Reporter: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Photo: Arjan Bronkhorst, Fred Erns, Ștefan Ghenciulescu, Georgiana Ghenciulescu

The title above is not a journalistic metaphor, but is in fact the name of Amsterdam’s oldest museum (after the Rijksmuseum), established in the 19th century in a very special 17th-century house: the home of a rich bourgeois in Amsterdam’s golden age, which has a church as its culminating and hidden point. This is not a domestic chapel, but a public church, complete with an altar, pulpit, organ, upstairs gallery, vaults, statues, benches and seating for about 150 people, and so on: a unique example of a public space and sacred place, knowingly integrated into a civil dwelling.

What is the church doing in the attic?

Well, it was hidden there, or should we rather say, it was concealed. As we very well know, 16th and 17th century Europe was torn apart by the religious disputes due to the Reformation. Depending on how they had or gained power, Catholics would persecute Protestants, and Protestants would persecute Catholics. And violence would vary from long and bloody wars (such as the Thirty Years’ War), to massacres like the night of Saint Bartholomew, or to legalized persecutions, ranging from prohibiting to severe limitations to the exercise of faith. Architecturally, we could also mention the clandestine chapels and the so-called priest holes, hiding places in many aristocratic homes in England. When caught, death (possibly by torture) was one of the usual punishments.

The great exception would be Transylvania, at the margins of the Western World, where the Ottoman danger required solidarity, and where religions elsewhere exterminated ended up officially living together, and, in a wholly different context, there would also be the Netherlands, and especially the City of Amsterdam. The welcoming of Spain’s deported Jews is already famous, but it is less known that, although all Catholic churches had been seized and the Mass was prohibited, the city’s administration was tolerant of the practice, as long as it was not done openly. The reasons of this relative tolerance are complex, ranging from a trade culture’s pragmatism, to the openness of a sailor nation, to self-management instead of being led by princes, etc., etc.

Thus, several churches sprang up in houses. The analogies with other eras are not numerous, for we are not speaking of absolute clandestinity, but rather of a kind of tacit agreement, a somewhat milder persecution and an accepted modus vivendi. I can think of, for example, the Orthodox churches built in Ottoman-dominated Bulgaria, without spires, at the scale of a house or even a hovel, usually half-buried.

The church was built in 1663 in the high attic of Jan Hartman’s house, a rich German merchant. It functioned as a church until the late 19th century, when, thanks to the liberalization of religious denominations in the Netherlands, numerous Catholic churches were built. But it was preserved and religiously cared for by representatives of the community, and it quickly became, as I was saying in the beginning, a museum.

Today’s image is owed to a powerful intervention: the building of a structure, across the lateral street, was completed in 2015. The new structure (architect Felix Claus) has the reserved scale and image of an archetypal Dutch house, providing contemporary, white and clean spaces on the inside.

*left: the original house and the 2015 extension; right: looking from the museum extension to the old house

*left: the original house and the 2015 extension; right: looking from the museum extension to the old house

This is the point of access, and here is where the shop, bookshop, cafe, conference space, elevator, etc. are also hosted, as is the exhibition of a series of precious objects, of the model and panels showcasing the house’s history. The basement connects the two buildings. This way, the old house is spared from supporting (yet very necessary) functions, but also from the obligation of having an exhibiting space. It thus becomes once again an in-situ museum, it exhibits itself, from spaces to materials and furniture, with minimum information and maximum focus on the place and on the histories.

*The 17th century kitchen

*The 17th century kitchen

I do not wish to make a description of the museum’s architecture, but I need to mention its fundamental character: the alternation between the large, precious, orderly, and bright spaces, and the small, crammed ones. This is not only about the annexes, but about the circulation as well. The house is a rich man’s one, but, totally different from palaces or other prestigious buildings, the pragmatism and obsession with comfort to the detriment of representation lead to the elimination of any impressive circulation (monumental staircase, galleries, etc.); of course, the limited available space, in the centre of a hyper-crammed city, also plays a role here. The stairs, the hallways, are minimal but, as is the case of many examples of quality architecture, through the surprise of sudden passages from compression to exaltation, they somehow offer even more prestige to the major spaces. The Great Hall, for instance, is a good example of domestic Nordic Classicism, with its rows of large windows turning into a sort of protomodern band window.

