constantin Darie, Ion Ciupercă, Mihai Pascaru

IImages: AGERPRES, Azopan, Online image Archive of Romanian Communism, Atelierul de grafică, Memorialul Închisoarea Pitești, TV Arheolog

Exhibition production:Q Group Proiect, Acant Design, Azero, Promotas Advertising

Irrigation system and electrical installation: Romuald Bulai – Azzuro, Amalia Căliman, Liviu Căliman, Marian Andrici

Design and construction annex building: MBA 15, Fereastra 1

Supported by:

Hanns Seidel Foundation – HSS

Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom

Konrad Adenauer Stiftung – KAS

Cultural projects supported by the National Cultural Fund Administration – AFCN