A modest gesture, yet one capable to change the way one experiences the church and its yard. The restauration brings an object that served the community back into nthe life of the village and its surroundings.

Text: Cătălina Frâncu

Photos: Vlad Pătru

Introduction

Restoration is a difficult subject. First of all, the very term makes one think of historical monuments, protected areas, churches, fortresses, and other “untouchable” architectural objects. Both architects and owners often avoid them. However, we live in a world increasingly oriented towards the reuse of built structures as a resource in the fight against climate change and waste, raising questions about best practices when intervening on a site with a strong heritage.

One such site is the ensemble of the fortified Evangelical church in Curciu, Sibiu County, Romania. This county is already known as a hub of cultural centres in the Saxon area, places we’ve written about in At Work At Home book and in the magazine. Here lies one of the largest communities of city dwellers who have moved to the countryside, surrounded by a sea of houses abandoned during the Saxon migration in the 1990s, leaving behind a vast heritage of buildings and life stories, communities struggling to survive today. Their proximity holds promise.

In Curciu, as in most Saxon villages, the figure of the “key holder” appears, embodied in Mrs Dana, a teacher in the commune. The responsibility for the entire ensemble falls to her in the absence of the Saxon community, which only returns to the village once a year. The church in Curciu was chosen from three possible intervention sites, and one of the main factors was the willingness to continue caring for the place after the architects’ intervention.

Restoration is Architecture

I was curious to find out how such a project comes about. It’s the kind of studio project that would barely get a seven (out of ten) because it lacks enough architecture. And yet, it seems that from now on, projects of this kind will become more and more common and sought after.

Since the village has no guesthouse, the Saxons no longer have anywhere to stay when they return, and tourists cannot find accommodation nearby, the Fortified Churches Foundation commissioned Modul 28 to create some accommodation spaces in the tower, chapel, and bell-ringer’s house, with the dual purpose of working with a team specialised in interventions on historical sites and launching a new, young team through a rare project in Romania.

Modul 28 intervenes on the space with the weight and conviction of architects who understand design beyond new construction. The ensemble of a fortified church in a depopulated Saxon village is as complex a design opportunity as urban planning: parametric studies, understanding the space, valorising Gothic forms, and architectural decisions that must balance the budget with the purpose of the space. Here, a valuable fresco was discovered, dating from before the Lutheran Reformation, which brings a reasonable number of tourists every month.

Above all, the design team sought to understand what the English model of champing (short for church camping), where you can rent a room or a bed for a more or less affordable price, might mean for the Curciu ensemble. However, for the Romanian diocese, the concept is still distant, so the spaces the architects intervened on are part of the fortification wall, not inside the church itself.

The Chapel

The architects emphasise the delicacy with which a professional must approach such a spectacular space, which they did not alter at all.

