We are in one of the former semi-rural areas in northern Bucharest, where most all old houses have made way for post-Socialist villas (especially since the 1990s). The new constructions, with a few exceptions, do not possess any architectural value. But they generally observe the model of the house with a yard, it’s true, a house with two levels, sometimes with an extra attic. The neighbourhood uglier, is more crammed and more chaotic than it used to be but, as there aren’t so many apartment buildings, there still is plenty of greenery, and the general scale remains decent and pleasant.

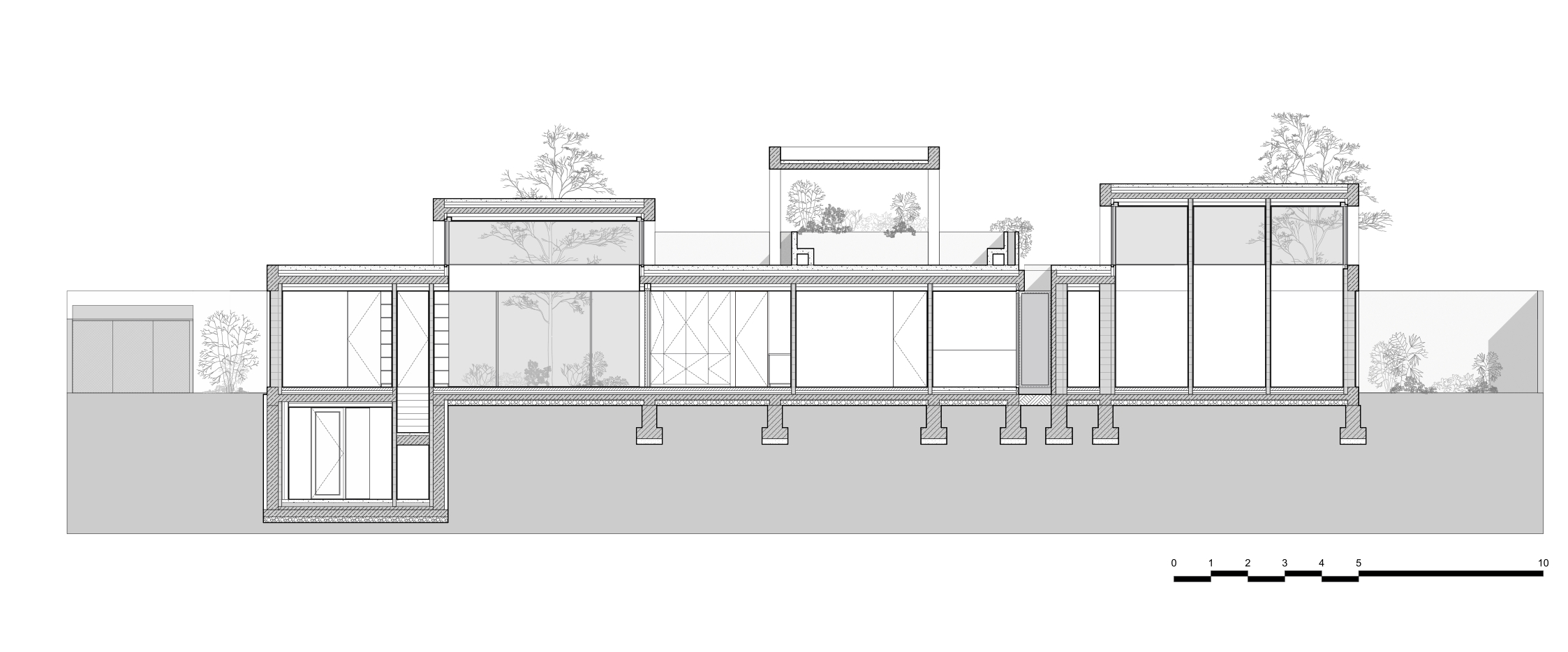

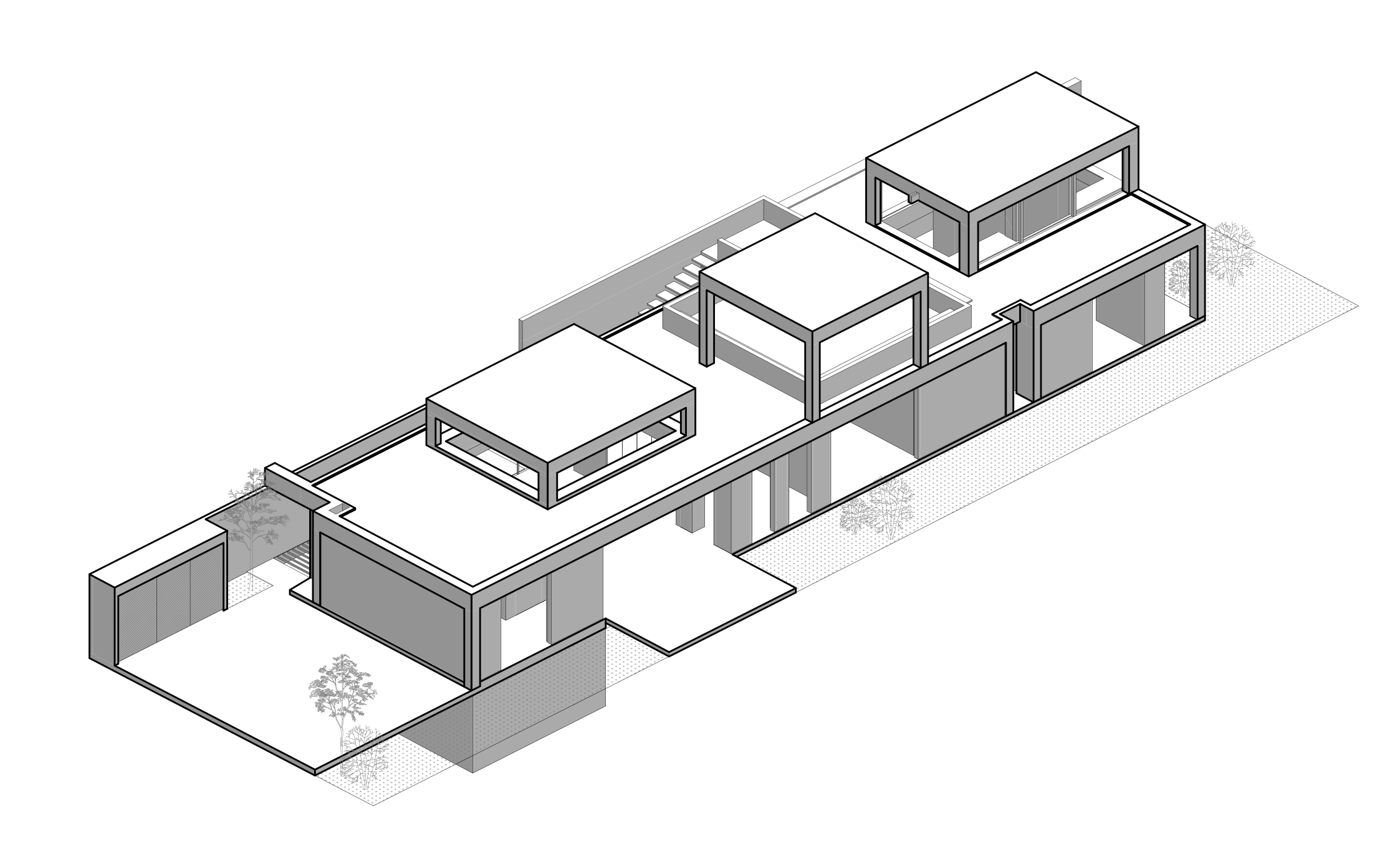

If you hurry by, you won’t even notice that the plot at 6, Dărmănești St. has received a permanent construction. Recessed from the street, with only one level and a sort of transparent gazebos on top, with exposed concrete facades and grey plastering, the house, built for a family of two parents and two children, is barely rises over the semi-transparent fence. But even this minimal presence expresses the project’s two fundamental qualities: on the one hand, the construction’s spread over the entire plot and the merging between inside and outside, and on the other, the architectural expression’s integrity: not only does the structure do its job architecture-wise, it also becomes architecture.

