The neighborhood is beautiful but a bit strange. It’s part of the extended historical center, yet very peaceful: the usual rows of Prague houses are mingling with large parks, clinics and former abbies such as Emaus. In the former garden of the monastery four prisms above a plinth house the Prague Institute of Planning and Development, and, on much of the ground floor, the CAMP, one of the most alive architecture institutions in Europe.

Text: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Foto: BoysPlayNice, Benedikt Markel, Maly

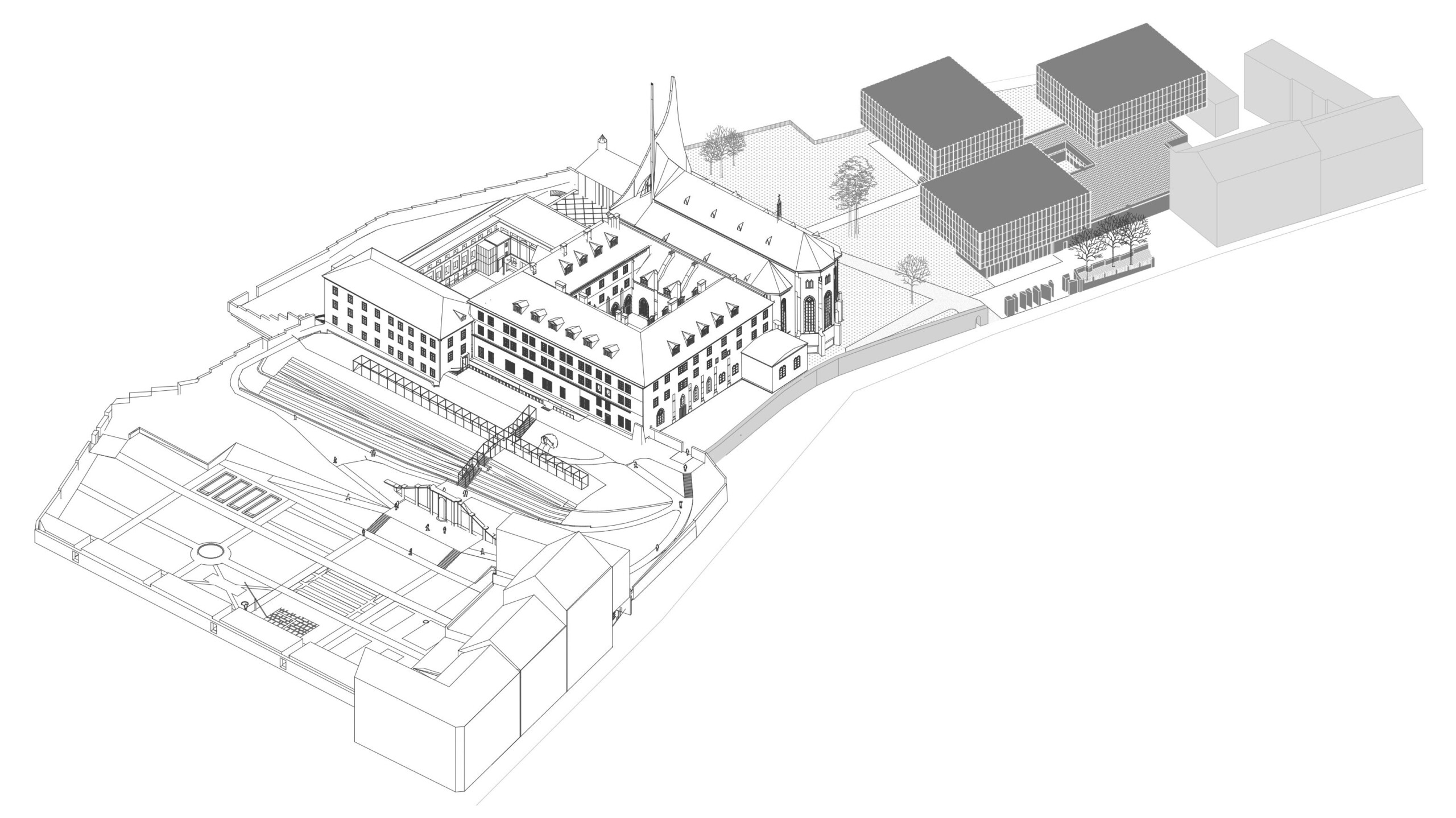

I went there to talk about involving the public in urban development, public service and cultural energies and also about a new life for post-war heritage with Štěpán Bärtl, director, Benedikt Markel from NOT BAD , the architects of the refurbishment and Sandra Karácsony from the Czech Centrs Headquarters in Prague.  *Axonometry of the site. In the center, Emaus monastery, right, its former garden and the IRP center

*Axonometry of the site. In the center, Emaus monastery, right, its former garden and the IRP center

The building, a work of Karl Prager, one of the masters of Czech architecture from the 60s and 70s, is not just beautiful (at least for architects), but also open and friendly, a far cry from the impresive, but often grim and forbidding buildings from that period. We discussed in the hall/café/library and afterwards, I looked at two of the exhibition and then worked and lunched for a couple of hours. It felt great; people around me ranged from the unmistakable architects and architecture students to kids, teenagers, a lot of eldelry people, couples hanging out. (Ș.G.)

*Entrance and view from the garden © BoysPlayNice

*Entrance and view from the garden © BoysPlayNice

Ștefan Ghenciulescu: Let’s talk about the building and the institution. What was the purpose of the original project and what type of institution is CAMP?

Štěpán Bärtl: The building was a late 1960s design, but only realized in the 70s: a center for the socialist planning institutes – architecture, planning, infrastructure, everything… An expression of the re-centralization and increasing control after 1968. The area, part of the former grounds of the Emaus monastery, remained a city property through all these years, and was always connected, in various shapes, to planning.

