The restoration history of the building with few apartments at 1, Sf. Ștefan square, Bucharest, and the remodelling and lay-out of its attic is, in itself, anything but spectacular. Its results are those of a normal course of things, of moderate-budget, not overly complicated, works, which should be done periodically on any building. Yet the frequency with which we encounter, in Bucharest, a coherent restoration of a Modernist building belonging to several owners – therefore, without the support of city halls, and entailing the initiative and responsible cooperation of a group of inhabitants – makes such an accomplishment fall under the extra-ordinary, it gathers over 500 likes a day1 and the admiration of those who know what this adventure, full of bureaucratic and inter-human obstacles, requires.

Text: Ilinca Păun Constantinescu

Photo: Tudor Constantinescu

The Art Deco heritage of Bucharest is quite widespread and rich in typology (public buildings, offices, hotels and residential buildings of varying densities and heights), and it takes extremely varied and playful stylistic shapes. This is because, as Mihaela Criticos2 puts it, this form of gentle Modernism, at the same time eager for progress and tolerant to tradition, was perhaps the most appropriate for Bucharest in the interwar period. Today’s precarious state of this heritage and the small successive individual changes, such as balcony enclosures, roof framing changes, burying the delicate facade ornaments under polystyrene, sometimes render the initial compositions unrecognizable. Of course, degradation in the sense of not having had any renovation since they were built is still an opportunity to see parts of the original finishing and details. But this also falls under the sign of precariousness. In this respect, the newly-launched plastering recipe book of inter-war Bucharest, produced by the Pro Patrimonio foundation3, comes at the right time for the future restorations, and partially replaces a necessary institutional endeavour.

The apartment building in Sf. Ștefan Square is a representative of residential typology, a “Modernist little block of flats”, which articulates the fronts of the Popa Soare St. and of the Sf. Ștefan Square in the Jewish Quarter. Set in a minor, yet deep and rather well preserved fabric, from an urbanistic standpoint, the block rests in a small respite provided by the widening of the intersection and by the Sf. Ștefan park, and plays well on its role of end-of-perspective as seen from Popa Soare, through the soft monumentality of its symmetrical facade, with its vertical and horizontal play of lines, characteristic of a crystallized Art Deco (as we were to later find out from a brick unveiled during the works, bearing the alleged year of the initial construction site, 1932). A seductive image, which could only captivate us as well, in the autumn of 2013, when we were contacted by the owner of the block’s attic, Damiana Oțoiu, to remodel this space which functioned as storage, except for some rooms used by the house servants in the past. I remember the disjunction in the building’s logic, which I felt when I first climbed to the last floor. The modern facade and the high gables hide a very traditional roof-structure. Inside, you felt in a completely different world, no longer modern.

