Intro: Modern by sound omission. The virtue of abstinence

Text: Cosmin O. Gălățianu

We make a note on the work seen from outside: it is clear that retrospection to the work, to the working, has a modernity of itself. In other words, the way the work is regarded, for instance the work of architecture, legitimises or not its modernity. Such a regard, a recent one, we may say, has twisted towards a type of architecture that is convenient (and here we mainly refer to the architects) by its implacable righteousness.

With Uwe Schröder, what seduces is the righteousness of a loyalty to the architecture project, its ordering nature and at the same time that which we may call the virtue of abstinence. It is under the sign of this desistance, however, that we will also repress our reflex of referring to German rationalism, Italian rationalism, the mid-sixties, Ungers, etc. because Schröder’s abstinence does not reside, we hope, in retrospection to a historical context as an artefact but, of all things, to the return to an inaccessible concept of origin.

We say abstinence because we are dealing with an architect who denies himself from the very start the interior need of composing, as a volt before self-sabotage, and seeks placement in an initial character of the project, in something pre-existing.

We may well state that, as we find most of his works in the same city (among which the one presented below), Uwe Schröder precedes himself. Lingering in one place is an instrument par excellence of understanding it, and the systematic plunge in the city’s spirit is fundamentally made through construction (therefore through re-weaving and completion).

*photo 2: Uwe Schröder – Haus Hundertacht, Bonn

*photo 2: Uwe Schröder – Haus Hundertacht, Bonn

This process of replenishment of the surrounding, through successive connections and simplifications in the fabric, like in the case of the axial co-existence of Haus Hundertacht, Haus Clement and Galerie und Atelierhaus, is unavoidably reflected on the interior spaces, conferring them, at the same time, the measure of things.

*photo 3: Uwe Schröder – Haus Clement, Bonn

*photo 3: Uwe Schröder – Haus Clement, Bonn

From the city that gets measure and limits to the square and from the interior courtyard to the cell of the house, the types of relationships between the constitutive elements, or between inside and outside are, essentially, the same. This is essentially due to the arresting reduction in the language of Uwe Schröder and this also opens the path to the fascinating total perspective:

To sit in unaltered squares, in ziggurat-type sections with successive equivalent withdrawals (or advances) or in single-window facades, is to deliberately but reasonably renounce adding anything extra. Any additional element would only weaken or even contradict the project.

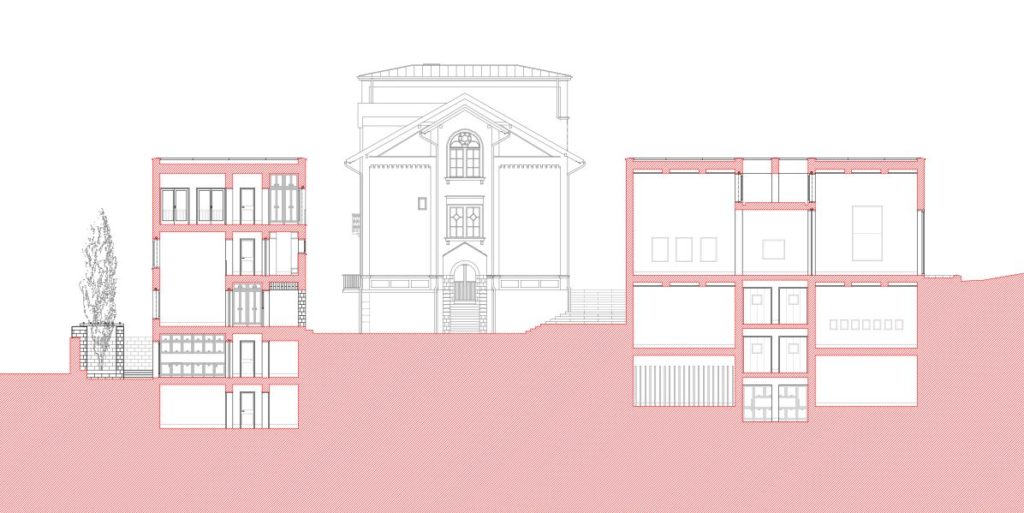

However, there is a dosing in this parsimony of expression, as wrell as a necessary and actually deserved compensation: inside, an architecture of the familiar takes over, one that works with rooms, halls, light, colour and texture, and that achieves human scale and a domestic character.

