Text: Paolo Zermani

Foto: Stephane Giraudeau

Fifty years away from the Second Vatican Council and its request to build a new Church, it is best to remember the shots where, in 1950, Roberto Rossellini chooses to place the happenings in his movie, “Francesco giullare di Dio”, on the street climbing up towards Sovana, in front of the church, in one of the most important scenes of his movie dedicated to St. Francis.

The director emphasizes the arrival of Saint Francis and his brothers who, walking up the street barefoot, reach the village, through the Etruscan gate, to reform the Christianity in crisis. Their faith, practiced among people, outside of sacred spaces, is manifested as a fracture, meant to guide man’s time towards a time of eternity, in danger of being lost.

The street is the place and, at the same time, the means of implementation, from matter to spirit, from mundane to absolute, of the soul discipline, establishing a rule which is based on and which will be forever based in the Franciscan story, on a few fundamental points.

Similarly, in 1927, in the first chapter, called “The face of an earth” of his novel “San Francesco”, Romano Guardini, fully dedicating himself to describing the architectural atmosphere and deriving from it the meaning of Franciscan living, noted as decisive the material context into which the figure of the Saint was built, ever since his youth:

“From the slopes of the Apennine, if one goes down towards Tuscany, houses appear scattered as smooth and clear cubes. If one moves to the Perugia side, it is as if one crystal towered atop another. Architecture is almost immediately perceived, from a first glance; yet this is just the beginning. Architecture seems to be fully related to the measurements of the human body, to the arch of the forehead, to the opening of the chest, to the being which feels and lives it, through space. One is thus permeated through an elementary force by the way this rigour acquires shape and strata.”

The saint emerges, is born, in his complexity, from the structure and the internal and external shape of the landscape. Hence the fundamental designation of the crucifix as means, but also labour of rebuilding the ruined churches, before completing the mission of the spirit, and the urgency of engaging the body in the name of the material missions and works as a nearly initiation practice, for the spirit.

As San Bonaventura was saying in “Legenda Maior”: “in fact, through and by the grace of the Divine Providence, the Saviour would lead it all, so, at the start of the Order, before preaching the Gospels, it rebuilt three churches. This was just a consequence of the fact that it had learned to gradually give up the material things for the spiritual ones, or the minor ones for those that really mattered, but also that, through sensible things, the made, built things, he could have mysteriously foreshadowed the many things he could have go on to accomplish.”

The identification of the Franciscan way of life with everything matter, physical effort and material substance, is so grounded that Giotto, in his frescoes describing the life of Saint Francis, depicts the scene in which, inside the ruined church of Saint Damian, the Saint receives the instructions of the crucifix, a crucifix that was, even at that time, an artefact both ancestral and symbolic, and actual and physical.

These sequences that are deeply rooted in memory and in the history of the place, but not alien to the present, accompanied the project for the prayer chapel made for the Florence visit of Pope Francis, for the Italian Ecclesiastical Convention of 2015.