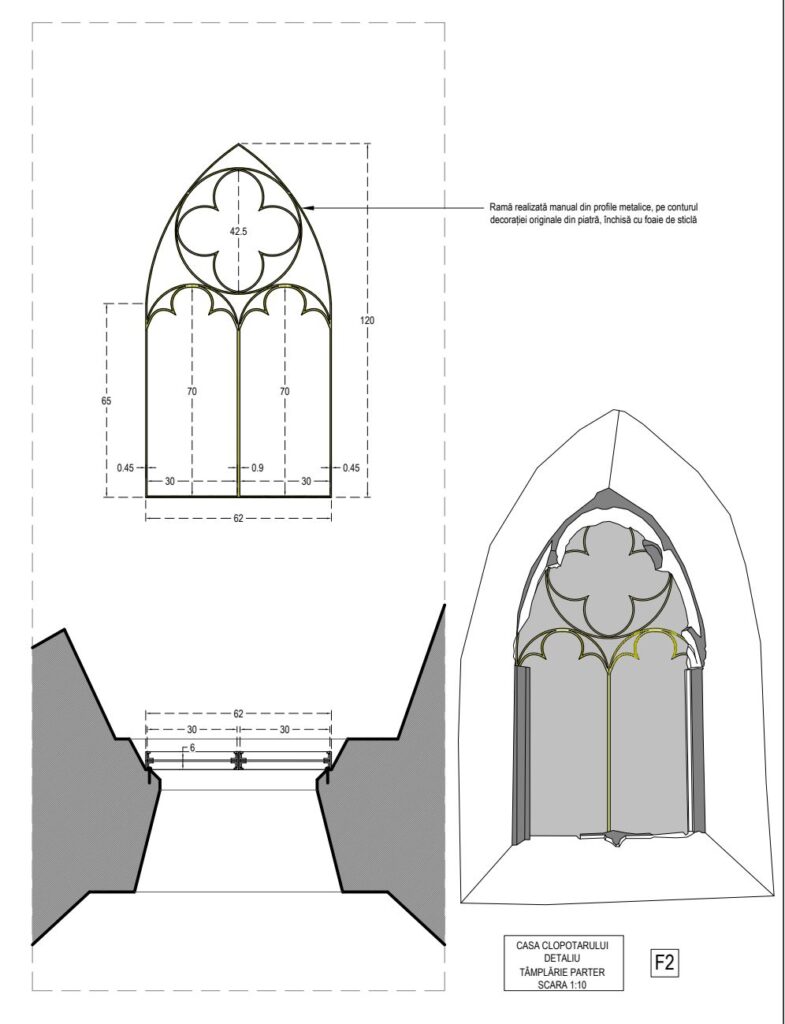

The only additions were the installation of non-sealed metal windows and tiling the roof. These two delicate gestures allow the space to be used only in the warm months, as it is impossible to heat during winter — sealing it without altering the historic atmosphere would have exceeded the project’s budget. The stone window frames in the chapel were cleaned, secured, and conserved.

The entry through the portal to the chapel’s three windows presents an iconic image of Gothic style, often referenced in specialist literature, making it very important to preserve this image to avoid altering its historic character. The parametric study also revealed the existence of a collapsed vault, leaving the roof’s intrados exposed. The remaining elements were conserved, and to soften the harshness of the stone, the chapel was given a wooden floor.

Archaeological excavations around the chapel revealed a staircase leading to the ossuary. In the restoration intervention, the steps were preserved, and the ossuary was covered with a wooden slab.

This raises one of the important discussions in restoration: what are the project’s priorities? Preserving the shape of the space or using it year-round? What do you choose when the two cannot be achieved simultaneously? Because the ensemble dates back to the 15th century and Gothic heritage in Romania is scarce, preserving the authenticity of the windows and roof was the priority.

The Tower

The western side of the gate tower, explains Andra Nicoleanu, co-author of the design concept, hosts a Gothic painting still visible today, and its positioning indicates changes in the volume’s shape over time.

In the tower, where the brick was exposed, the architects decided to simply repoint where necessary, leaving the material visible.

The Bell-Ringer’s House

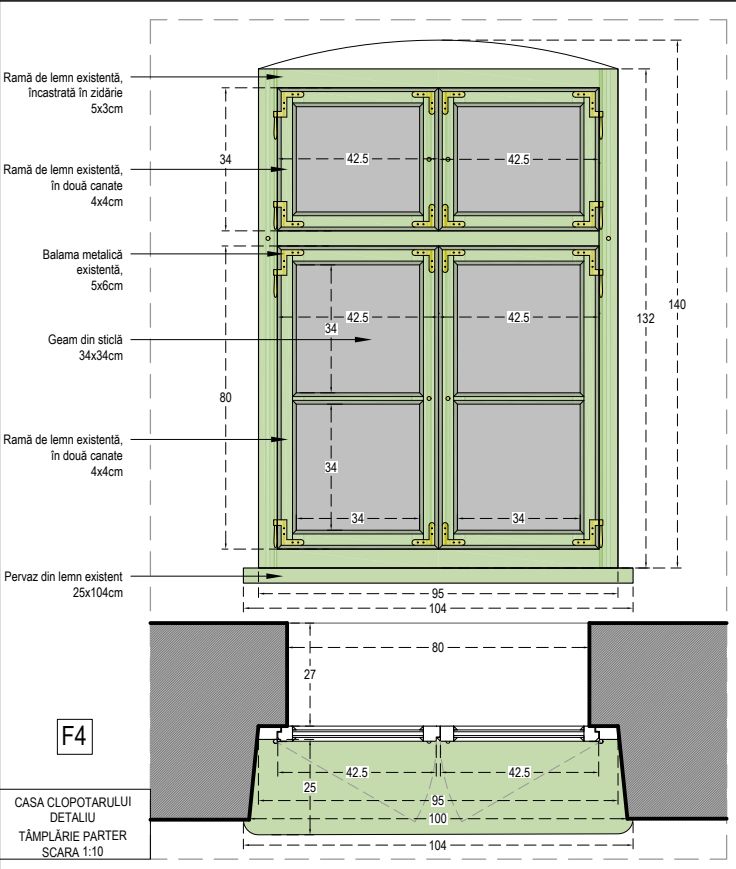

In contrast, the plaster layer in the bell-ringer’s house was relatively new, so it was redone without hesitation. Here, too, is the kitchen and two accommodation spaces: one on the ground floor and the other in the attic, accessible by a newly built staircase.

