At least three of the words I used in the title raise questions beyond the aesthetic register. First, ‘guild’. The idea of belonging to a ‘professional group with common interests’ (a possible definition of the guild) contains a cultural anachronism, as the directions in which architecture is practised today are defined precisely by specific interests. Then, the juxtaposition of the words ‘woman architect’ or ‘women in architecture’ should be used only as a possible footnote to the hypothetically resolved issue of embracing diversity of all professional figures. Without the intention of dividing or simplifying recent history and maintaining these caveats, the words will still need to be used.

Text: Ilinca Pop

We know that the ‘woman architect’ should be rather spoken of in neutral terms – simply ‘architect’ – not in an attempt to elude the systemic problem of gender discrimination, but because, in an ideal situation, this issue would have already been overcome. We are still starting to begin building different perspectives, especially if we refer to the macro level of the discussion (concerning the whole society, not just the profession) – we depart from the reality that we are only 84 years away from the moment when women were allowed to vote in Romania. It is true that, as far as the field of architecture is concerned, problems such as the pay gap seem to be less acute than outside the country, and career advancement in any specialisation of architecture seems to be less determined by gender. There is still a real need to affirm the values that ‘difference’ produces, although it is true that the categorical view (women vs. men) should perhaps be removed from the toolkit, especially in the context of gender inclusivity.

If our problems seem to be less acute it is useful to have an overview of recent history, which could explain the recurrence of the ‘woman architect’ in the Romanian professional landscape. From the mid-1920s, when the first women were accepted at the Higher School of Architecture, until today, a century later, the communist period has occupied a significant time – this is also the time when a kind of collective professional identity took shape – although it is to be determined to what extent and in what forms it still exists today.

*An icon of post-war Romanian modernism: The Predeal Train Station (architects: Irina Rosetti, Ilie Dumitrescu, engineers: Mircea Mihailescu, Ildikó Bucur Horváth) / Photo: Marius Vasile

*An icon of post-war Romanian modernism: The Predeal Train Station (architects: Irina Rosetti, Ilie Dumitrescu, engineers: Mircea Mihailescu, Ildikó Bucur Horváth) / Photo: Marius Vasile

