Text: Mihai Duțescu

Foto: Andrei Mărgulescu, Mihai Duțescu

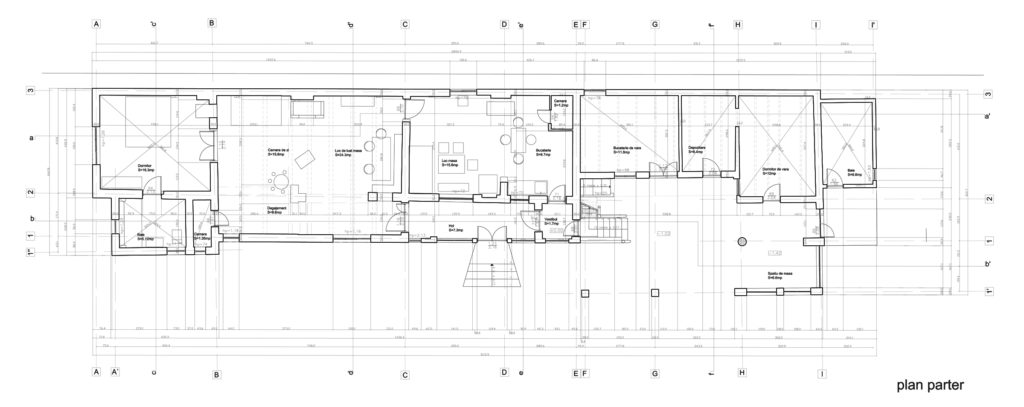

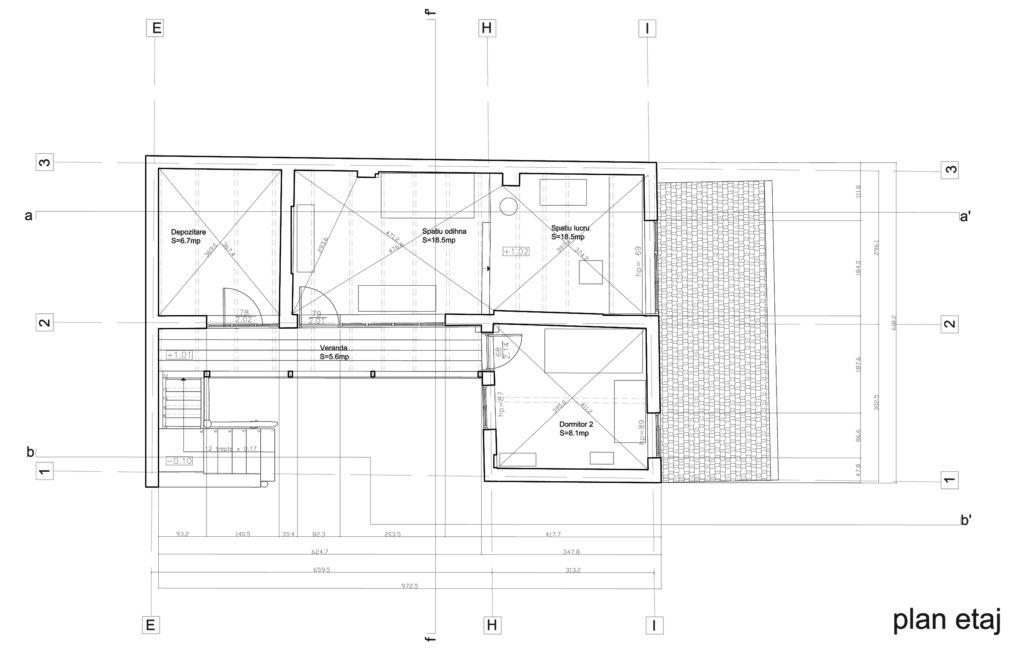

Plans: survey by the students of the atelier of Prof. Mircea Ochinciuc, 3rd year, Ion Mincu University, Bucharest, 2009-2010; assistants: Melania Dulămea, Mihia Duțescu, Adrian Moleavin

Although I don’t particularly resonate with his Surrealist poetry, I have always liked Gellu Naum, even before it was cool to like Gellu Naum. I would take my students on field trips to his Comana house, to do projects there, back when it wasn’t yet fashionable to visit Comana, any more than it was to visit any other village bordered by forest, thirty kilometers outside Bucharest, and when the house was virtually unknown.

The house is located on Gellu Naum Street in Comana, today a rather large and proud commune in Giurgiu County. Naum bought it in the 1960s, if I’m not mistaken, and set to improve it, working together with his wife Lygia who, again I hope I’m not mistaken, had some experience as an interior designer. And together they transformed an ordinary southern Romanian house into an ideal place, at least for me, that is: a combination of vernacular architecture and consciously made cultured interventions.