Above the kitchen, also in the attic, are the technical areas. From here, access is provided to the bathroom, and the everyday life of guests unfolds during their stays.

The Toilet

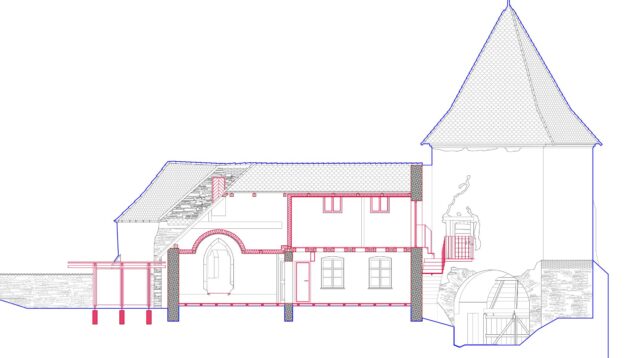

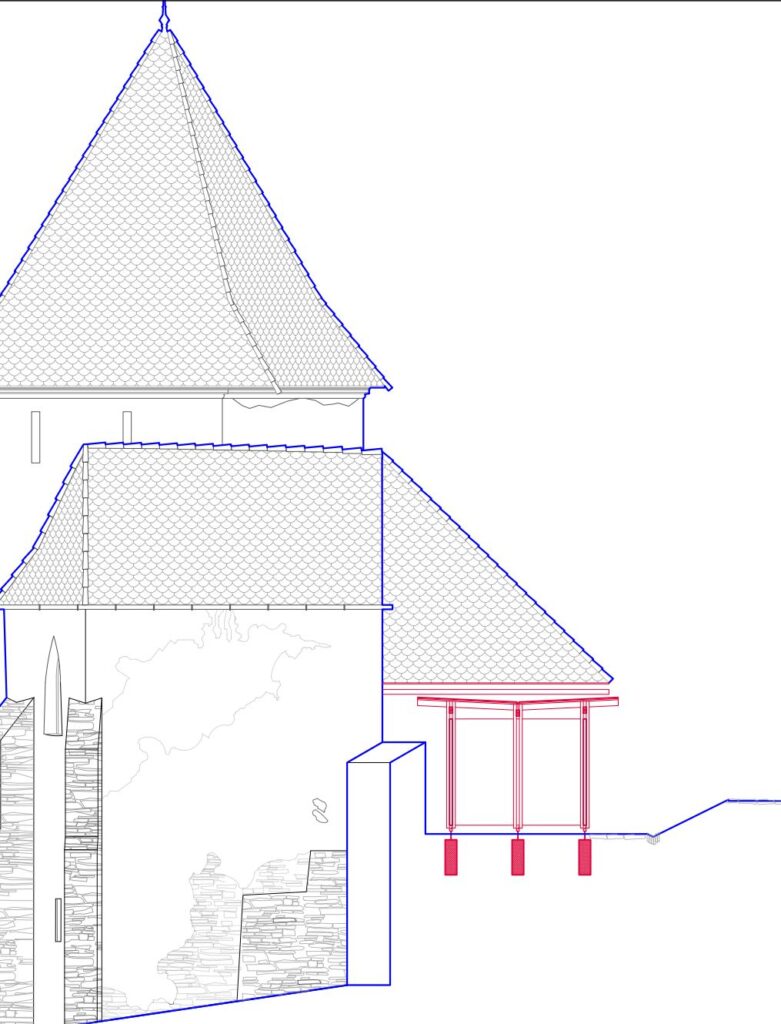

The house and tower were transformed into accessible and functional accommodation spaces thanks to the only two constructions designed: the external staircase leading to the attic and the entrance to the tower over the gate, and the toilet.

As is often the case in such situations, the toilet became a sensitive point. Before the intervention, the ensemble offered tourists an outdoor toilet taller than the house’s eaves and the defensive wall, almost a landmark outside the ensemble. The new intervention, more modest and respectful, extends from the house and occupies the space between its outer wall and the defensive wall, keeping its height below the eaves.