A snapshot of the region

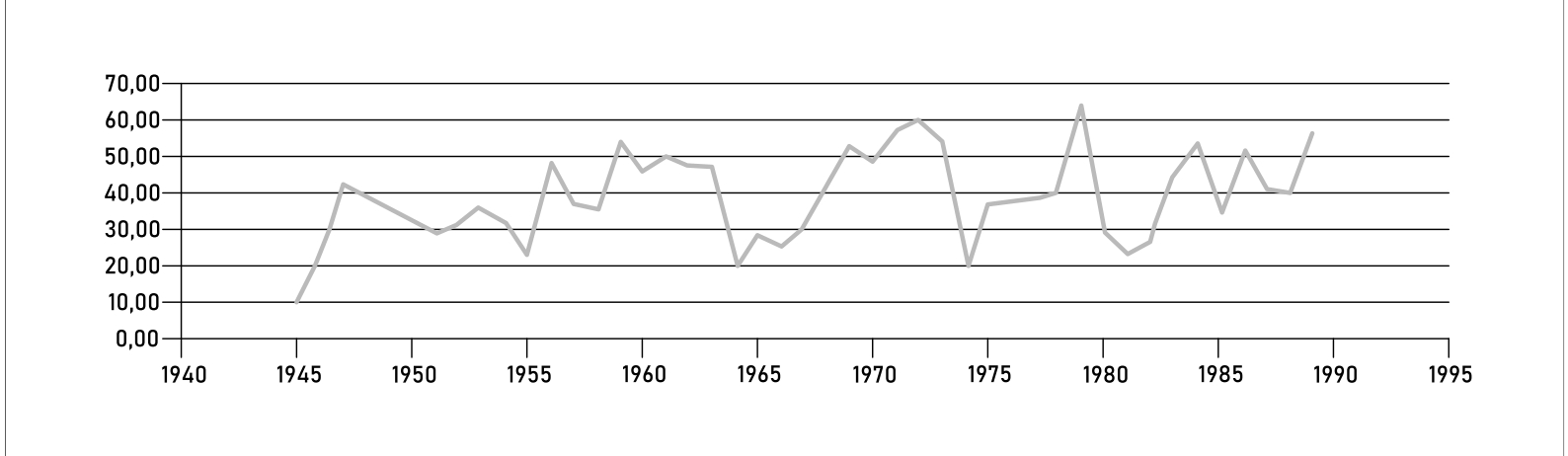

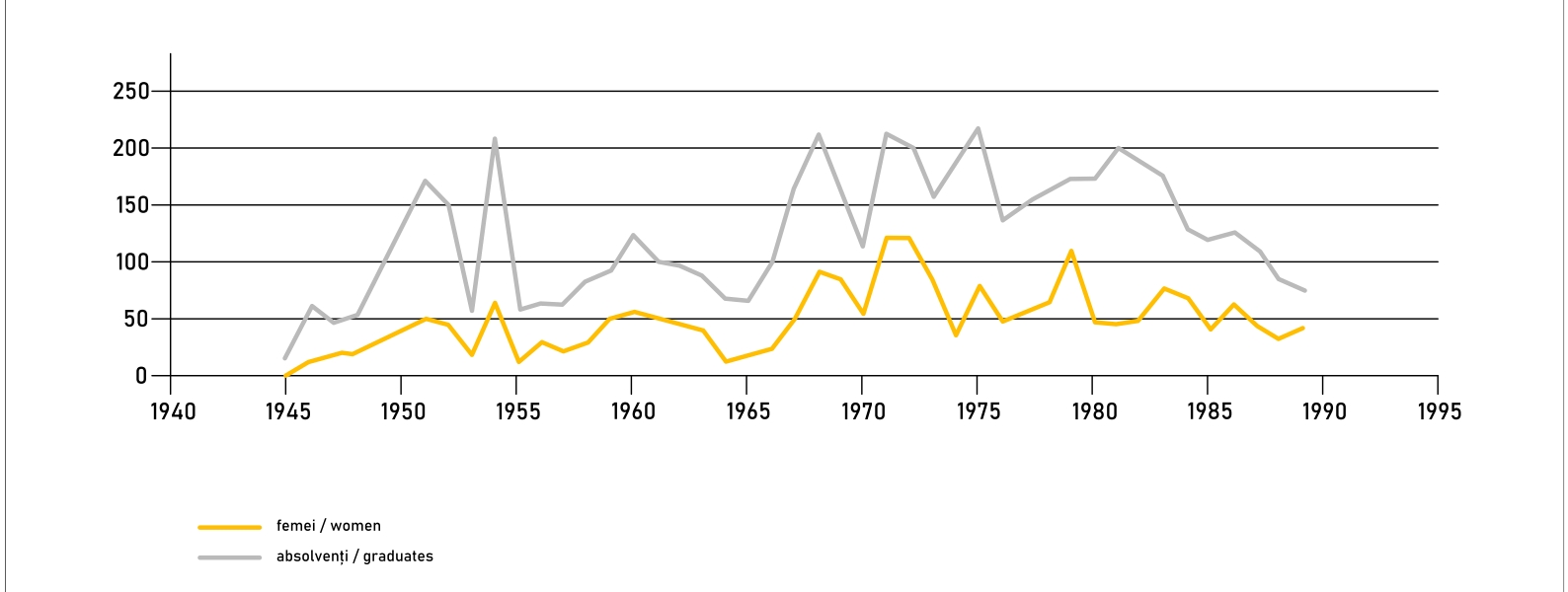

Since the abolition of independent practice in 1952, graduates of the architecture school – operating under the name “Institute of Architecture” since 1948 – have been working in the collectives of the country’s Design Institutes, often in a situation of imposed professional anonymity. Of these graduates, around 1950, about 30% were women – a significant percentage when one considers that in 1925 Henriette Delavrancea-Gibory was among the first graduates of the School.

