Text: Alexandru Cristian Beșliu

Images: Carmelo Baglivo, BAN

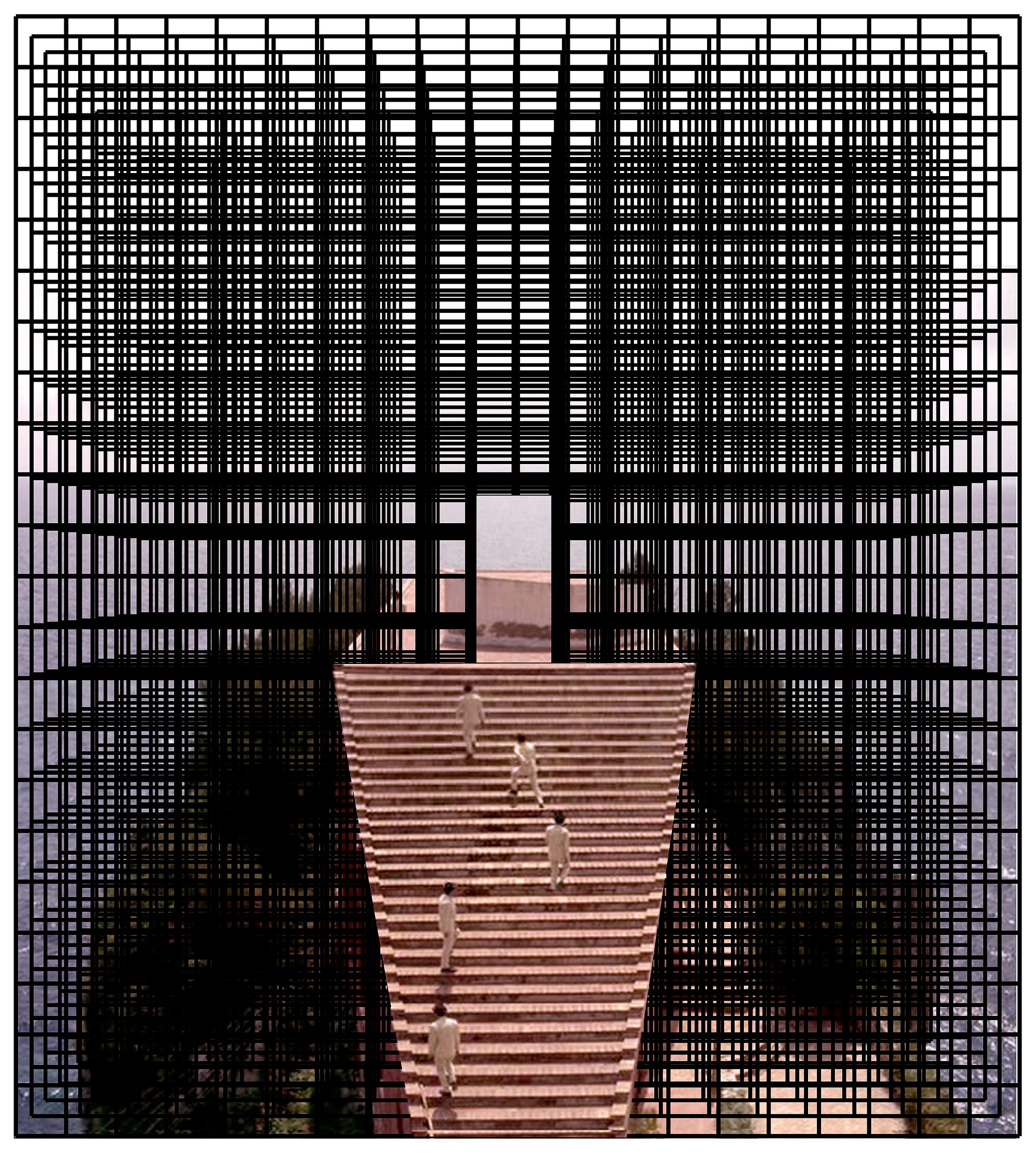

For Carmelo Baglivo’s generation, formed in the 80’s, the architectural representation, the image, has become a fundamental ideological pursuit complementary to the project, yet a willfully autonomous one, free from the constraints of immediate realization. Carmelo’s collages and drawings capture the disorientation of someone who dares to interrogate the legacy and memory of modernity, of its “fathers”, its masterpieces and its myths.