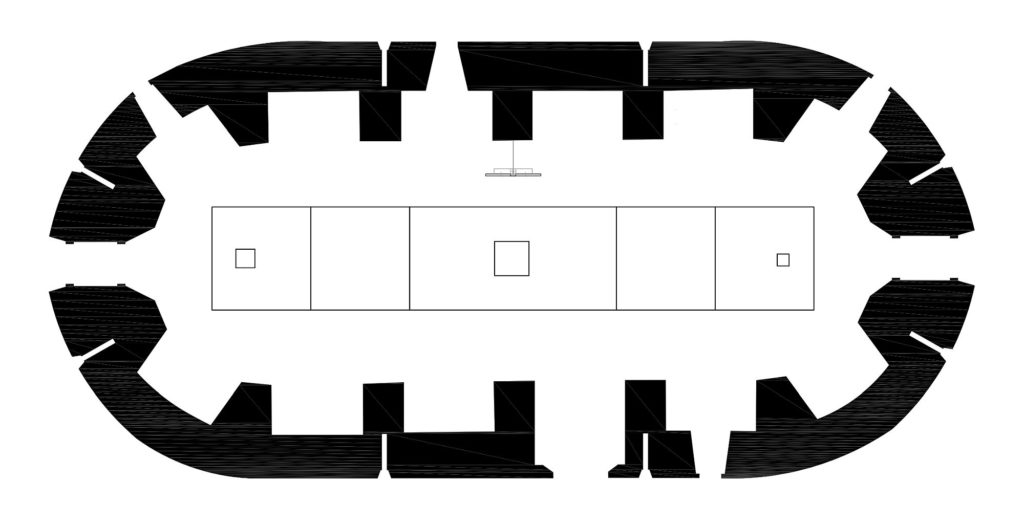

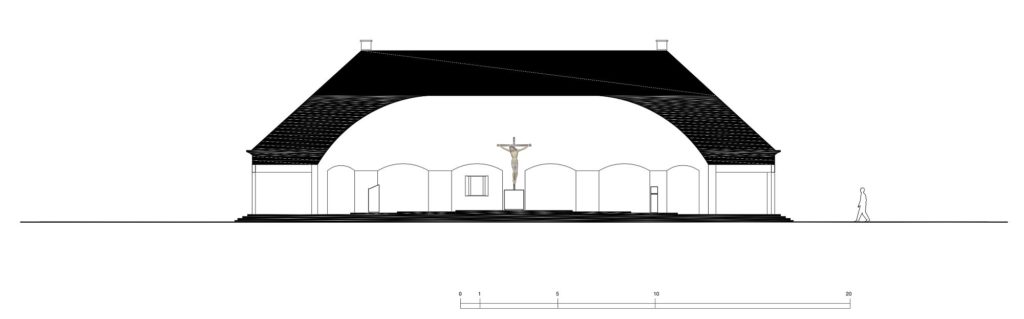

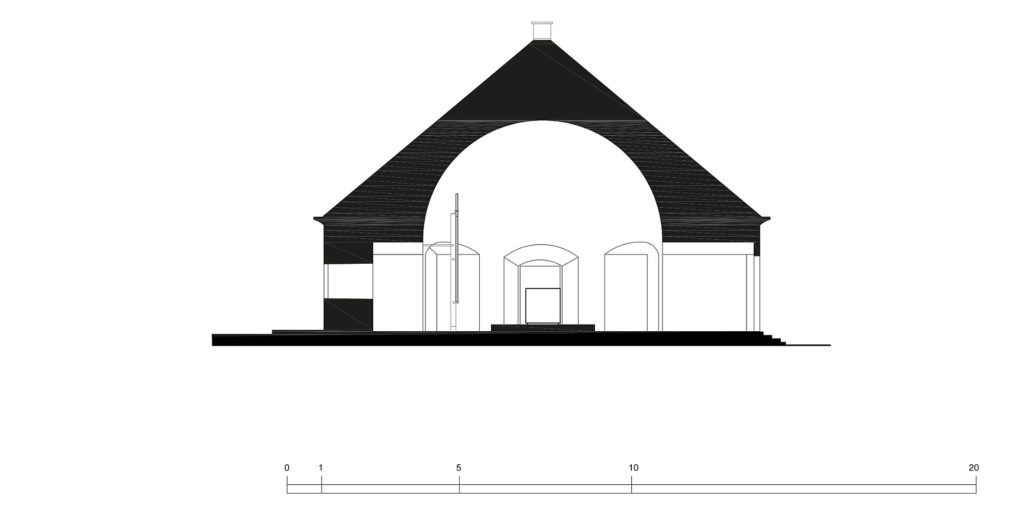

The sacred space of the chapel is placed inside the old powder room, respecting its space, with all its three entrances, two on the longitudinal axis and one on the transversal one.

The generating idea pf the project is that of a street along which there is, at the centre, detached from the horizontal plane, the altar, while, on the sides, close to the openings, the pulpit and the tabernacle rest are placed, both illuminated directly from outside.

*Plans & sections

A path, therefore, a street, marked by three milestones, absolute points conferring it its own measure.

Next to the central path of the chapel, suggested in the old room, at its core, placed as an indicator, on a metallic support placed next to the altar, but on one side of the road, there is an old crucifix of Baccio da Montelupo, coming from a Florence church.

Both the path/street which crosses the chapel’s longitudinal axis, and the altar, the tabernacle support and the pulpit, are made of travertine.

Info & credits:

Architecture: Paolo Zermani,Eugenio Tessoni

In collaboration with: Gabriele Bartocci, Rocio Fernandez Lorca.

Delivery: 2015

Client: Italian Bishops’ Community