Currently it houses the Prague Institute of Planning and Development, which came into being in 2013. Camp is part of IPR, but also functions as an autonomous entity, an organization within an organization.

Around 2013 in Prague, urban and land use planning had a very bad name, very bad connotations in terms of corruption, wild development etc. Consequently, a lot of bottom-up initiatives fighting against that, and carrying projects for new public spaces, sprung up. IPR was envisioned by mayor Tomáš Hudeček as a kind of think-tank, funded by the city, but functioning independently, able to talk to the public, and throw ideas at politicians while not being dependent on electoral cycles. So, IPR is a top-down project, but it started with a lot of people from NGOs and bottom-up initiatives, as well as practising architects that decided it was time to give something back and work for the city.

“White Hall”, ground floor © Maly

“White Hall”, ground floor © Maly

The main goal of CAMP is to inform the public about urban development. Instead of investing into PR campaigns, externalizing to marketing agencies, everything is done in-house. CAMP and IPR are extremely connected. A very large part of our content comes from the IPR, which, to give you the scale, is composed of about 200 people – architects, urban planners, geographers, sociologists, data analysts. They are our brain trust, and we are the form-givers.

We house exhibitions, but we are not a museum. There are other places in the city that deal with architecture – the Jaroslav Fragner or the ViPer Galleries, for instance. Our role is not to compete with them, but that of an information center. Anyone who comes and asks what’s going to happen to their street, to their park, to their neighborhood, should find the answer here. While being emphatically Prague-centric, we are, of course, in contact with all the other institutes and other city architects, and the topics are very interconnected.

