Perhaps the most frequent project title found on mandatory construction site panels in Bucharest is that of “Rehabilitation and expansion”.

Text, photo: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Many of the more valuable projects published lately in Zeppelin also include this expression in their official title. They are not the ones I’d like to address here, but a different type of very, very well-known projects, where ‘rehabilitation and expansion’ translates into ‘demolition and new building’.

Nowadays, especially in protected areas, demolition permits are much more difficult to obtain than back in the ‘90s-2000s. Thus ensued this trick of claiming that you’re not tearing down an old house, but, mind you, you’re transforming it. When the existing building completely disappears during the construction phase, we are clearly dealing with an illegality, as I see it. Of course, we can discuss the gross inefficiency of a system where you can afford to do such things and suffer no consequences, or where you get away with a ridiculous fee.

The major issue is in accepting those situations where not everything, but most everything is demolished, and the administration and society are taking it in stride. More prudent clients or developers have understood that, were they to preserve the facade or a part of it, they can rest easy. Or, you can even get away with it if you completely eliminate the original substance and then rebuild it, carefully or approximately so. Sometimes, as is the case of the oppressive apartment building being built across from one of Bucharest’s most important landmarks, Ion Mincu’s Central School, it’s enough to simply glue on some generic ornaments.

We’ve covered this before. This is serious, because facadism covers the elimination of spaces, of historical substance, of what makes a building valuable. Then, once you allow the demolition of most everything, there is only one step left, such an easy one for a society like the Romanian one, to go all the way.

OK? So, what can be done?

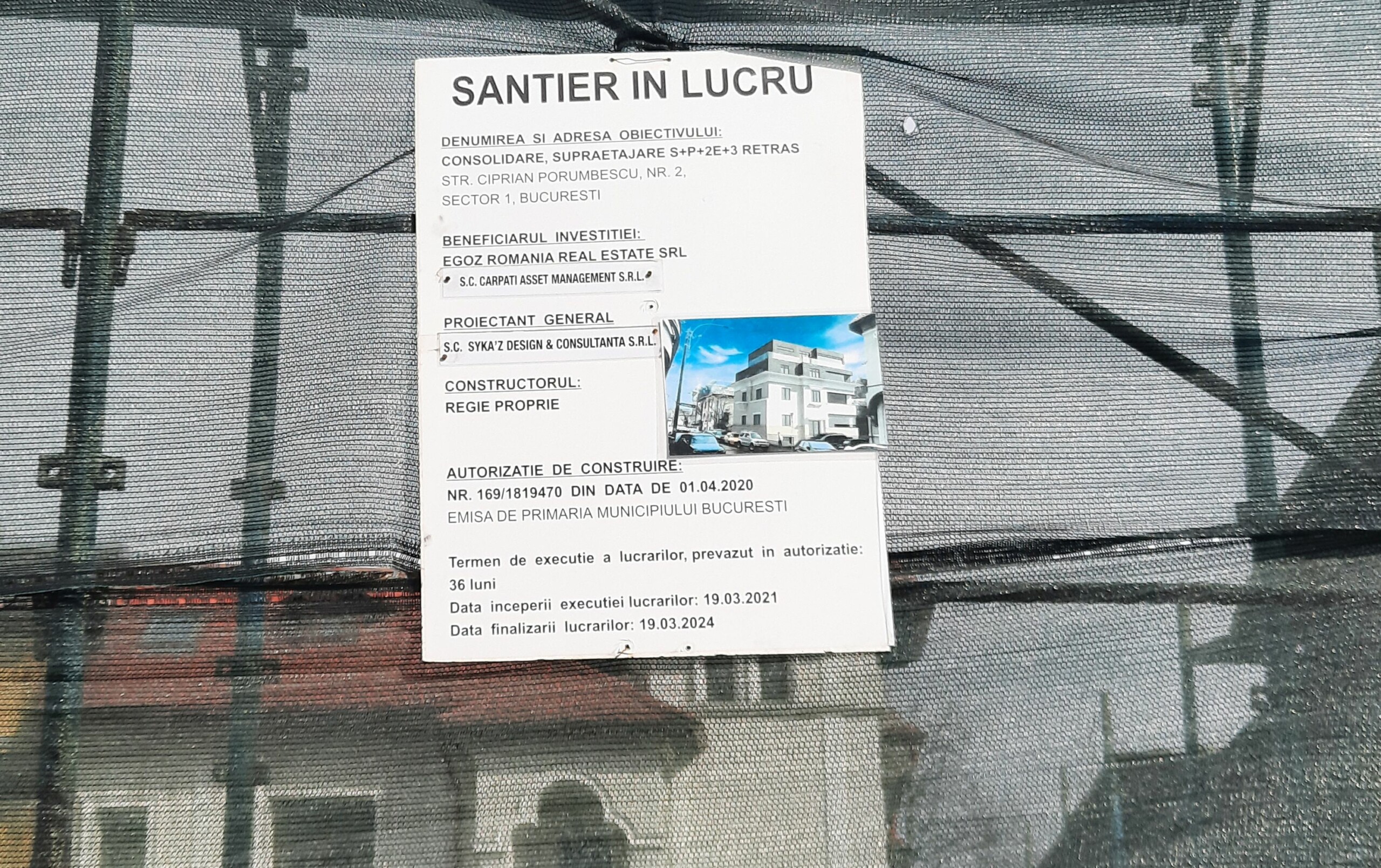

*Structural rehabilitation and added floors, 12, Ciprian Porumbescu street, Bucharest. Images: Google Earth (before) & Ș.G. (after, on March 2023)

*Structural rehabilitation and added floors, 12, Ciprian Porumbescu street, Bucharest. Images: Google Earth (before) & Ș.G. (after, on March 2023)

First, the law should clearly define the various types of operations. Thus, if you only preserve the facade(s), the procedure should be officially called “demolition and new construction, integrating fragments from the original building”. Then things could be negotiated: not in percentages, but taking into account the value of what is preserved and what not, etc. But the starting point would be that of preserving the majority, with strong argumentation for any type of elimination. In some cases, instead of imposing the preservation of some remains, perhaps it is better we accept that some houses can disappear and make room for new ones.

In order to get the chance to having such a law, specialists should assume it. Unfortunately, we find that facadism becomes acceptable or even laudable for a wide segment of architects. Evisceration works are highlighted in annuals and biennales. Even in the Mincu University, guidance is offered for projects where concealed demolition is not a particular, well-justified option, but a starting strategy.

We have some work to do here.

*before and after: Structural rehabilitation and added floors, 12, Ciprian Porumbescu street, Bucharest. Images: Google Earth & Ș.G. – on March 2023.

*before and after: Structural rehabilitation and added floors, 12, Ciprian Porumbescu street, Bucharest. Images: Google Earth & Ș.G. – on March 2023.

Zeppelin magazine #169 (spring 2023) – „Further. The Architecture Profession Transformed”