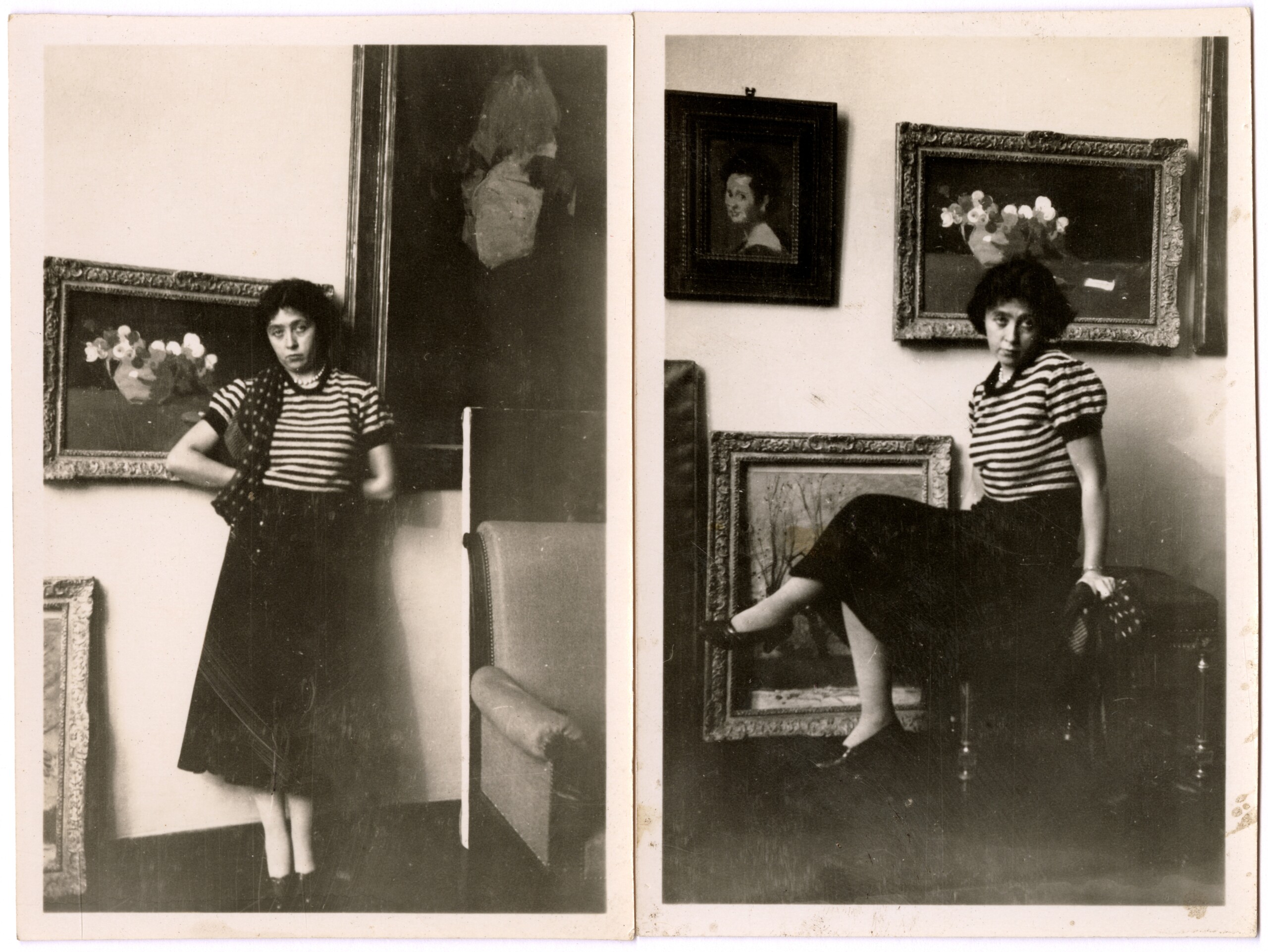

*Henriette Delavrancea in the 1920s

*Henriette Delavrancea in the 1920s

The year in which the Institute of Architecture was separated from the Polytechnic (1948) as an independent higher education establishment was also the year in which women were given the right to vote in Romania. During the years of the communist regime, however, the practice of most male and female architects remains under-researched and under-recognised, and the archives of some of the institutes, recently brought back to public attention1, are in a state of mess that is symptomatic of the lack of affective exercise towards the design work of those years.

The (ideological) assumption of equality introduced by totalitarian (socialist) regimes in Eastern European countries means that the situation of women here differs from that in the rest of the continent. Whether or not the Western feminist movement (historically recorded as the ‘second feminist wave’) around the 1960s has regional echoes, and if so, what nuances does this ideologically mediated cultural transfer of socialism introduce? is a question that goes beyond the limits of the brief overview we propose. Returning, however, to the practice of architecture, the sphere of politics dictates the dominant way in which professional practice operates after the years of the establishment of totalitarian regimes – by the public commission. But even if this reality would seem to condemn many (and especially women) to professional dissatisfaction, Ana-Maria Zahariade reminds us that there are female architects who are recognised for their work and who manage to build important careers in these years, among whom she mentions Sofia Ungureanu, Paraschiva Iubu, Alexandra Florian, Anca Borgovan or Ioana Grigorescu.