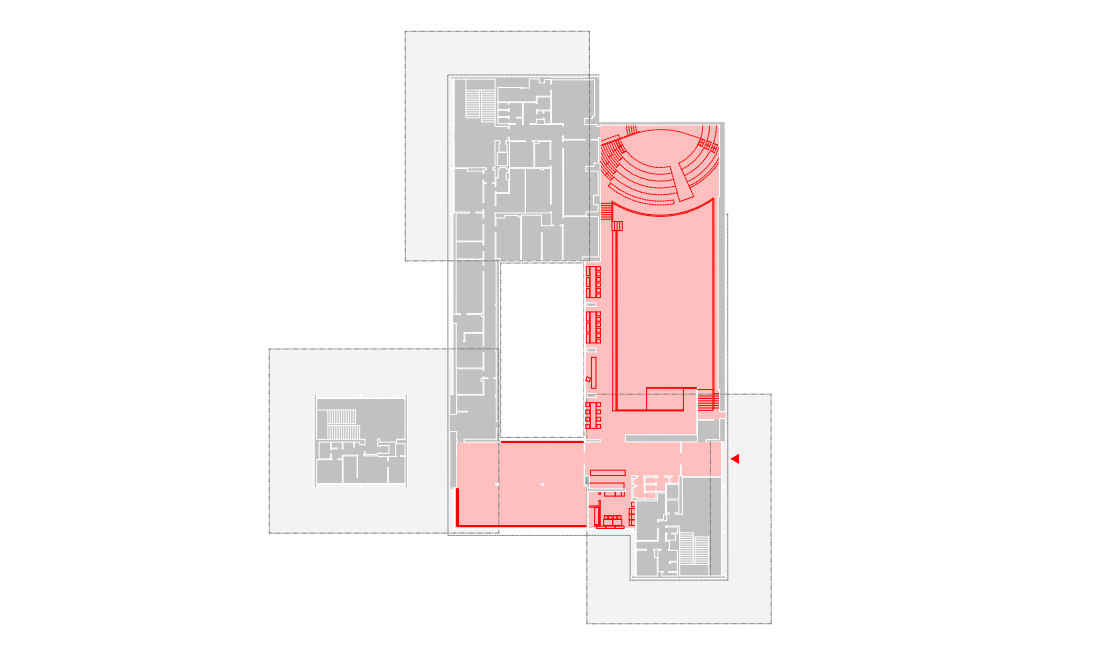

*Plan. In the center, the “White Hall”, right, the entrance, the book shop and cafeteria, the “Black Hall”

*Plan. In the center, the “White Hall”, right, the entrance, the book shop and cafeteria, the “Black Hall”

Ș. G.: You talked about people wanting to know about their street and their city. Is the percentage of non-architects in your audience really high?

Š. B.: They are definitely in the majority. And that’s one big difference from the other architectural centers. The other lies in our focus on the present and the future; after all, there are so many institutions that the institutions that deal with the history of Prague.

We see ourselves as translators between the professionals and the general public. Actually, a lot of the CAMP staff, including myself, don’t have a formal architectural background. The center itself was partly founded by non-architects, as well. The citizens of the cities are the people that we need to be spending time with and to attract.

Ș. G.: How do you grab them, actually? Targeting the children and the younger generation, or by emphasizing the hot topics?

Š. B.: Both. Also, multidisciplinary teams are naturally closer to the general public. It’s crucial to say things as they are, but without sounding too complicated, too hermetic. You know, people enjoy the city, they may feel good or bad in a place, without necessary knowing how to put a label on them.

Our audience is composed of civic-minded people; and we are trying to reach outside the young and well-educated groups. For instance, we were present in a Sunday TV show, that a lot of elderly people watch. But we are also working with the authors of an important comic-book series for children, on a story on how kids can go into the city, experience and influence it. But, as you see, people even come here for just a coffee, to work. Sometimes they peak into the exhibition and this sparks an interest. That’s one of our main tasks – to spark an interest.

The different formats also work within the same project. An exhibition centered on projections, for instance, tends to discriminate a part of the audience. That’s why we also provide the content in analog form, in a small and attractive catalogue that’s always available for free. You can choose the way you want to consume the information.

One of our exhibition dealt with the planning strategy for Prague. In its actual form, the strategy is a book with 1000 pages, that almost nobody ever entirely reads. So we turned it into a game, in a kind of SimCity format, where you could be mayor for an hour. We called it Imagine Prague, and it became a great success, including with kids.