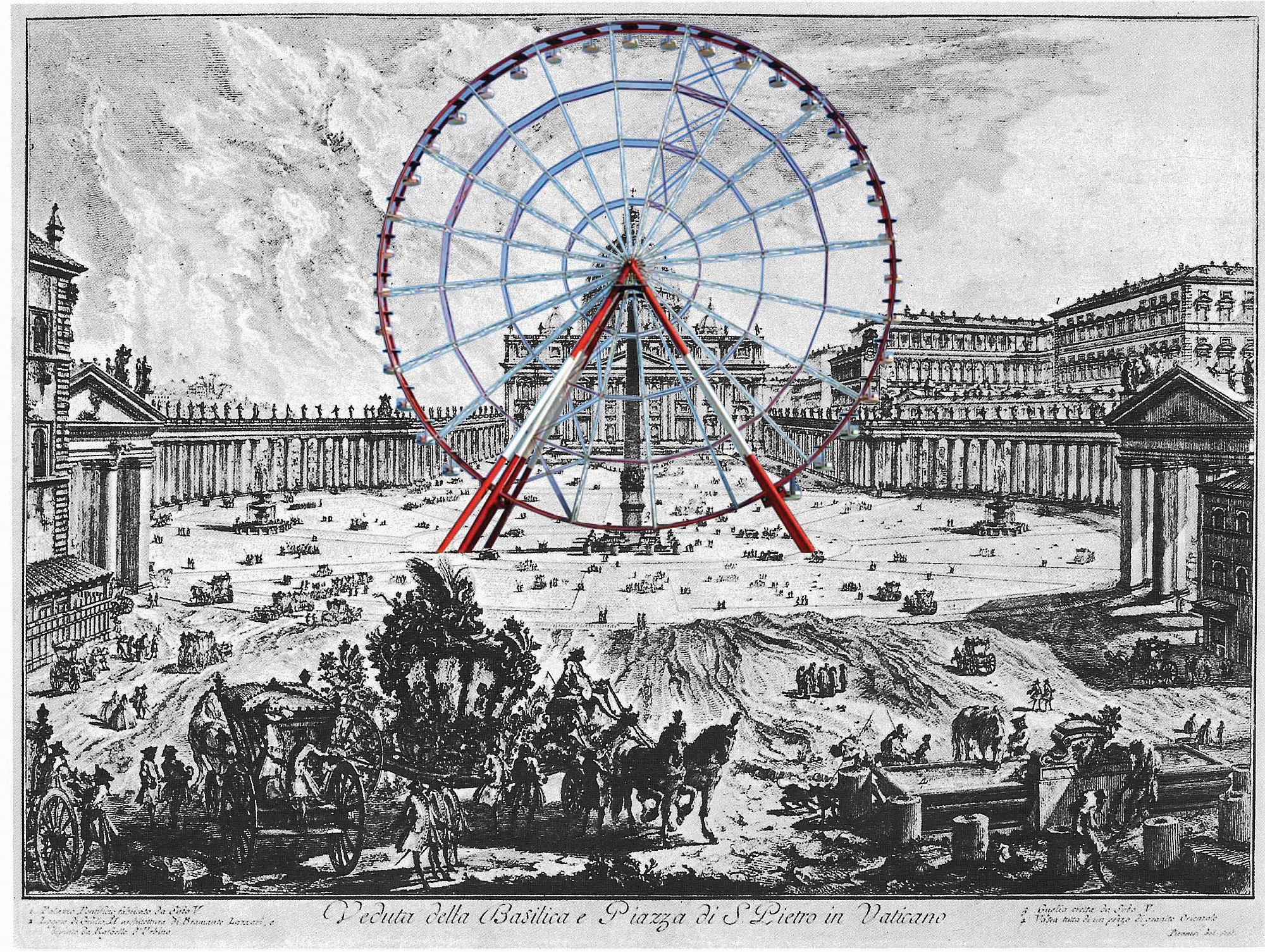

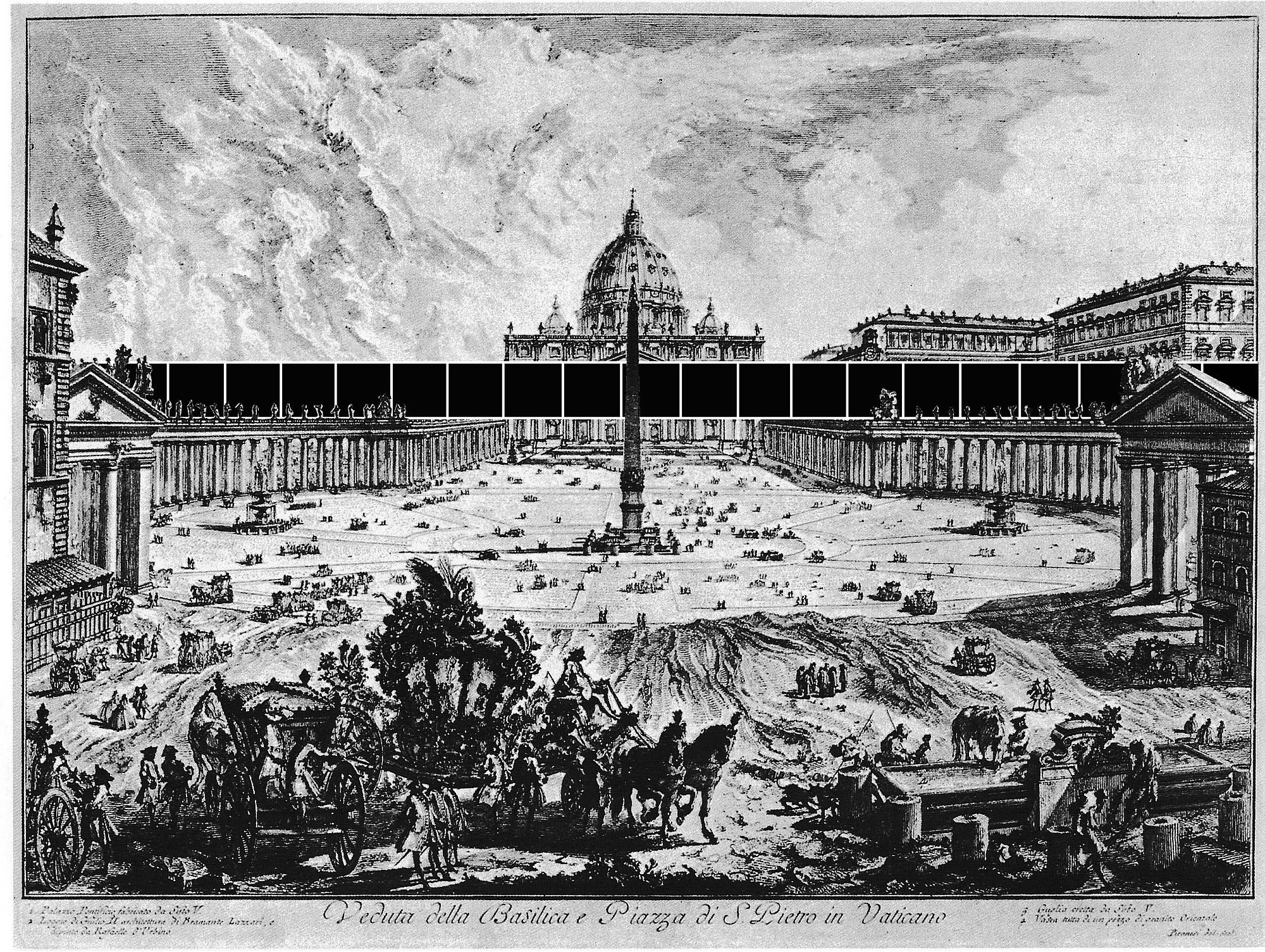

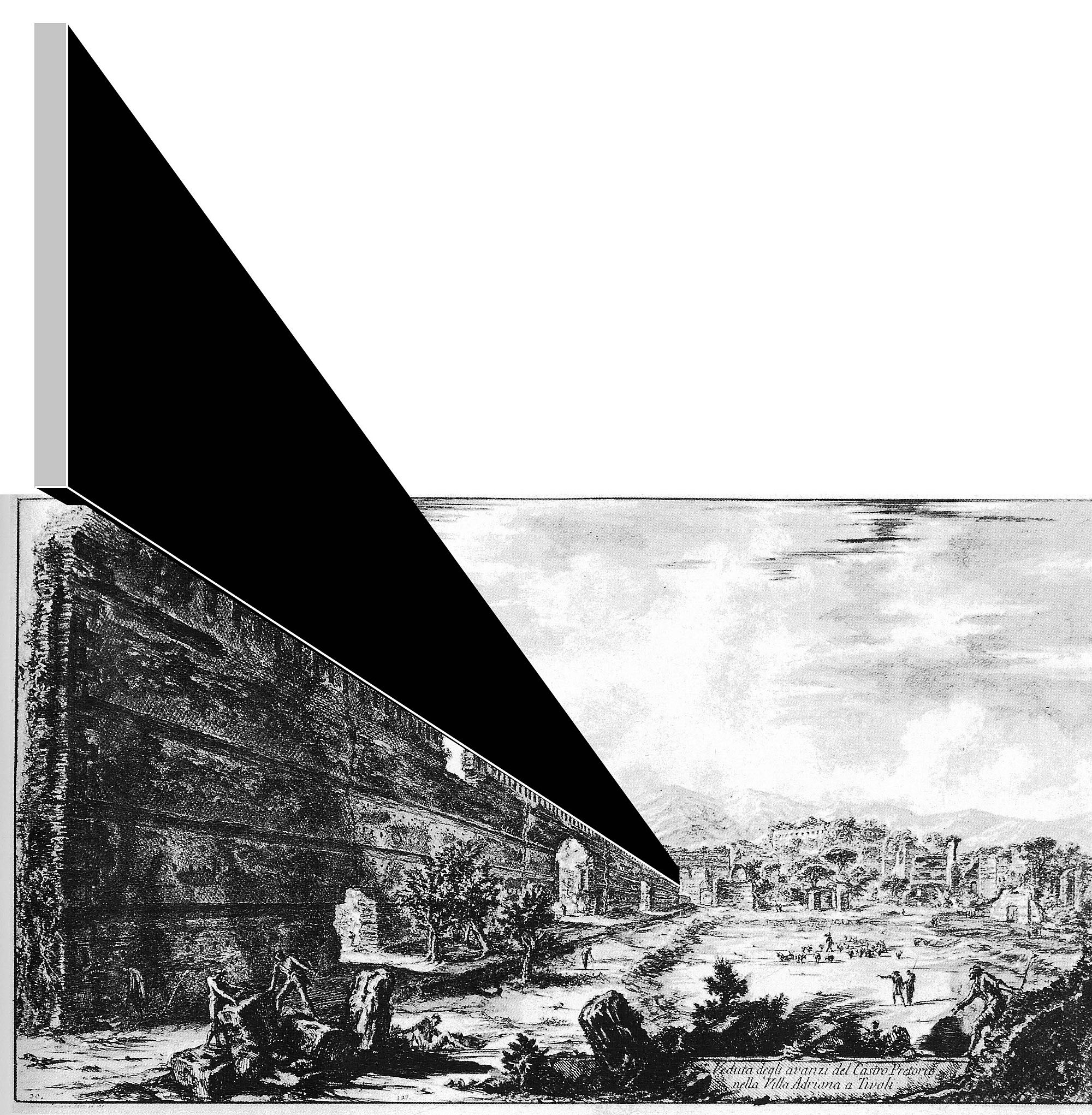

Being modern today, Carmelo Baglivo thinks, means being more inclusive, taking in a maximum of parameters in the design process and even beyond it. Hence the misalignment with the International Style’s formally, and ideologically univocal “recipe”. The recurring motif of our dialogue has been the act of “putting in crisis” as an essential approach towards contemporaneity (in architecture, city, politics, society, etc.). In his case, this push towards crisis uses image as an indispensable instrument. His images are a re-writing or, rather an over-writing, of the preexisting/precedence (from the Via Appia to the modernist masterpieces).

His images are autonomous and must not, by any means, be directly connected to the project; at most, the image can offer a reading key, it can slightly touch or ideologically overlap the project, but cannot, in any way, provide a “recipe book”, or a catalogue… the purpose of the image is not to bring out a solution, but rather to persist in a continuous doubtful quest; it lies within this narrow strip of uncertainty. Speaking of representation, it is the image which creates a cautious oblique gaze that ignites the crisis.