Text: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Photo: Vlad Pătru

Living on the ground

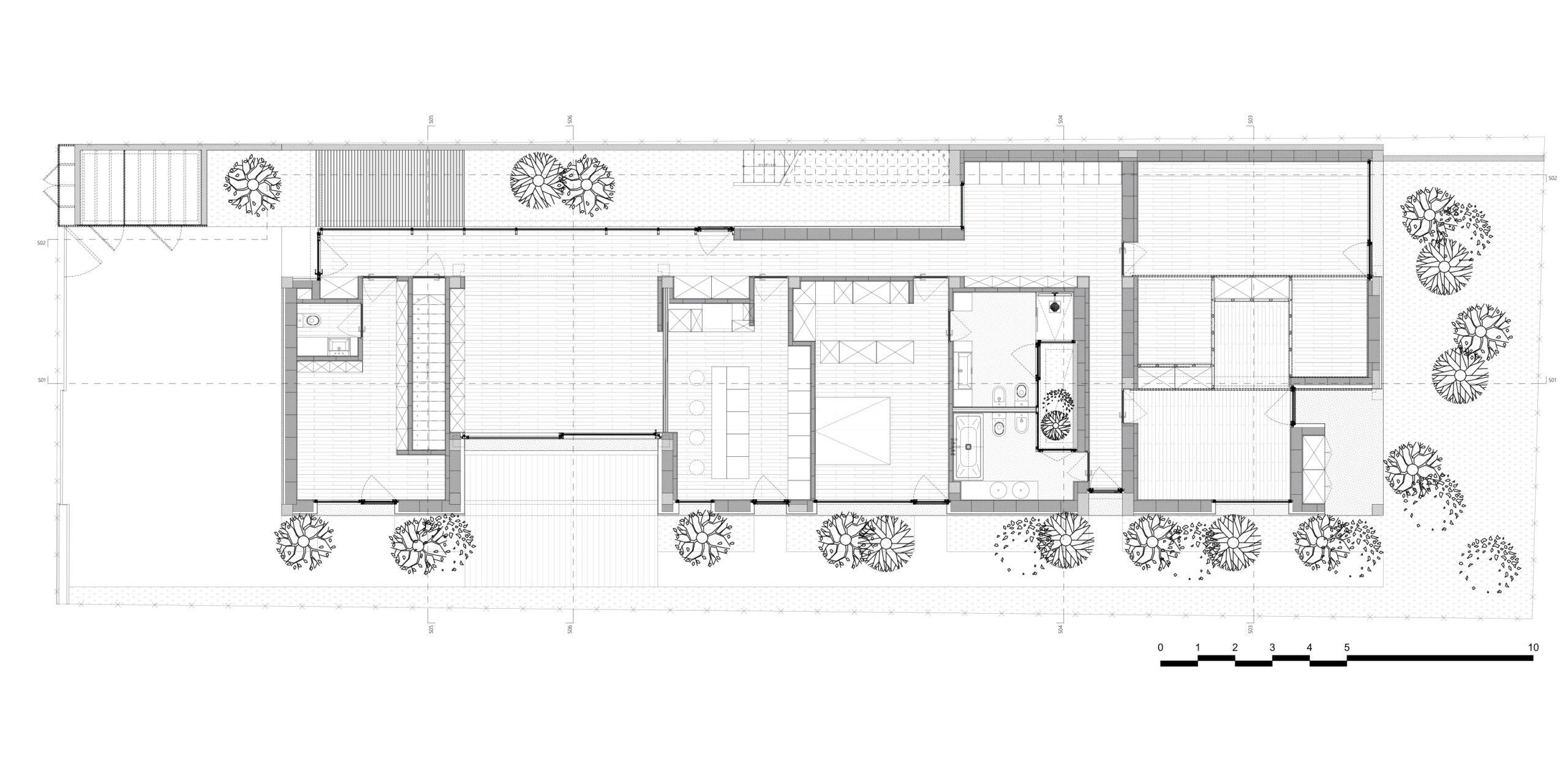

At the start of the project, several variants were studied, including the conventional one of a two-storey house. But the clients were brave enough to accept the idea of living on ground level. This is quite a quite specific model for Bucharest model (in fact, for Romanian lands outside the Carpathians). The plot division and the 19th and 20th century densification in the (semi)rural areas have created narrow, deep plots, in need of lateral recess on at least one side. The result: alternating empty and built strips of equivalent widths. As long as