Galerie und Atelierhaus, Bonn

Text: Rainer Schützeichel

Photo: Stefan Müller, Berlin

* photo 1 (top): View from the street. Right, atelier-house, in the middle and recessed, the 19th-century sanatorium

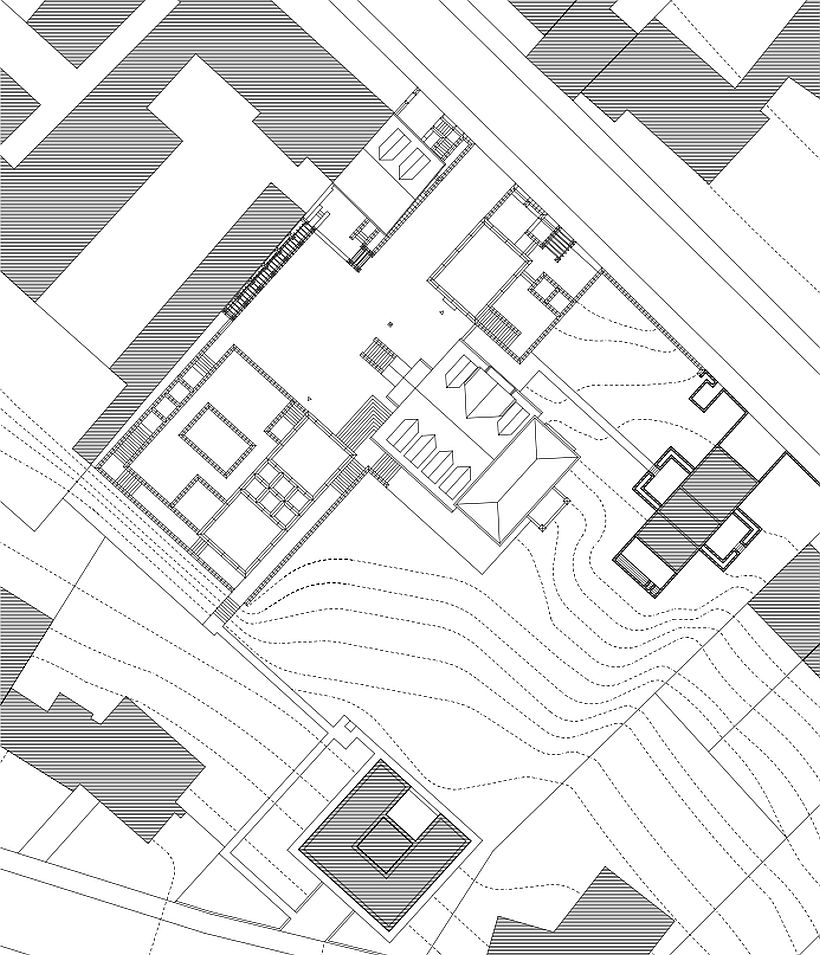

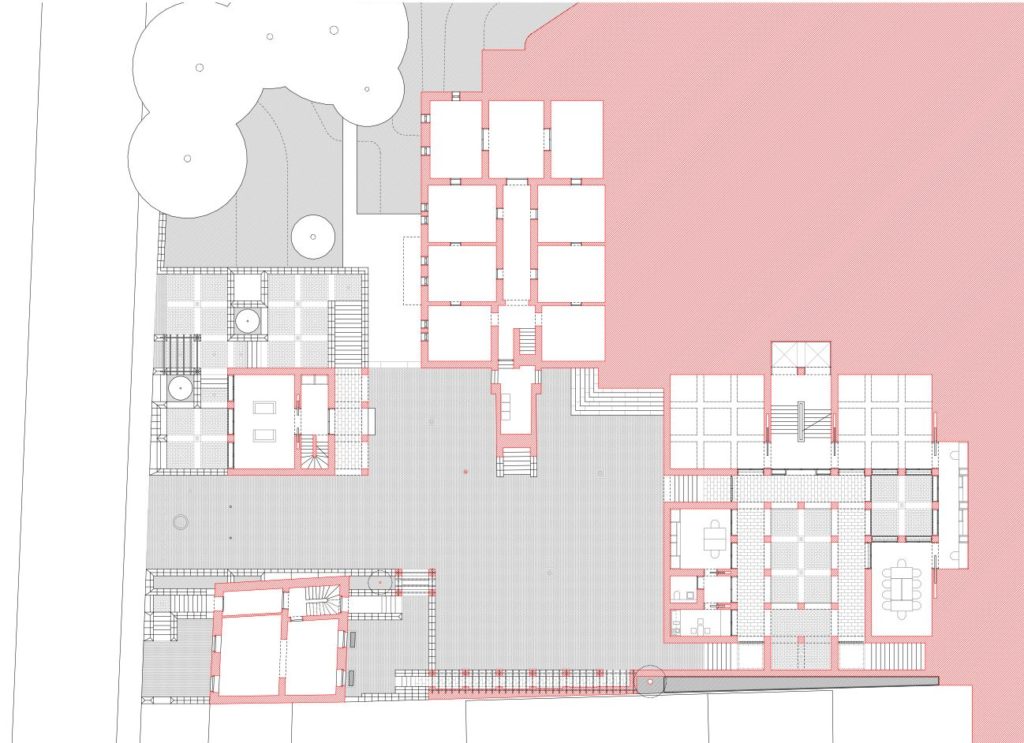

The gallery and studio buildings at Lotharstrasse make the complex structure of urban spatial types legible as squares, courtyards and semi-public and private interior spaces, as if seen through a magnifying glass.

The ensemble is situated in the direct vicinity of the Haus Hundertacht and is faced with the same heterogeneous context , to which it initially reacts by coding the exterior spaces.

While the neighbouring building reflects the idea of the city in the interior sequence of rooms, this pair of houses, which is extended by framing a 19th-century sanatorium at its centre to form a triad, represents a square that is situated away from the street.

This square, with partially sunken interior courtyards around the gallery house, accommodates the public life between the buildings. A basalt base, into which benches are integrated here and there, interlocks the buildings with each other.

* photo – left: *Looking from the gallery’s portico towards the atelier-house and the street; right: The gallery

* photo – left: *Looking from the gallery’s portico towards the atelier-house and the street; right: The gallery