*The building before rehabilitation

*The building before rehabilitation

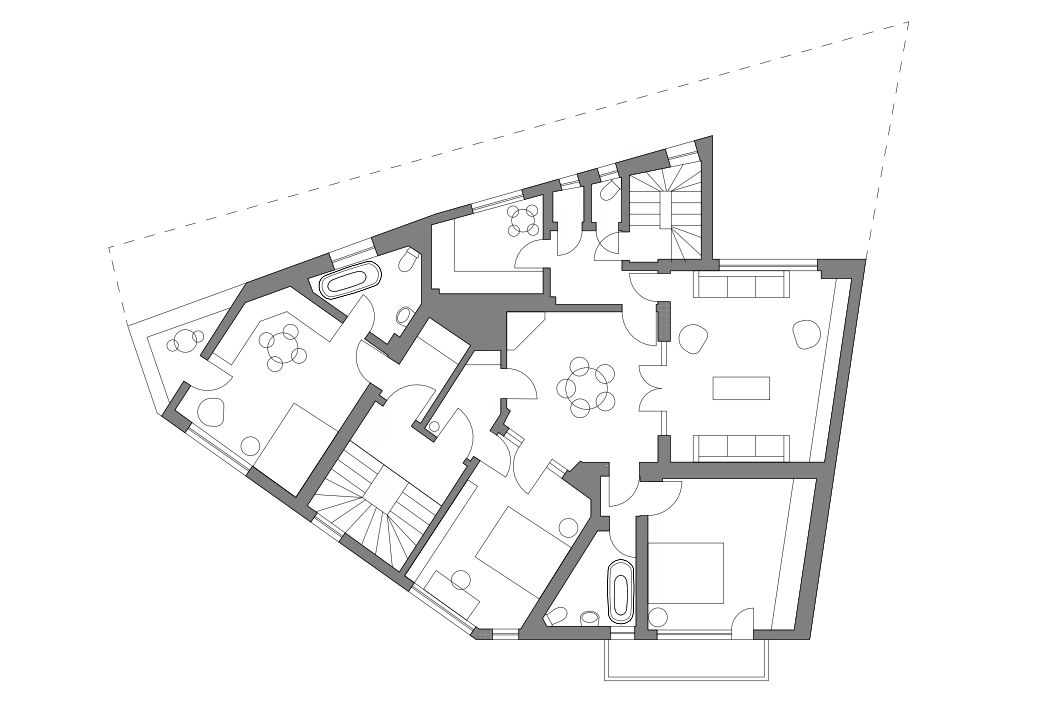

It needs to be said that there is a certain fluidity to the spaces of current floors, yet we cannot speak of a spatial Modernist continuum – as the rooms remain well-delimited, distributed through French windows from a central hallway. And the block, as it happens with most buildings of this type, has very a very clear division between the representative front and the circulation in the back that connects all service spaces, including the attic. In fact, the project’s odyssey started with the spatial re-thinking of the attic, and with the proposal to centre the approx. 130 sqm space around a huge library-wall, which would separate the kitchen from the living room. Visual communication between between the spaces is achieved by inserting in the library the windows salvaged from a construction site of our office, then under way at 40, Rodiei St. (1919 social housing).

*The attic before rehabilitation

*The attic before rehabilitation

Damiana Oțoiu owns a few thousand books, she loves Bucharest history and permanently collects antiques from the far corners of the world, which she frequently travels as part of her anthropology research – so it was only natural that she was happy and quick to receive our proposal.

*The attic. The refurbishment is in full process

*The attic. The refurbishment is in full process

This project option entailed the remodelling of the roof (with small alterations to the framing), the replacement of the wooden structure, which was under-sized an in a poor state, and repositioning it over the walls of the floors below, for reasons of structural continuity. All these required a structural survey of the entire building. At that turning point, our client seized the occasion to use her individual project to trigger some works on the whole construction, and proceeded to convince all the owners that it was the right moment for an outside building site. From that point forward, the project gained another focus for us. Beyond punctual consolidation interventions, the facade restoration project itself required something common sense, theoretically easy to repeat by anyone. But in practice, the beauty of such a building rests with such delicate architectural features, that it can sometimes be overlooked or brutally altered. Therefore, the first step was to clean up the harmful elements of the facade (fortunately, not many), then to identify the valuable elements of architectural language.

*The building after rehabilitation

*The building after rehabilitation

Then came the restoration and the enhancement of the facade elements: the hardware accessories (the staircase stained glass joinery, railings), or the tin ones (rectangular downpipes, tin screens on jambs or flanges), preserving all the grooves, striations, parapet clippings, horizontal and vertical bands and, especially, restoring the stone plaster, observing the rugged and the smooth areas.

*The building after rehabilitation. Details

If we were to draw a line at the end of the exterior building works, this correct result, which should be ‘natural’, comes after a much too difficult journey. Of the six years of work, over four were taken by the approvals and the rehabilitation, while the attic is still under construction. In terms of time, the design took and consumed much less than the entire bureaucratic part, of running to and fro between points A, B, and Z, managing the agreements from all the owners, the cost of the works, convincing third parties. We got ourselves involved in all those things, alongside Damiana Oțoiu, more than it falls under the attributions of an architecture office – from driving neighbors to the notary’s office, to periodical journeys throughout the city, to put pressure on the issuing of approvals, to searching the appropriate team of workers and the desperation of the periodical flee of workers, plus the site-related wildcards.

This may seem a Sisyphean road. If it is not, it is first and foremost due to the owners really wanting to restore the building and to call on professionals to do it. Although it had only started from the thought of arranging her own space, our client understood that it was an unrepeatable moment, and she directed her finances and energies to the altruistic gesture of restoring the beauty of a facade. Therefore, the restoration history of the building with few apartments at 1, Sf. Ștefan Square, is first and foremost about tenacity: that of the owners, of the constructor, and of the architects.

Notes:

1 In Bucharest. Modernism Art Deco 1920-1945. Un Ghid vizual de arhitectură, Asociația Igloo Habitat&Arhitectură, 2018 and Mihaela Criticos, Art Deco sau modernismul bine temperat., Simetria, Bucharest 2010

2 Post by Rezistența Urbană / București 2.0, Cartierul Evreiesc https://www.facebook.com/rezistenta/posts/2452147551526161

3 Ruxandra Sacaliș, Texturi uitate: Bucureștiul interbelic, Rețetar de tencuieli, Pro Patrimonio, Bucharest 2019

Info & credits

Project initiated by Damiana Oțoiu, co-owner

Co-owners and contributors: Andreea și Călin Goia, Silvana Oțoiu

Construction, construction survey: Doru Giuglea

Construction year and architect: 1932, Sady Herivan (unconfirmed, ongoing research)

Restauration, remodeling: Ilinca Păun Constantinescu, Tudor Constantinescu, Ideogram Studio