the buildings remain on one level, these courtyards actually receive some sunlight, and the living spaces are in direct contact with them. This is the case here: it is not so much about a house in a courtyard, but rather about a lived-in courtyard, a system of interior and exterior spaces.

The house’s relationship with the outside is a remarkably diverse one for the scale of the project. To the south, the long side opens through large windows and partial recesses.

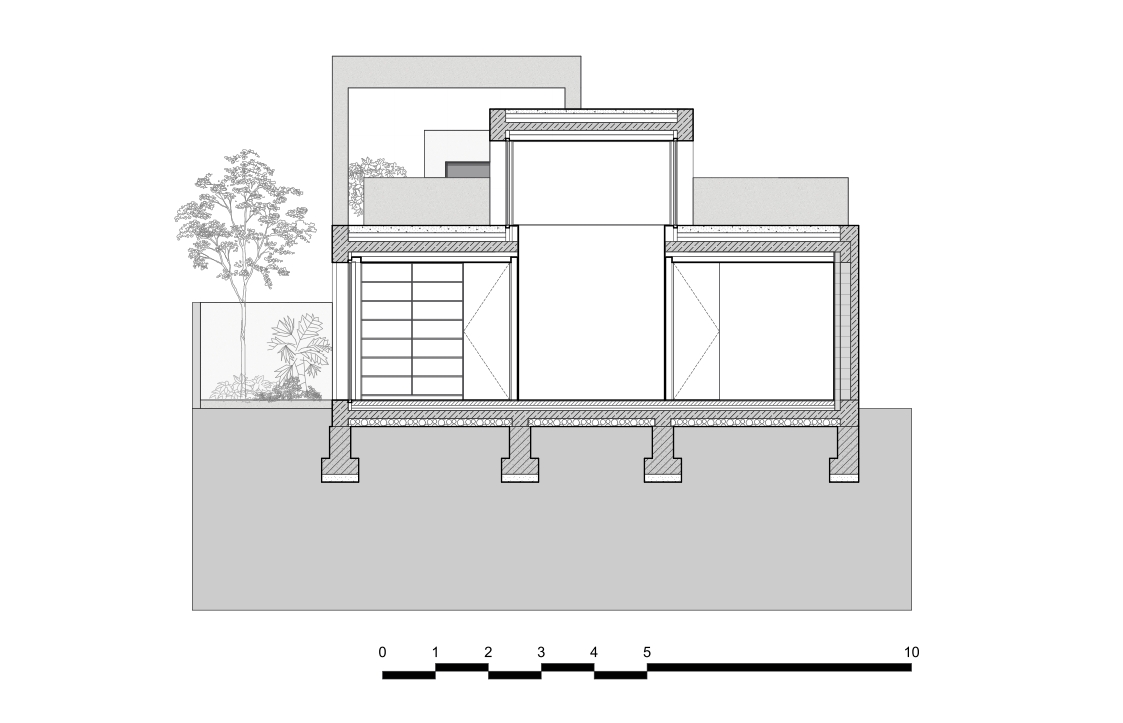

To the north, an agreement with the neighbours has allowed the building of a tall fence, which at some point becomes a house: a series of narrow spaces between two walls is thus born.