*The living room

*The living room

The main bedrooms are also remarkable, adopting the formula of a room-within-a room: the beds, as everywhere in the house, shape up as ‘sleeping closets’, niches cut out from the larger spaces.

*Bedroom

*Bedroom

The spatial richness in such a limited frame is amazing, reminding me of Sir John Soane’s house in London (another quaint house, combined with a workshop and with exhibiting architecture).

The last closet-bed is practically at the end of the way leading up to the church. The faithful would climb the narrow dark staircase in a line, passing by one of the house’s most intimate rooms, to open a discreet door and to enter the sacred, bright, and noble space.

©Georgiana Ghenciulescu

©Georgiana Ghenciulescu

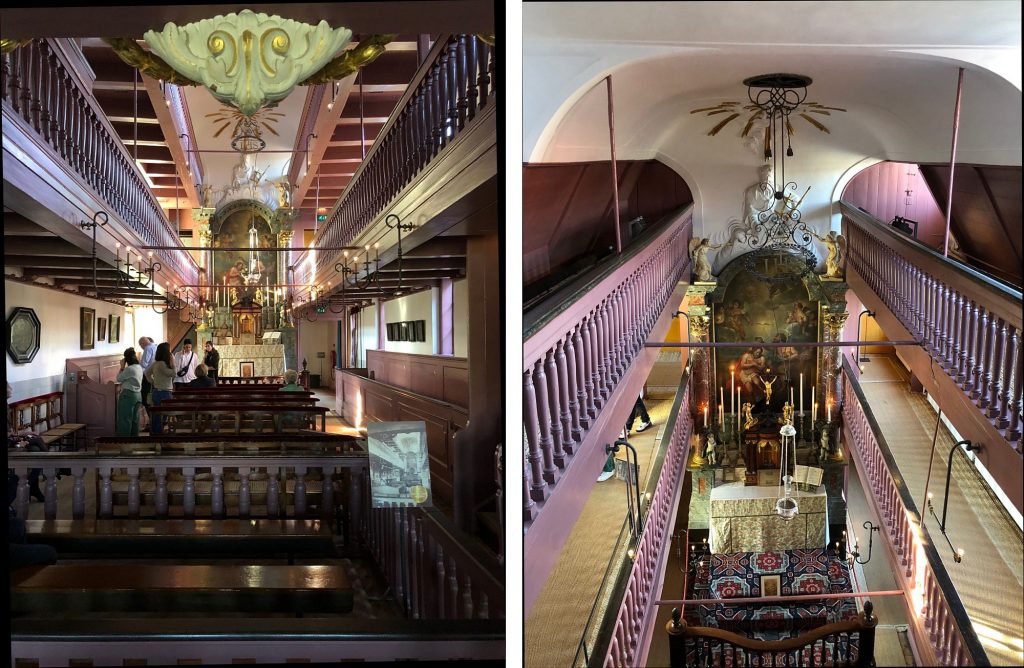

The church itself is an engineering and architectural tour de force. There are no props down the middle, the structure was thus altered to not destroy the absolutely necessary unitary space.

*The church ©Georgiana Ghenciulescu

*The church ©Georgiana Ghenciulescu

The stands surrounding the grand central space are in turn accessible via very small staircases. The necessary rooms for the mass, the sacristy, etc., are located in the area behind the altar, and are connected to the circulation in the rest of the house.

*Confessional

*Confessional

Exiting the old house, you may perhaps linger for a bit in the exhibition in the new building. And you may perhaps think of one of the museum’s fundamental and explicit topics, arisen from the combination, so particular here, of domesticity, intimacy, and the place of a community: freedom of religion and conscience but also, in general, the quiet resistance and then the tolerance, the respect and the cohabitation. Also from an architectural perspective.