Although they may superficially seem so, his images are in no way utopian,. As he states in “Disegni Corsari”, utopia is obsolete due to the immediacy of the future; considering the fact that, paradoxically, the future is lost, utopia has rather become an instrument of the past.

Carmelo Baglivo’s approach places the entire history of architecture on the same horizontal plane; systematic doubt brings into question the contemporary crisis. In this way, he reintroduces critical thought in the foreground of Italian architecture. The vast abstractly-reticulated territories that devour everything from landscape to city and architecture, or the imaginary rooms that settle inside the Imperial ruins, are neither dreams about the future, nor actual projects, but icons of a way of being a modern architect today: not by means of an immediate reference to a modernist formal repertoire, but by being modern in spirit.

We can spot two main architectural roots for Carmelo’s representations. However, his passion for art in general, and cinematography in particular, also infuses his images.

One of these main strands is: the Neoclassicist architect, engraver and “rebellious child”, Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Piranesi represents an idea about the city and architecture as a living object, an artifact whose potential is continuously enhanced by successive over-impositions… a continuous over-writing. His work serves as a narrative instrument for Baglivo, a basis to graft the scenarios of his collages on.

The second essential reference are the “radicals” of the 60’s (Superstudio, Archigram, Archizoom, Hans Hollein etc.). Architecture as the “theater” of human activities, and a similar “post-postmodern” legacy, are also reasons for his admiration for the younger Rem Koolhaas. Baglivo shares his interest in the new millennium and the discourse on program-function-form at the scale of the city and its architecture that was only beginning to suffer from “bigness”.

The two strands (Piranesi and the “radicals”) do not come as reiterations of old ideas, but as critical instruments for new interrogations, a new thought about architecture and the city, one of consolidating and enhancing/recovering the pre-existence through re/over-writing the precedent.

Carmelo has a rather cyclical way of being both a scholar and a practitioner. He teaches for 3-4 years in a certain place, working with the students slightly tangential to his own research topics; after that, he spends as much time to tackle work commissions in his architectural studio, he enriches his research through images and texts and works on architecture competitions.

Regarding the social media, Baglivo says this medium has helped his images and research to become known to the general public, his rather introvert character notwithstanding. He’s a bit tired of the internet now, and less atuned to what Bart Lootsma was referring to as “the instrument that managed to bring architecture into mainstream media and get it closer to lifestyle, fashion and pop culture”. However, he has a considerably active fanbase on two of the most popular social-media platforms, and that is no small feat.

We chose to present here two Roman projects from BAN architecture studio (Carmelo Baglivo, Laura Negrini): the interior design for MACRO ASILO museum, and CARACALLA REBIRTH, a vision for the reuse of Carcalla’s ancient thermal baths complex. Although on two completely different scales, both projects stand for the same thought about architecture as artifact containing human activities/connections and about its grafting on a certain preexistence.

