Participationism is a historiographical construct inspired by mid 1960s’ anthropology and social theories. About twenty years before theorizing, by 1945, Hassan Fathy was testing “participationism” within New Gourna project in Luxor, Egypt. The situation was unique: the Egyptian Department of Antiquities was relocating the local population from the endangered area containing ancient ruins, trying to reintegrate people into sustainable tourism circuit through craft activities that they could undertake. To imagine a new fragment of the village, Fathy relied on timeless images of vernacular architecture made out of earth and adobe, i.e. a technology considered “primitive” by locals who actually wanted a “modern” built environment made of new materials available on the Egyptian market at that time. The architect tried to make people rediscover and reinterpret existing typologies and constructive traditions in a natural way. The “owner-architect-craftsman” triad represented the backbone of its social approach. In terms of space, the space room / cell of the space-structure articulated the entire built tissue.

Moreover, he attempted to answer naturally to some specific cultural and environmental conditions putting the character of the place before the new technologies at hand. He designed a part of the city according to ecological principles based on local typologies such as courtyards with public fountains around which the dense, low housing-carpet is grouped, including rectangular volumes, arches and coverage vaults. Fathy pushed this process to a level that today we consider as “participationist” through a series of improvisations designed to arouse inhabitants’ “numb” sensitivity about history. He made a 1:1 scale model houses so as to demonstrate the civic qualities of his approach.

However, he could not keep residents away from modernity: the houses were irreversibly converted by their inhabitants and the public space was altered by private extensions of foreign material, criticized by architects. It was a double failure: the land as a cheap and environmentally friendly building material was not separated from the poverty image symbolically perceived by the residents, despite Fathy’s architectural performance, while the participationist appearance avant la lettre did not work in a cultural sense. Today’s participationists would have confirmed that residents were right, not the architect who was imposing an idealized image of the past, though honest in relation to the constructive technique and the character of the place.

Both Fathy’s failure and ethical vision resonate over the decades. Any current participationist theory is facing the same set of essential issues related to a moral extent to which an architect can intervene in a community to convert it, the degree of novelty a place can assimilate and particularly, the role of historiographical interpretation in such cases.

* Published in Zeppelin no. 116 / July-August 2013

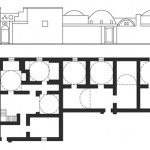

* Illustration: Hassan Fathy – locuinte în Gourna, Egipt, 1946–1952, elevation and plan (redrawn after H. Fathy)

Participationism is a historiographical construct inspired by mid 1960s’ anthropology and social theories. About twenty years before theorizing, by 1945, Hassan Fathy was testing “participationism” within New Gourna project in Luxor, Egypt. The situation was unique: the Egyptian Department of Antiquities was relocating the local population from the endangered area containing ancient ruins, trying to reintegrate people into sustainable tourism circuit through craft activities that they could undertake. To imagine a new fragment of the village, Fathy relied on timeless images of vernacular architecture made out of earth and adobe, i.e. a technology considered “primitive” by locals who actually wanted a “modern” built environment made of new materials available on the Egyptian market at that time. The architect tried to make people rediscover and reinterpret existing typologies and constructive traditions in a natural way. The “owner-architect-craftsman” triad represented the backbone of its social approach. In terms of space, the space room / cell of the space-structure articulated the entire built tissue.

Moreover, he attempted to answer naturally to some specific cultural and environmental conditions putting the character of the place before the new technologies at hand. He designed a part of the city according to ecological principles based on local typologies such as courtyards with public fountains around which the dense, low housing-carpet is grouped, including rectangular volumes, arches and coverage vaults. Fathy pushed this process to a level that today we consider as “participationist” through a series of improvisations designed to arouse inhabitants’ “numb” sensitivity about history. He made a 1:1 scale model houses so as to demonstrate the civic qualities of his approach.

However, he could not keep residents away from modernity: the houses were irreversibly converted by their inhabitants and the public space was altered by private extensions of foreign material, criticized by architects. It was a double failure: the land as a cheap and environmentally friendly building material was not separated from the poverty image symbolically perceived by the residents, despite Fathy’s architectural performance, while the participationist appearance avant la lettre did not work in a cultural sense. Today’s participationists would have confirmed that residents were right, not the architect who was imposing an idealized image of the past, though honest in relation to the constructive technique and the character of the place.

Both Fathy’s failure and ethical vision resonate over the decades. Any current participationist theory is facing the same set of essential issues related to a moral extent to which an architect can intervene in a community to convert it, the degree of novelty a place can assimilate and particularly, the role of historiographical interpretation in such cases.

* Published in Zeppelin no. 116 / July-August 2013

* Illustration: Hassan Fathy – locuinte în Gourna, Egipt, 1946–1952, elevation and plan (redrawn after H. Fathy)