A sort of interior street extends towards the fence, a gallery with an entrance at some point, providing access, along the way, to the various rooms, melting down in the living room and then turning around the corner to reach other rooms and then the secondary exit towards the south side courtyard.

The rear side now hosts the children’s two rooms and two generous dressings. If needed, an apartment for a child-turned-adult can be very easily set up, for them to live here at least for a while, with considerable autonomy. In fact, the house’s first room, now a library/office, can become a guestroom.

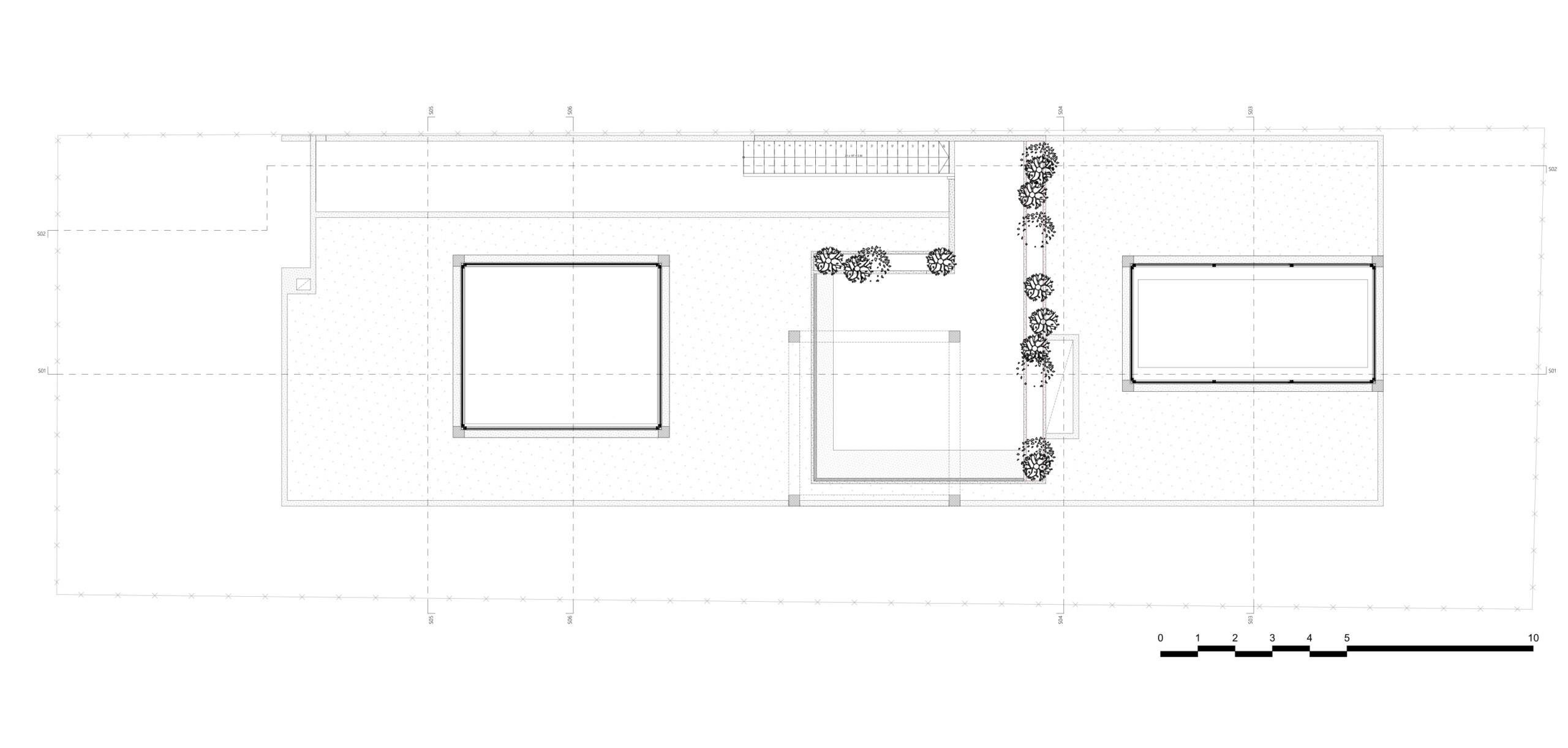

The surface lost in the courtyard is being recovered on top of the house itself. A staircase from the entrance gangway leads to the roof, shaped as a mineral landscape, with some very open areas and some sheltered ones.

In fact, the roof performs and expresses the succession of rooms of different characters, which make up the ground floor. Thus, the day area raises over the rest of the construction, becoming a noble space, a kind of clerestory with light coming from all four corners. The elevation in the children’s area would ease the transformation of this space, that we were mentioning, by the insertion of lofts. The third tall volume is in fact a pavilion set over the terrace – a gazebo, an open-air room protected from sight and from the sun through a perimeter of silver curtains.

Structure produces architecture

The “béton brut” (Le Corbusier), the exposed concrete, as it is currently called, is a material that architects (and people interested in modern art and architecture) really love. It is rough in a good, honest way, it provides mass and and a vibrating surface, it is both artificial and evocative