*Entrance hall, books shop. One can already notice the “grid of points” © Benedikt Markel

*Entrance hall, books shop. One can already notice the “grid of points” © Benedikt Markel

Ș. G.: Are your producing the editing and the design in-house?

Š. B.: The content, yes; for most of our printed material, we have been working since the beginning with the Ex Lovers graphic design studio. They were part of the team that designed our visual identity. The continuity helps in keeping the overall consistency of our output and our identity.

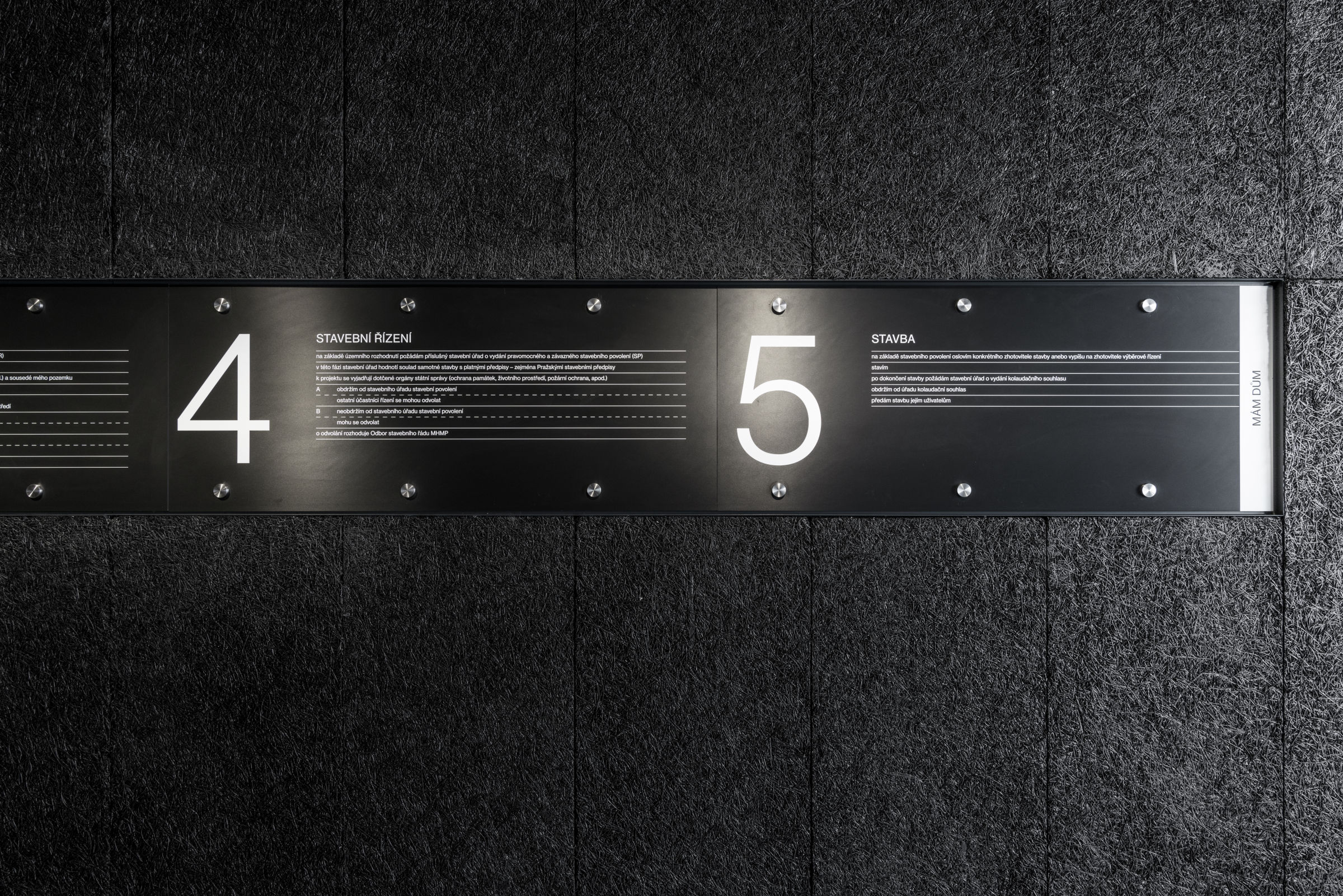

*Grid of points and various instances of the visual identity © Benedikt Markel

*Grid of points and various instances of the visual identity © Benedikt Markel

Ș.G.: I would like us to discuss two very sensitive topics. The first one, of course, is money. Drastic unding cuts for culture are now happening all over Europe and at all levels. Institutions that were rock-solid have now to shrink and adapt. How do you deal with this – in relation to the administration, regarding partial self-sustainability etc.?

Š. B.: Our core mandate is to for an information center. And, yes, we developed this into an urban cultural hub too, but, essentially we get funding in order to provide a service for the citizens. Of course, there are pressures to cut funding for all activities in the city administration. One part of the strategy is the quality of what we are doing – to be and to show that we are useful. Then again, Camp costs money, but it’s extremely cheap compared to other city projects. We always say that we cost the same as one centimeter of the underground tunnel under construction.

Very importantly, we also provide a platform for the administrators of the city to speak about public projects. They get a friendly place for this, an audience, and a direct feedback. And that’s precious. As to self-financing, we do rent-out spaces and we can also access sponsors, but within a very strict frame: we will not take money from a developer, to show their project in an exhibition. If the project is important for the city, we will organize an exhibition on it, but without taking money from the investor.