The wooden structure uses thin, minimally sized elements supporting the roof in a vertical-horizontal structural arrangement, with a few restrained decorative elements in a herringbone pattern. Using a lightweight structure of natural wood shows a strong concern for preserving the clarity of interior spaces while also integrating harmoniously into the challenging context of a historic monument.

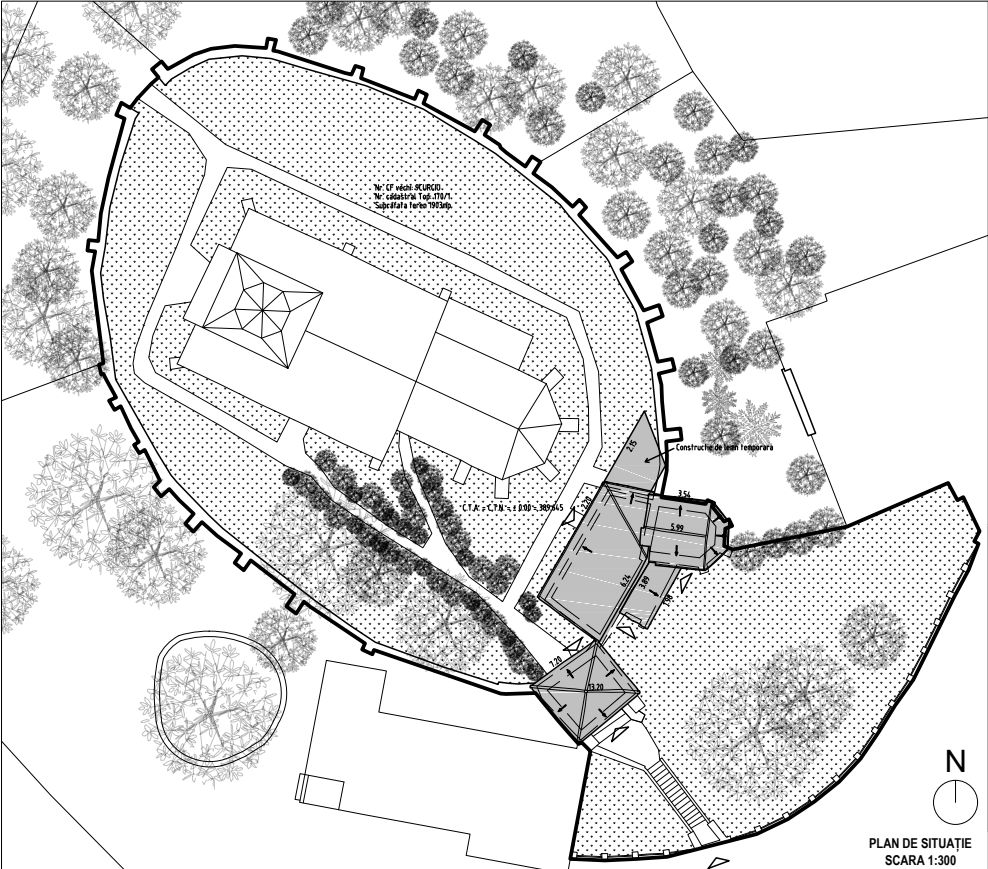

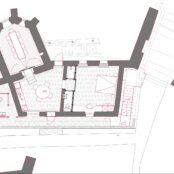

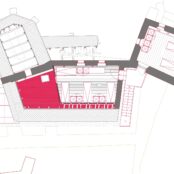

Plans:

Info & credits:

Architecture: Modul 28 – Tudor Pavelescu, Andra Nicoleanu, Robert Makkos, Vlad Ducar

Engineering: Level up Structure – Adrian Roșca

Structure Consultancy: ing. Gelu Mureșan

Installations: Carmen Stănescu

Historical Studies: dr. arh. Hermann Fabini, rest. Lorand Kiss, rest. Sidonia Olea, arheolog expert dr. Marian Țiplic

Execution: Domino Expert Construct SRL : Attila Galfi, Szilard Szenyes Imre Galfi

Metal Pieces: Sorin Prislopan, Denis Kapolnai, Mihai Biro

Furniture: Attila Szasz

Beneficiary: Fundația Biserici Fortificate: Philipp Harfmann, Stefan Spindler, Annermarie Rothe, Andreea Mănăstirean, Ruth Istvan