MACRO ASILO – Designing the Hospice[1] Museum

Macro (Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome, Studio Odile Decq, 2007) is an institution that changes the paradigm of the conventional museum space, becoming an eminently freely accessible public place, where artists are invited to exhibit themselves, to move their workshop within the confinements of the museum.

The two years preparation and interior design was born from a close collaboration with the museum’s director, Giorgio de Finis. The museum connects two streets (Via Nizza and Via Reggio Emilia), becoming a public space on three levels, from the foyer to the terrace. The main room of the museum has been organized as a slightly elevated piazza/stage (a place for gatherings, events, concerts, theater plays, etc.), surrounded by strange objects that appear to be amorphous archaeological remains, artifacts of a dead civilization. These weird fragments made from a dense polystyrene coated with resin can be grabbed/moved/turned to be used as chairs, tables, or any other type of object depending on the visitor, or the moment/scenario.

The congress hall houses the only fixed element of the museum, the wall-gallery that makes up the so-called “permanent collection”, a work of art in itself; further on, one arrives in the room dedicated to Rome, a room that has a big table in the center, a perfectly horizontal mirror-plane engraved with the plan of a passing Rome that changes according to that which it reflects – the image of the great urban laboratory. The twelve plan fragments are made form the same polystyrene and are interchangeable, paving the way for an infinite number of possible hypotheses for the eternal city.

From the room of Rome, one goes to the first floor, in the room of words, a place resembling a primary school classroom, with seats, tables and a writing blackboard.

The moving pieces of furniture are made up from wooden panels fixed on a metal substructure, they are decorated with cutout elementary forms, and are also provided with sets of wheels. From here, one can further go to the lecture room and, thereafter, the artist’s workshop.

The 5x5x2.5m room is inhabited by the artist for as long as he needs to produce his artwork. The design had no actual collection in mind, concentrating instead on the creation of a shelter forn the birth of the artwork.

The project, in its entirety, has brought about a transformation of the museum through simple elements that make it permanently available for multiple scenarios.

CARACALLA REBIRTH – Designing the reuse of the ancient monumental thermal complex of Caracalla

Caracalla Rebirth is a hypothetical project presented as part of the Architectural Biennale in Pisa (opening on the 21st of November 2019). The main theme of the Biennale is water, “Tempo d’acqua” (The Time of Water) ; BAN studio’s project aims to reinstaure in Rome the lost function that public baths had in Rome, namely community spaces. The case study is a building suspended over the ruins of Caracalla’s baths.

Two lateral corridors marked by large openings of elementary geometric define a regular space; it is comprised of a sequence of pools, green spaces and public facilities (sports halls, libraries, shops, etc.). Similar to the adduction system from ancient times, the water is collected and distributed along the perimeter.

The new is reborn and rises from the ashes of the old; new and old coexist in one horizontal plane determined by the purpose of reviving a long forgotten way of living and experiencing the public space.

Bio

Carmelo Baglivo (Rome, 1964) studied architecture at “La Sapienza” University in Rome. In 1998, alongside Luca Galofaro and Stefania Manna, he founded IaN+ architecture studio. The studio became recognized through important distinctions.

Since 2015, Carmelo has been part of BAN – Baglivo Negrini Architetti (alongside Laura Negrini).

Carmelo Baglivo’s drawings and collages have been part to several exhibitions, the more recent ones are: Cut ‘n’ Paste: From Architectural Assemblage to Collage City, curated by Pedro Gadanho at the MoMA in New York; Innesti (Graftings), curated by Cino Zucchi at the Italian Pavillon of the Biennale of Venice 2014.

He is currently a visiting professor at the University of Genova, and was previously invited as a scholar at the University of Architecture in Ferrara (2008-2012). Among his more recent publications are “Disegni Corsari” (Corsair Drawings – with Bart Lootsma, Emilia Giorgi, Piergiorgio Frassinelli and Luca Molinari, 2014), or “Atlantide” (Atlantis – with Carlo Prati and Beniamino Servino, curator Giorgio de Finis, 2016),

[1] From the Italian word ”Ospitale” – In the sense of the latin word hospitium – settlement/shelter, hospitality