Doina Petrescu teaches Architecture and Design Activism at the University of Sheffield and, together with Constantin Petcou, founded Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée, a platform-association intersecting architecture, participative urban planning, activism, acting as a device for addressing societal issues through the participative activation of unused spaces. She has edited the volume Feminist Politics and Poetics of Space (2007) and co-edited works such as The Social (Re)Production of Architecture (2015), alongside Kim Trogal, Architecture and Participation (2005), alongside Jeremy Till and Peter Blundell Jones, Urban Act (2007), a volume edited within the Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée practice, Agency: Working with Uncertain Architectures (2009), together with Florian Kossak, Tatjana Schneider, Renata Tyszczuk and Stephen Walker, or Trans-Local-Act: Cultural Practices Within and Across (2010), together with Constantin Petcou and Nishat Awan. This year, Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée received the New European Bauhaus award, a recognition demonstrating not only the importance of the effort of working ‘together’ for the beneficial development of cities, but also the consolidation of an alternative model of practice in architecture.

Interview: Cătălina Frâncu

Photo: Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée

Cătălina Frâncu: What defines your architecture practice?

Doina Petrescu: I would say that my practice is first of all an activist one: we are attempting, through Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée, to open architectural practice to all those who wish to use it as an instrument of critical thinking and intervention within the society. Architecture, whether ephemeral or not, has the power of bringing major and long-standing changes in the world. As architecture is lived and experienced directly, people can appropriate it, can understand the difference between a space designed to help them grow or to restrain them. Together with my partner, Constantin Petcou, with whom I co-founded the AAA, we imagined the studio as a generator of participative practice, and we designed it as a civic organization. Although we knew this would limit our capacity to build, we decided to also keep our practice open to non-architects. In France, you can build up to 200 sqm without signature right.

