Handbook for the creative industry man: Low-profile and efficient Amsterdam

No more, no less than an entire weekend, I wandered through the hippest places in Amsterdam looking for older or newer industrial areas that have been temporarily converted to accommodate creative projects. My aim was to discover what makes them work ‘over there’ and not yet here, and how come no one takes full advantage of the large scale industrial areas in Bucharest. Amsterdam is abounds of industrial areas of all sorts, from the more red brick shed roofed picturesque ones to those dating from the 70-90’s, built with concrete prefabricated, industrialized components, much resembling the ones from our socialist era. Considering the fact that the industry is relocating on a global scale or is becoming completely automatised, land within the city is priceless and industrial areas have become the latest trend, I thought it obvious that I would find here something interesting to learn from.

What makes these places in Amsterdam “tick” nowadays is not by any means a miraculous investment plan, neither an ambitious project, but, on the contrary refraining from any new construction. A definite and definitive NO to any change to the places and things that were found on site, moreover, efforts are directed towards recycling any existing on-site resources. Architectural projects are usually non-existent, interior designed is limited to emphasizing what is already there, and restoration is brought to the state of science here, but is also a matter of common sense and building tradition engrained in public conscience. Consequently, large high risk, unpredictable investments are replaced by an event, marketing and communication plan. Spaces manage to become alive, accessible to the public of all backgrounds and produce some income by means of cooperation between several groups and organisations.

NDSM

may be compared to an industrial island North from Amsterdam Central Station. For a five minute ferry ride you find yourself in what was once an active dock. Given the fact that industrial activity was moved or underwent decline, and storage spaces and boats have been abandoned, squatters soon settled in at the beginning of the 60s. This process went on until the beginning of the 2000s when a group of, let’s call them, activators proposed a very simple action plan. Artists, actors and film directors, skaters and of course architects set their minds to create a place for communities that came together spontaneously, but also for something more. Taking advantage of the outstanding resources : hangars, warehouses, navigable canal, containers and cranes, they got to thinking about a large scale enterprise. Not so much referring to the construction as to the way the space is used.

For example the main hall (which is actually enormous with a surface larger than 10 football stadiums, with a height of 20 m, a beautiful red brick metallic beams construction) has become the central action area for the entire area. The only elements installed in it have been simple metal frames, practically only beams and pillars and some platforms and access stairs. Creative industry people have been invited to ‘set up shop’, from small production, print shops, architecture, interior design to pubs, bars and venues for events. Offices, housing, music studios, small restaurants, kitchens, performance areas and above all a skate park popped up on the premises, built for very little cost from panels, boards, recycled material found on site and benefitting with access to all facilities. Approximately 200 companies occupy these spaces at this current time and everyone has ‘manufactured’, within the metallic frames, by their own capacity and talent, their walls, showcase and sometimes even their garden. Over the course of time, this organised form of ‘favela’ has started looking like a mini city with streets, a map and postal addresses, with public squares that form fertile grounds for creative or artistic entrepreneurship but also offer to the wider public high quality underground cultural production and of course alternative entertainment.

Following the experience within the small hangar city, out on the freight docks again, I discovered two restaurants: one built from containers and the other from polycarbonate, both still retaining in some way the local picturesque. Pllek and Northern Light also have a contribution to the charm of the area, offering space for events and special gastronomic culture.

Since we’re already on the topic of restaurants, I would also mention de Goudfazant, Stork Hotels (also in the northern area) and Trouw and Baut on the eastern part of the city. The first two hosted also in old industrial sites, and the latter in former headquarters of newspaper printing industries.

Here either, the idea of a large scale architectural or functional conversion project of these areas does not exist. The extent of the interventions is limited solely to ‘endearing’ design gestures, installations or small objects placed in surprising locations. The furniture is recycled from other factories, and is, in any case treated as a minor element. Humor is the perfect recipe for these situations: a pick-up in the bathroom is only one example, but examples and tiny surprises are to be found every step of the way. The major investment focuses on the kitchen and service, that have needs to rise up to the challenge in terms of speed, and setting difference, but also on a permanent program for events, a model that states that the audience is the one that needs to be cultivated and engaged.

The conclusion of these tandem articles states that the recipe might be applied to our context..if only it could benefit from a cultural model that would allow it to spring. The three Rs that we may operate with in the current situation are: Recycling, Reversibility of solution and a little bit of Refrain from ambitious large scale plans. Less is more, as they used to say.

Filaret Power Station

Text: Irina Diamandescu

Foto: Camil Diamandescu

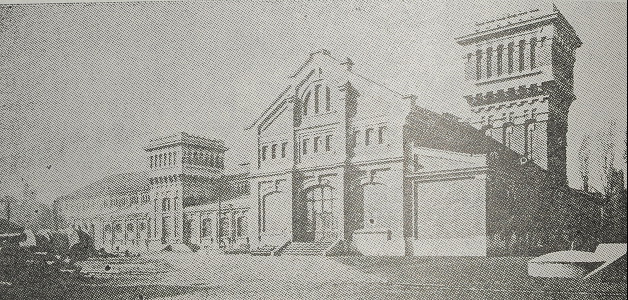

The Gas and Power Society builds between 1907–1908, on their own site in Filaret, in cooperation with Societé du Gaz pour la France et l’Etranger and following the project of the French engineer, Alin Lonay, the first communal power station of Bucharest. In 1924, the shares of the society were bought back by the city, after which energy production multiplied.

The initial building, displaying romantic apparent brickwork architecture, placed perpendicularly on Candiano Popescu Street, is extended with a building made in the same style and placed parallelly to the street. This is, in its turn, extended in stages (reaching about 120 m) along the raise of the consumption and the need to install larger units. One can notice the elegance of steel girders, the high degree of natural lighting of the halls, as well as the mobile bridge, still functional today.

The station was abandoned in the 70s and emptied of all installations. The historical building of the station is today the property of the Electrica Serv Company and used as garage for intervention cars. Having no divisions, it could be used for other functions as well. A series of studies and graduation papers analysed the opportunity of turning Filaret Power Station, the most natural proposal being that to transform it into a museum of energy, as an extension of the nearby Professor Engineer Dimitrie Leonida National

Technical Museum.

This idea does not lack future opportunities, given the reactivation in 2003 of the initiative of the General Association of Engineers, the Romanian Academy, the Technical University and other bodies, to make in Filaret/ Carol Park a National Park of Science and Technics, in which the Technical Museum, extended and modernised, would be one of the main attractions.