*Plans: section bb, ground floor, 1st floor

*Plans: section bb, ground floor, 1st floor

The site is dominated by the garden, the house itself being overgrown with plants—Virginia creeper, ivy, honeysuckle, and other creepers and climbers. The vegetable patch now gone, the garden is overrun with flowers, some as tall as a person, and perfectly anonymous in their beauty. There might very well be some roses and lilies and other recognizable flowers in there, but even a city boy who grew up in the countryside like myself couldn’t name most of them. The garden and the blurry outline of the house make you instantly think of a Horia Bernea painting.

To give you a better picture, the topography of the place is very important as the back of the yard is a good six meters lower than the front. And there, at the back, you will find, lo and behold, the “swamp,” one of Naum’s recurring archetypes. This is in fact a stretch of the Neajlov Delta, where the poet would go fishing, rowing straight out of his own backyard. In addition to the “swamp,” other “anchors in reality” from his poems—the wet socks, the patience dock, the boat, the manure pit, etc.—are, I assure you, as real as they get.

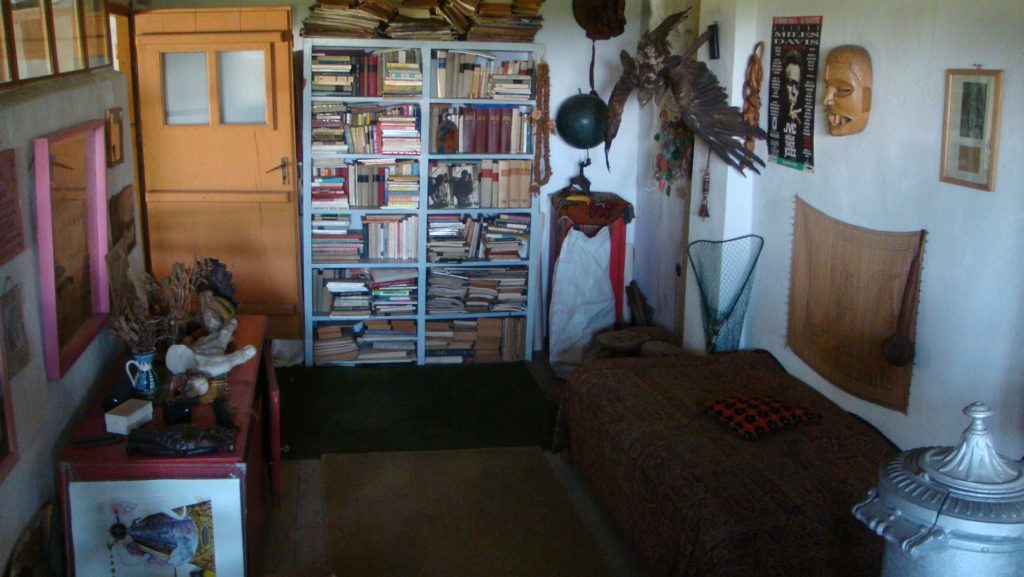

Scattered all over the yard, you can see the signs of Gellu Naum the artist, inhabiting this space. There is, for instance, the cat’s head carved in the wooden baluster by the entrance—Japonica, the poet’s cat, might have modeled for it—or the carved human head that decorates one end of a bench put together from two tree stumps and a basic wood plank, imbuing these most mundane objects with something otherworldly. Or the fact that the same bench sits across the yard, against the grain, as it were, in relation to all the other physical landmarks.

I believe this to be the one unifying feature of the house and the place: the low-key but persistent warping of the everyday—another word for reality as reflected in the construction elements, household items, etc.—by way of small artistic gestures. Whether we like them or not, whether they have artistic or merely sentimental value, some of these gestures are clearly meant as Surrealist statements, while others could be simply echoing such statements like the various ethnic artifacts brought back by the couple from their trips abroad or the gifts received from the odd Western poet or journalist who might have ventured to Comana to visit one of the last European surrealists.

Compared to the plain style of the original house, the most visible and, in my opinion, the most successful intervention is the back of the house, i.e. the former outbuilding attached to the house. The shed was converted into a guest room and a studio for the poet—with an astounding panoramic view of the “swamp”—to which a storeroom was added. Access to all these rooms is from a wooden passageway, while a wooden external staircase provides access to the passageway.

Additionally, along the entire length of the outbuilding, a big canopy projects outward, supported by wooden and concrete posts, which are slightly out of scale, but therefore even more authentic. This outdoor space is enclosed to the north and the east to form a geamlâc (a glazed porch with wood, or, like here, steel lattice typical of Balkan architecture), and in this alcove are nestled a peasant wooden table and chairs.

The interior and some of the exterior interventions are low-key in the most positive way. Once again, the small artistic gestures and insertions are at work, infiltrating the conventional household setting, slightly warping reality, and reminding you, once the initial bafflement wears off, that you are in a cultural space created by one of Romania’s greatest contemporary poets.