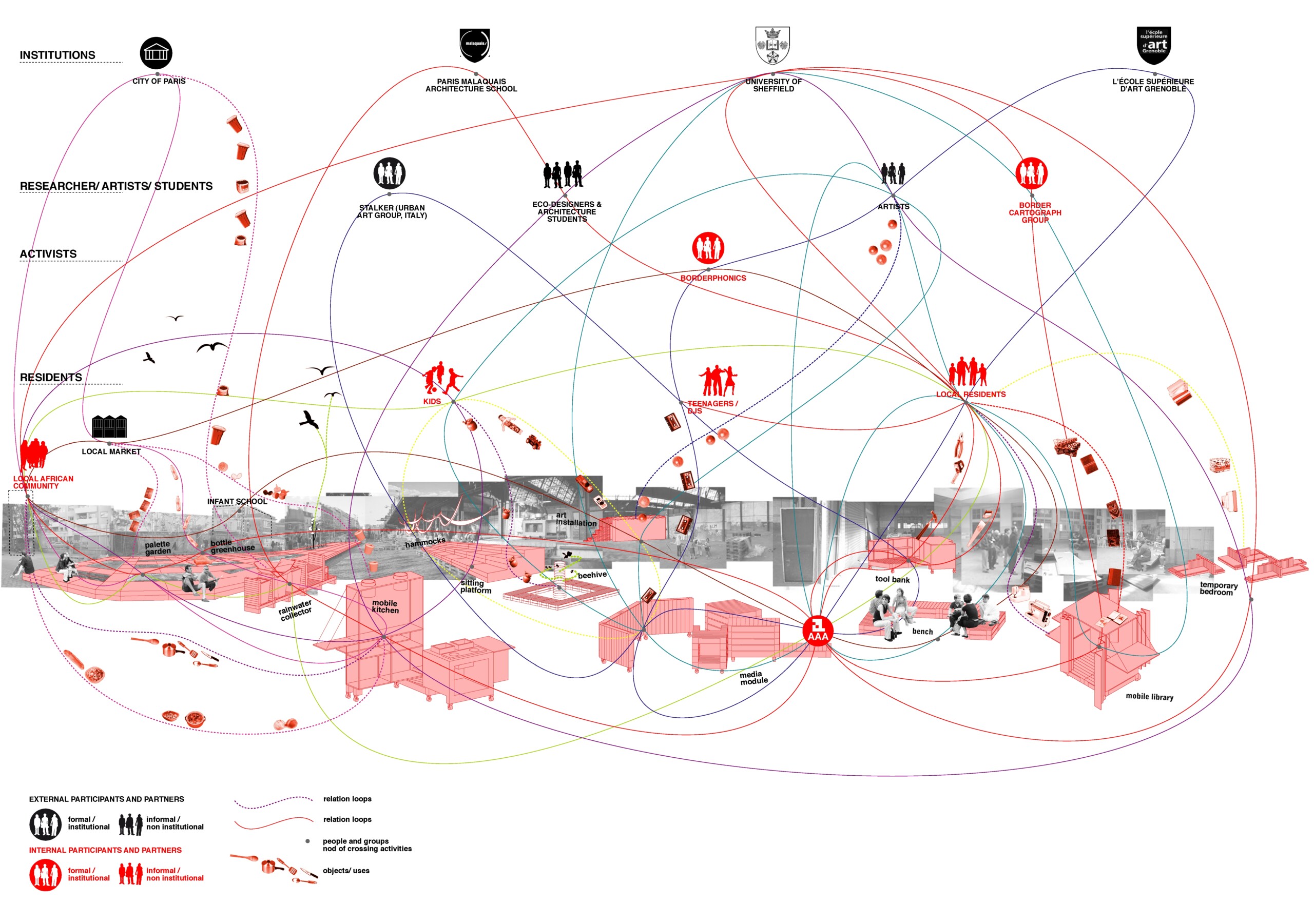

We understand architecture not just as an object, but also as a process: to us, the building is a means, a tool, not an end. The purpose is firstly to create communities within the contexts where we act, and ultimately to change the society where we live. It seems utopic, right? Architecture has several dimensions: space is an economic, social, and political product. Our stance in architecture can also be read through the graphical representations that we are working with. We are especially interested in social architecture, which we are representing via diagrams, where architecture is present as an actor in a network of other actors: customers, financiers, political representatives, etc., and all the material and immaterial relationships between them. This is very much in the sense of Bruno Latour’s Actor-network Theory.

We have chosen to show, through the very name of the association, how we relate to architecture and the society: ‘self-managed architecture’ (architecture autogérée) is self-explanatory in that the result of the architecture process will be used, managed, and altered by its users, who continue to improve on the result. The name has become our banner’s ‘coat of arms’: it has brought us recognition (we are very easy to identify, and our positioning is quickly understood), but it has also had a negative impact: when applying for grants from (‘right-wing’) municipalities, we were accused of anarchism, as self-management is an important concept in anarchism theory. We lost some funding opportunities because of it. We never seek to work in certain contexts (i.e., ‘left-wing’ or ‘right-wing’), but where it is needed: in general, in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, in the suburbs. These areas are essential for the metropolitan area. Many of them are urban failures, built upon the principles of Modernist urbanism, for the ‘ideal man’, but were forced to host a population with high cultural heterogeneity, one which is socially and economically marginalised. We were very interested to see how we could build self-management capacity within the population here. We wanted to contribute to giving back to the inhabitants the power of shaping their own future of dwelling, at odds with what had happened in the past, which was built without consulting them. We have always sought to make projects in collective formulas. Individualism is encouraged in the contemporary, post-capitalist society, and people have forgotten how to work together. Our projects are also a pretext to rebuild this feeling of community, we are talking a lot about sharing cities, about the collective city where things are done in common. The idea of ‘working together’ has been very important to us, ever since AAA was set up, in 2001.