of the natural materials it is made of. It’s true that, when compared to Modernism classical works, exposed concrete has evolved a lot. Nowadays it’s unthinkable to assume buildings without thermal insulation. As such, the concrete usually remains exposed on the inside (meanwhile this has become a nearly banal element of interior design). If you want to achieve it on the outside, the double-wall formula is normally used: a bearing wall, a layer of insulation and then a second exterior wall, which “gives face” without actually bearing anything.

What is seen here outside is truly the structure itself. A system of concrete pillars and slabs is filled with light closing materials – gas-formed concrete masonry and plastering, glazing, curtains. The thermal insulation is moved on the inside, in fact warm sealed boxes are created inside a cold envelope.

The massive exoskeleton contrasts with the neutrality and, at times, the preciousness and delicacy of the closings and of the interior. The light coming in from the courtyards is creeping through gangways or spilling from overhead, contributing to the richness of situations and the joy of living. It is a good house. Inclusive from a practical standpoint, which is not necessarily the case with innovating architecture. One of the small details in this respect: the windows on the top side of the day space are fixed. This minimizes joinery and is cheaper than a remote-opening system. But for this reason one cannot clean them on the outside from the inside, and that is normally a maintenance nightmare. But here you can reach them from the terrace. This is not the only gesture designed for the good functioning of the house. I believe that, in general, it will behave well long after the architect is gone.