The Anglo-Saxon model of strong private funding – and then strong dependence from the financers – doesn’t suit us.

*The “Black Hall”, semi-basement and basement © BoysPlayNice

*The “Black Hall”, semi-basement and basement © BoysPlayNice

Ș.G.: That brings me to my second tough question: you are a public institution but you might find yourself in the situation to criticize public projects.. There are so many pressures and interests… My question is actually about independence, continuity, diplomacy.

Š. B.: Firstly, I can emphatically say, I’ve never felt that we were at any point pressured into doing or not doing something. As to diplomacy, criticizing and so on, sometimes it’s more effective and more in line with our mission to do this through our curatorial program, through the choice of topics and guests. Last year, we invited Janette Sadik-Khan (the former commissioner for the New York Department of Transportation, now an international consultant). Instead of shouting that we should take out most cars from the city center of Prague, she said it for us. A lot of people didn’t agree with this, and the result was a very balanced discussion.

The funny thing is that we are criticized from different sides. A lot of developers claim we are part of the left, liberal anti-car, cycling lobby etc., while for a of the public, we are lobbying for the investors. If everybody is angry or satisfied at the same level, maybe that means we’re walking the line in the middle and that’s what we’re supposed to be doing.

*The “Black Hall”, Metropolitan Plan exhibition © Maly

*The “Black Hall”, Metropolitan Plan exhibition © Maly

Ș.G.: Let’s get to the building and the refurbishment. What can you tell me about the brief, the ideas and the process?