*“Agrocité“ – micro-farm for urban agriculture and ecological education, Colombes, 2013-2014

*“Agrocité“ – micro-farm for urban agriculture and ecological education, Colombes, 2013-2014

C.F.: In the book you edited, Altering Practices, I read: “We can also talk about Altering Practices as practices of ‘curating’, of ‘care taking’, acknowledging the work of reconstruction and re-production that bears ethical and emotional charge, the kind of work that was always associated with women.” I think the title of the book is very eloquent: alter as other, alternative and alteration of what already exists, also holistically refers to the positions of ‘minor’ narratives so far. How much of this concentration do you think is generated by your being a woman and do you think these lenses have allowed you to experience different realities, as compared to your men counterparts in architecture?

D.P.: I happened to approach feminism through my studies in Paris, in an inter-disciplinary department of ‘feminist studies’, which was very useful to me in architecture to generate a position which is both critical and open to other disciplines. I have managed to build a discourse that goes beyond the political and I have brought it to my own practice. Altering Practices is clearly a feminist book, resulted from a conference I organised in Paris in 1999, and the initiative and interest in this topic also derives from my being a woman: the way I position myself in relation to the world is informed by this capacity.

C.F.: Many women in architecture avoid speaking of their gender, perhaps out of the desire to avoid being labelled as successful architects ‘despite their femininity’, a discourse that places femininity in the ‘disability’ category. Of course, there is also a desire to avoid observations such as “you’re a good architect, for a woman”. Another reason to avoid the gender discourse is to circumvent having one’s success attributed to ‘positive discrimination’. Such a desire is self-explanatory, as those are restrictive visions of a distorted reality. Nevertheless, this silencing is not supportive of the dialogue on inclusion of the multiple voices in the urban environment. How can we counteract the narrative that women need to give up femininity to be good architects? The same question stands for disabled persons, various ethnicities etc.

D.P.: In England and France, it is increasingly easy for qualities of difference in the architecture profession to be acknowledged; I even notice it with my students – they are very open to the articulation of a feminist position. I strongly believe that asserting, through your practice, that you are of a different gender, race, class, and culture than the dominant group can only bring richness to your field. Of course, one can easily reach conflict as well, because it is not easy for patriarchal societies to accept values they have so far excluded. It is a matter of loss of power. But the conflict is a very good catalyst of democracy, as long as it is solved in a constructive manner. I know that in Romania, the same as elsewhere, being a woman in architecture is not necessarily a comfortable position, but I continue to believe that diversity is a force and a wealth in any field. Diversity is a general ecologic principle, if you will, and one must fight to preserve it!

C.F.: Do you agree that, in parallel with the grand narratives of urban practices, there have always been other intentions and intentionalities which have shaped the cities where we live? We rarely see them out of their context, as it happens in the case of urban masterplans, and they are most often integrated in ‘common’ models, which are rarely highlighted. Besides, they are often analysed by the marginalised: people who rarely fit within the grand narratives, from women to immigrants, disabled persons etc. Together with the AAA team, you have started to study their growth and positive impact. What drove this initiative?

D.P.: The decision to include inhabitants, users, and citizens in general in our practice arose paradoxically from the Romanian experience, where interest in participative architecture was born in the Communist period out of the (unconstrained) experience of working with others. One of our first projects in Romania entailed building a gallery for and together with plastic artists in Râmnicu Vâlcea. Another example is the showroom we built together with some workers from the factory where Constantin was working as a designer, so everything would always be created through collaboration. With the fall of Communism, when we moved to France, we were both disappointed in the top-down and individualist approach of the capitalist society we found there. We had been used to a top-down approach by the totalitarian Romanian state, but it came as a surprise to also see it in France. It was then that we started to volunteer, in our spare time, creating participative projects. The experience of working ‘together’ has stayed with us, and financing also started to increase and diversify – from cultural, to local and to European funds. Then came recognition: several international awards (some 12-13 over the last decade), culminating in the New European Bauhaus award this year. It’s a very important step, which underlines that this type of architecture practice is very necessary in Europe.