It is true that in Romania women don’t generally occupy leading roles in Design Institutes, but if we look at the region of Eastern Europe, in the former Yugoslavia, at only 29 years old, Svetlana Kana Radević was awarded the Federal Borba Prize (1967) – the kind of individual recognition that architects like Jane Drew or Denise Scott Brown have long lacked, who were practising at the same time in Western countries (and moreover alongside architects such as Le Corbusier and Robert Venturi, which did not help their professional advancement, but rather the opposite). In Romania, a possible ‘pendant’ to this example (although the differences in vision between the former Yugoslav regime and the Romanian one are notable to say the least) could be considered Anca Petrescu’s career, but only in terms of the kind of institutional trust and recognition (of ‘Authority’) to which women have access in the context of totalitarian regimes in Eastern Europe.

An exception is also the career development of Henrietta Delavrancea-Gibory, who, although not necessarily in a privileged position directly in relation to the ‘regime’, consolidates her professional figure. In the mid-1950s, the architect coordinated the design of several hospitals or medical pavilions in Bucharest, including the Fundeni Clinical Hospital between 1949 and 1959 and the Oncological Institute Filantropia between 1950 and 1960. However, even in Henriette’s case it is useful to take a moderate view, as it is well known that the architect’s interest turned towards the study of traditional architecture around the 1970s, and her professional discourse later took on a very critical dimension towards architects who strayed from the “national spirit”.

*Percentage of women within the total number of graduates, 1945–89 (redrafted after Ana Maria Zahariade, „The drawing board au féminin: Women architects in Communist Romania” in Mary Pepchinski and Mariann Simon (editori), Ideological Equals, Women architects in socialist Europe 1945–1989, Londra & New York: Routledge, 2017, p. 80

*Percentage of women within the total number of graduates, 1945–89 (redrafted after Ana Maria Zahariade, „The drawing board au féminin: Women architects in Communist Romania” in Mary Pepchinski and Mariann Simon (editori), Ideological Equals, Women architects in socialist Europe 1945–1989, Londra & New York: Routledge, 2017, p. 80

*Number of women among the total number of graduates, 1945–89 (redrafted after Ana Maria Zahariade, „The drawing board au féminin: Women architects in Communist Romania” in Mary Pepchinski and Mariann Simon (editori), Ideological Equals, Women architects in socialist Europe 1945–1989, Londra & New York: Routledge, 2017, p. 81)

*Number of women among the total number of graduates, 1945–89 (redrafted after Ana Maria Zahariade, „The drawing board au féminin: Women architects in Communist Romania” in Mary Pepchinski and Mariann Simon (editori), Ideological Equals, Women architects in socialist Europe 1945–1989, Londra & New York: Routledge, 2017, p. 81)