It forms part of the gallery and studio houses, as well as the portico and outside staircase of the old building, and also reaches the ground floor of the adjoining northwestern terrace-end house. In this way, the chthonic material interlocks the buildings with the nearby environment of the city.

The studio building near the street continues a series of residential buildings at a joint between closed and open development, while the gallery building is situated in a more recessed position on the slope, pointing the way towards the centre of the ensemble. Symbolically marked by the cantilever arm of the freight elevator, it accommodates the art location in its exhibition wing on two floors. By contrast, the studio building is orientated towards the street and has more private purposes. It is thereby placed in front of the inner square, acting as a kind of filter towards the street space.

*Section through the atelier-house

*Section through the atelier-house

Like the neighbouring Haus Hundertacht, the choice of materials has a symbolic level that above all performs an urban development task: Inside the gallery building, fine wooden and stone flooring ennobles the exhibits, but its actual power is drawn from the exterior space, where the base binds the buildings together and interweaves them with their surroundings.

Info & credits

Place: Bonn

Project and construction: 2009–2015

Collaborators:Christof Berkenhoff, Matteo Casola, Stefan Dahlmann, Matthias Hiby, Till Robin Kurz, Christoph Lajendäcker, Paolo Marra, Olga Rausch, Kerstin Rothmann, Luca Sirdone, Christa Wigger