C.F.: Could we say that a ‘marginalized experience’ is a fertile land to shape a healthier city for us all? How would this manifest in urban practice?

D.P.: I wouldn’t necessarily speak of marginalization. ‘Marginal’ – how? Who says what is marginal? We realised, for instance, while doing research on intervention impact and user public, that people frequenting the projects we develop have a much lower carbon footprint than middle class people in Paris, for instance. I think we have a lot to learn from people who are used to living with less: the experience of marginalization generates less waste, is less consumption-based, they mostly use public transport and often bring, thanks to their background, a culture of redistributing resources, goods, and time, which are essential elements for a sustainable development.

C.F.: The kitchen is part of a universe that has been historically understood as an exclusively feminine one. Zaha Hadid, the first woman starchitect, decided not to build one in her own house, a gesture that was read by many as a denial of femininity in architectural practice. You have developed a device called “Cuisine Urbaine”, within the Ecobox project, focused on the act of cooking together and of building a community, an antithetical gesture which, instead of erasing the feminine out of architecture, eliminates it from an important apparatus, the kitchen, and gives it back to all, while at the same time stressing the social importance of ‘care taking’ as a gender-less value. How was it received?

D.P.: Ecobox is a system-project, consisting of a series of devices meant to support inhabitants in their various collective neighbourhood practices. Among the system’s elements there is a workbench for DIY, a media lab, a mobile garden, and the kitchen you have mentioned; they were all developed together with the community. Indeed, ‘food’ involves all and serves all, without regard to gender roles or other social positions. Everyone has equal access and is invited to cook together. Food is a social binder; people gather around food. This is indeed about ‘care’, about how to take care of and to support the community in everyday life. We also build shared moments of connection at the University, when eating. Everyone brings something they have cooked themselves and we have serious discussions, like in the ancient feasts.

Zaha Hadid’s architecture is indeed very different and without correspondence in our approach. First, she has worked with a lot of resources in and for social classes where the act of making together is incomprehensible.

*EcoBox project. Diagram of relations

*EcoBox project. Diagram of relations

C.F.: What are the strong points and the dangers of the AAA’s architecture and urbanism practice?

D.P.: That’s an interesting question. One of its strong points is that participative architecture has a large social impact, it is inclusive, it involves many actors in development, and it creates connections. We are very careful of this aspect, and we are actively working to change, through our practice, public policies and attitudes towards the set-up of the urban space which we wish to be more democratic, more ecological, more just.

One of the challenges appears when we take a step back from management: often, there are negotiations on who will be managing the project we built together. It sometimes happens that this responsibility is taken over by the municipality, other times, some of the members of the community take charge. A second challenge is related to the time we need to invest in each project. In order to be able to complete them, we need time and funding from alternative sources. Having different projects with different types of funding makes AAA’s practice’s resilience possible.

*Eco-interstice “Passage 56“, 2007. Project team: Constantin Petcou, Doina Petrescu, Raimund Binder, Sandra Pauquet, Nolwenn Marchand

*Eco-interstice “Passage 56“, 2007. Project team: Constantin Petcou, Doina Petrescu, Raimund Binder, Sandra Pauquet, Nolwenn Marchand

C.F.: In lieu of a conclusion, what is an inclusive city to you?

D.P.: As Constantin mentioned in our previous interview for Zeppelin (issue 156/winter 2019-2020), while we were working on the Ecobox project, which took up several spaces in the neighbourhood, both indoors, and outdoors, one of the African children we were working with exclaimed, seeing a bunch of keys Constantin was using: ‘Wow, do you have the keys to the whole city?!’ and Constantin replied: ‘Yes. And if you keep on working with everyone here, so will you.’

The inclusive city is a city of spaces open to everyone, a city where communities can be created, starting from the immediate vicinity up to the workplace and beyond. We may never hold the keys to everywhere, but we will hold those that open the gates to conviviality. We, architects, hold a few keys and can also open doors for the others.