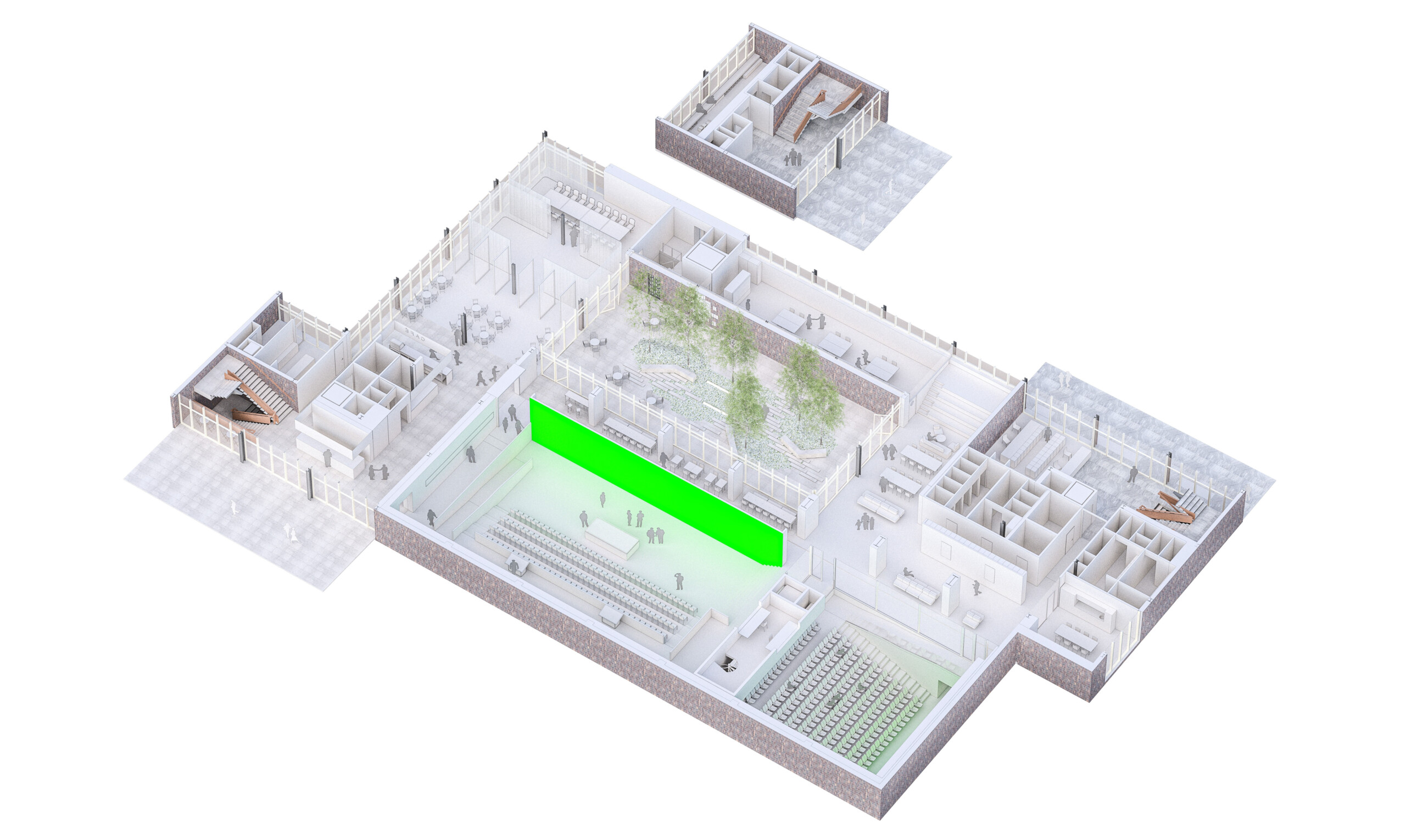

Benedikt Markel: Looking back to 2016, the starting point of designing CAMP was quite complicated. This was not an empty space; rather, construction of a completely different concept for an exhibition hall was underway. For instance, the exhibition hall housed a permanent display for city and zone planning with very fragmented and complex spaces. The institutional change brought another philosophy: an open-space ground floor, able to house several programs and types of exhibition. Additionally, the original Karl Prager design was covered to a large extent by plasterboard walls etc. The operation (actually done on a tight budget) only covered the ground floor spaces for CAMP.

*General rehabilitation plan for the IRP: Ground floor

*General rehabilitation plan for the IRP: Ground floor

Š. B.: This part may look fresh, but the rest of the building very much remains in a poor state. We are in the process of convincing the city that it’s a worthwhile to invest in this building, which should be heritage protected and hopefully will be heritage protected soon. This status is vital, because the state of the building worsens with every year, and therefore the refurbishment will become increasingly difficult. This is prime real estate, after all, and lots of people don’t appreciate this architecture and would love to take it down and build something else here. We are at a crossroad and the general environment of austerity doesn’t make things easier. The refurbishment for CAMP was about 10 % of the budget for the whole building. It’s a first step.