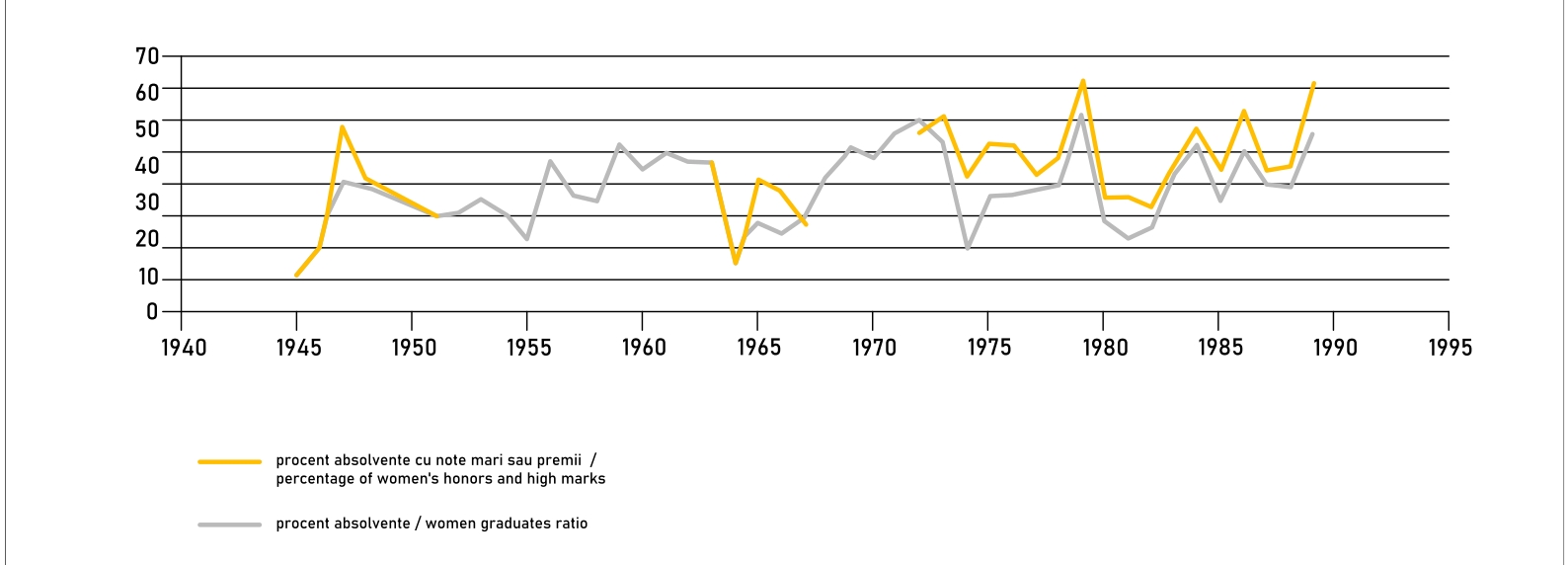

*Percentage of women among the total number of honors and high marks recipients, 1945–89 (redrafted after Ana Maria Zahariade, „The drawing board au féminin: Women architects in Communist Romania” in Mary Pepchinski and Mariann Simon (editori), Ideological Equals, Women architects in socialist Europe 1945–1989, Londra & New York: Routledge, 2017, p. 81)

*Percentage of women among the total number of honors and high marks recipients, 1945–89 (redrafted after Ana Maria Zahariade, „The drawing board au féminin: Women architects in Communist Romania” in Mary Pepchinski and Mariann Simon (editori), Ideological Equals, Women architects in socialist Europe 1945–1989, Londra & New York: Routledge, 2017, p. 81)

Cultivating collective resistance

The ‘kinder’ realities that the profession in Romania would seem to experience in terms of gender dynamics are valuable not only in relation to the notoriety of some authors or ‘author’ projects, which, despite the exceptions listed, appear rather as isolated events during the communist regime. The most important thing, in this period, is in fact that difference becomes a resource for enriching collective resistance against the multiple constraints of the political regime. The ‘guild’ prepares its future members from the early years of their studies for this collective state of ‘exception’. Ana-Maria Zahariade speaks of a ‘heterotopia’ of the School of Architecture, “a place where gender equality was rampant and women enjoyed the perfect conditions to bloom into architects […] Despite the ideological restrictions that prevailed with varying intensity throughout this period, architecture school was a phase of unusual freedom (certainly relative), a parallel world of professional and social adventure. […] This was a protected realm. Throughout this period, the professors kept the heterotopy alive. Unofficially they upheld a code of behaviour, which reinforced their identity as members of the guild […] thus creating a (moderately) free and elitist atmosphere, which was admired and envied by all students in Romania.”

The School’s atmosphere and values are also reflected in the statistics on the recognition that female student architects receive during this period, with no noticeable gaps that can be attributed to gender differences. However, the fact that the violence of the regime led to the consolidation of an egalitarian spirit within the ‘guild’ in no way diminishes the harsh realities of the period. An important lesson here, however, is that of working ‘together’, of openness to difference and that of the profession’s democratisation. The same profession must remember and collectively defend its shared values at all times – even in the absence of (outside) pressure that would exceed private interests – from within the School, to the diverse hypostases in which we might find ‘Authority’ today.

*1st photo (top): An informal moment in the Institute for Systematization, Housing and Community Management (ISLGC), 1983, Bucharest / Source: Courtesy of Jeni Luchian-Constantinescu / from Ana Maria Zahariade, „The drawing board au féminin: Women architects in Communist Romania” in Mary Pepchinski and Mariann Simon (editori), Ideological Equals, Women architects in socialist Europe 1945–1989, Londra & New York: Routledge, 2017, p. 88

Reading list:

BROWN, Denise Scott Brown. „Room at the Top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture”, in Ellen Perry Berkeley (ed.) Architecture: A Place for Women, New York: Smithsonian Books, 1989.

KATS, Anna. „Svetlana Kana Radević (1937-2000)”, in Architectural Review, Masculinities + W Awards, March 2020.

PEPCHINSKI, Mary and Mariann Simon (eds.), Ideological Equals, Women architects in socialist Europe 1945–1989, London & New York: Routledge, 2017

ZAHARIADE, Ana Maria. [Ro] „Arhitectura la feminin. Femei arhitect în românia comunistă”, Revista Arhitectura, Femei în arhitectura românească, no. 2-3 (2017)