*Terrace plan

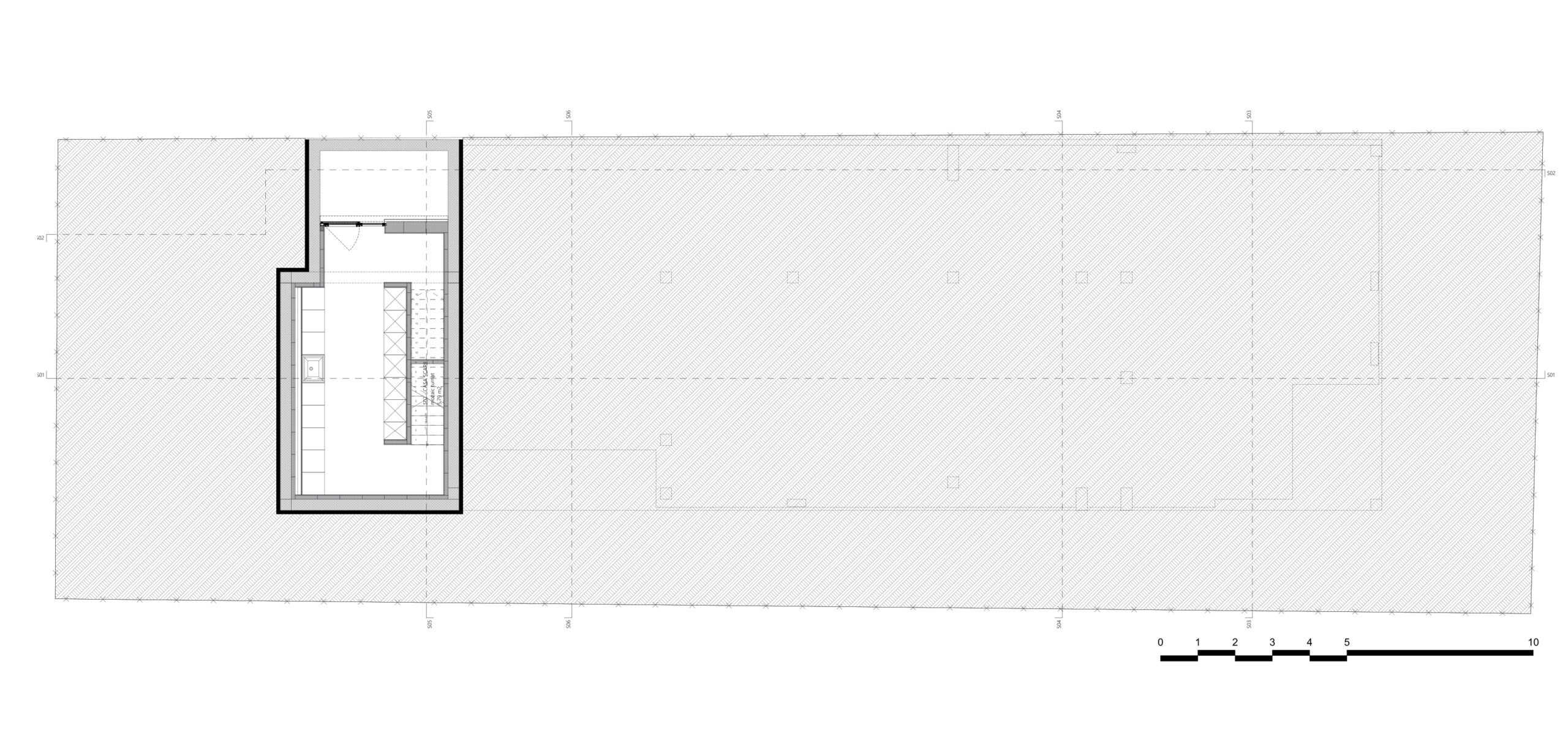

*Terrace plan *Underground plan

*Underground plan

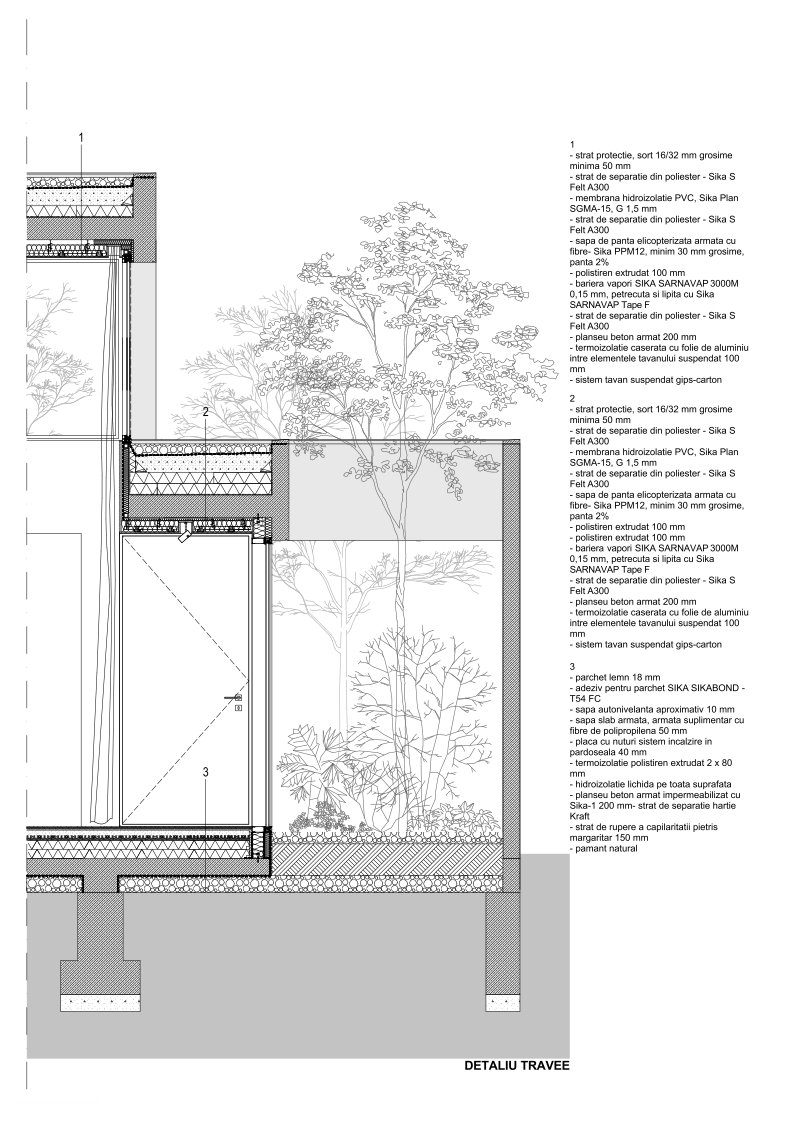

1: – Protection layer, 6/32 mm, minimal thickness 50 mm / – Polyester separation layer /- PVC waterproofing membrane, 1,5 mm / – Polyester separation layer / – fiber-reinforced screed, 30 mm minimal thickness, 2% slope /- Extruded polystyrene, 100 mm / – Vapor barrier, 0,15 mm / – Polyester separation layer / – Concrete slab, 200 mm / – thermal insulation with aluminium foil, places between the suspended ceiling elements, 100mm / – plasterboard suspended ceiling

2: – Protection layer, 6/32 mm, minimal thickness 50 mm / – Polyester separation layer / – PVC waterproofing membrane, 1,5 mm / – Polyester separation layer / – fiber-reinforced screed, 30 mm minimal thickness, 2% slope / – Extruded polystyrene, 100 mm / – Extruded polystyrene, 100 mm / – Vapor barrier, 0,15 mm / – Polyester separation layer / – Concrete slab, 200 mm / – thermal insulation with aluminium foil, places between the suspended ceiling elements, 100mm / – plasterboard suspended ceiling

3: – parquet, 18 mm / – parquet adhesive / – self leveling screed, 10 mm / – screed with polypropylene fibers, / – floor heating system, 40 mm / – Extruded polystyrene, 2 x 80mm / – liquid waterproofing on the whole area / – waterproofed concrete floor / – capillary break, gravel, 150 mm

Info & credits

Adrfess: Str. Dărmănești Nr.6, Sector 1, Bucharest

Design and completion year: 2015 / 2021

Main author: Attila KIM

Design team: Attila Kim, Gabriel CHIȘ Bulkea, Alexandru Szüz Pop, Adina Marin, Andreea Precup

Structural Engineering: 9 Tuplesys- Gheorghe IONICĂ