We envision this as a model project for saving, healing and repurposing this type of building. Especially since a lot of architecture from that period has been torn down. Here we also have to deal with the bad renovation from the early 90s.

Refurbishment actually concerns the whole plot. The park and the buildings have to open-up; this is a public space, but one that has been too long outside the mind map of most people in Prague.

B.M.: We developed a design for the general refurbishment of the IRP building in 2021. But it’s a huge challenge. The refurbishment for the entire IPR building will cost more than building a similar volume from scratch, while most of the money will go into installations, etc., therefore in things you won’t be able to see. Moreover, due to the building’s division into three volumes and its large overhanging cantilevers, it is also very challenging to renovate it to meet today’s thermal-technical standards.

As to the design of the ground floor, we aimed to honor Karl Prager’s architecture, by “cleaning-up” the bad additions, and being as respectful as possible. The interventions try to answer the present needs but also to develop Prager’s logic.

One of the main elements in this respect is the “grid of dots”. The building is obsessively modular, based on main and secondary grids. In the stairways you find large boards mounted from evenly spaced large round elements made of brass. We multiplied them. But our dots are made of steel and through contemporary technology. They mainly serve for exhibitions and visuals of any kind, for supporting the shelves in the bookshop etc. They are repeated as a serigraphy on the glazed walls. The grids and dots at their intersections became an essential part of the new visual identity, visible in both the graphics and the physical space. You can find them on the website, in every printed output, piece of furniture etc.

Prager was really obsessed with grids, prefabrication. Because of the rigid standardization in the Socialist building industry, he had to invent his own system, which he used in all of his design from that period. You can see it here – the aluminum profiles, fan coils and heating systems, the soffits … everything very sophisticated.

Ș.G.: Some finishing statement for the interview?

Š. B.: Well, maybe something about the practical functioning of the center. We are open six days a week, 12 hours per day, more like a public space than a museum. The expanded opening hours are also meant to accomodate a very complex schedule – we have about 20 to 30 events every month. Escpecially in the morning, the program is rather Tetris-like, as you have to find a place for everything. On a typical day, you would find a program for children in the morning, or perhaps a professional conference, then guided tours in the afternoon, a film or another event for the general public in the evening. So you can check that out on the website, the different types of programs.

Maybe that’s one of the things that sets us apart from other centers: we are extremely event-based. And the design supports that – the spaces are flexible and connected, yet with their own identity; you can go straight from a black-box to a very open space.

We strived hard not to create a hipster center, which obviously is the easiest target audience. We spend a lot of time on remaining accessible. Of course, accessibility also means that we organize a lot of haptic tours for the visual impaired audience, that all our events are translated into sign language etc.

Maybe this is what can be taken as an example for other public cultural institutions.

B.M.: I would like to add that, despite all technical and economic problems, it’s architecturally easy to refurbish a building like this, because there’s no evil in it. Just not one single bad idea. This is thanks to the architect, but also to the fact that, despite the political regime, there were almost no pressures – there was a huge freedom for design, and Prager was able to come very close to his dream of a modern building, “like in the West”. And the rigorous modularity makes it very easy to change installations, to insert new technologies, add elements… its principles are unbreakable.

Š. B.: “The Prager Cubes”, as the complex is called, is not one of his most famous works. But we love it and we are very proud to work in it.

Info & credits

Concept authors: Adam Gebrian, Eugen Liška, Adam Švejda

Architectural studio: NOT BAD: Benedikt Markel, Dominik Saitl

Collaborators: Martina Požárová, Vilém Kocáb

Location:Vyšehradská 51, Praga/Prague

Completion year: 2019

Gross floor area:1100 m2

Investor: Orașul Praga/City of Prague

Implementer: Prague Institute of Planning and Development

Visual identity: Ex Lovers & Martin Groch

Construction: CONTRACTIS

AV presentation: st.dio (Josef Kortan, Jakub Roček)

Lighting: Ateliér světlené techniky (Ladislav Tikovský)

Electrics: Apollo Art (Jaroslav Zuna)