Intro: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

For over 12 years, I have nominated, as an independent expert, works for the EU Mies Award, as to use its shortened name. In 2019, I had the privilege to be part of this edition’s jury. Together with my colleagues, we shortlisted 40 projects of the 383 submitted, then 5 finalist projects, then the award. Andwe visited all the 5 works selected in the final, as well as the one receiving the award for emergent architecture.

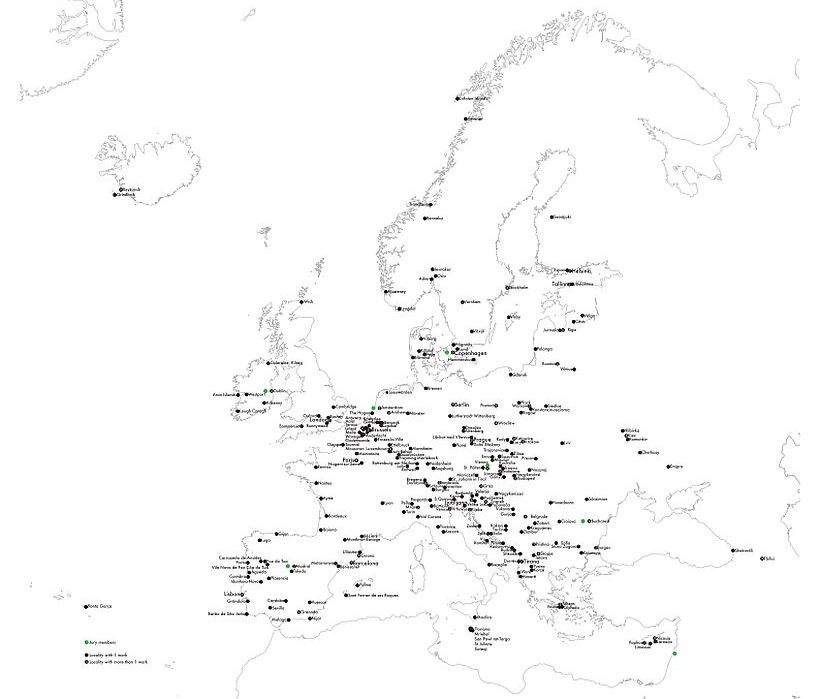

One week, 6 countries, 13 cities (because not all of them could be directly reached).

On-site discussions with architects, customers and, in some cases, users.

Architecture in all its states, and from many, many perspectives.

The Dossier started from our own experience and from the discussions within the jury, with the organizers, etc. In fact, there are two pieces brought together, as Laurian Ghinițoiu, our colleague and already an international elite architecture photographer, went on and visited all the five finalist projects. In the complex of rehabilitated dwellings of Bordeaux, this edition’s grand winner, he also talked to the inhabitants and some administrative staff.

We have attempted to talk together about architecture and about people making it, those making it possible and those using it.

A few words on the award

The first edition took place in 1988. Since 2001, it has been the European Union’s official architecture prize. The works considered are those found in and made by architects of EU countries and those having an agreement with the European Union. Switzerland fails to make this category (which is unpleasant, but is not architect-related), but very different countries, such as Norway, Serbia, Albania, Georgia, Ukraine, do.

The event is bi-annual, and the projects are proposed by experts: some designated by the orders of architects in the respective countries, others who are independent and contacted directly by the organizers, as well as by a consultative council, consisting of managers of architecture centres, architecture personalities, etc.

The jury, consisting of winners from previous editions, renowned architects, critics, researchers and curators, make a preselection of 40 projects, which, together, need to represent the diversity of approaches, programs, situations, but first and foremost a European-scale level of excellence, and then 5 finalists, of which a winner is selected. Also important is the award for a work by young architects within the preselection..

Of course, each jury builds its own criteria. These generally fall within a general philosophy, best explained by the organizers themselves (and no, this really isn’t about politics and clichés, it’s about actual firm principles: “The Prize objectives aim at promoting and understanding the significance of quality and reflecting the complexity of Architecture’s own significance in terms of technological, constructional, social, economic, cultural and aesthetic achievements.

Architecture’s significance —linked with the construction market— has a social impact and transmits a cultural message. Quality therefore refers to universal values of generic buildings, independent from their programs: the essence of things rather than their formal values.” They are also speaking of “the European city as a model for the sustainably smart city, contributing to a sustainable European economy”, as well as about the fact that “There is no good architecture without a good client. From this premise, the Prize recognises the importance of clients who are aware of the importance of quality in architecture. Their task is also highly acknowledged.”

What do the selection and awards say about today’s European architecture? A personal view

In fact, we must ask ourselves whether we can speak of a specificity of contemporary European architecture, in a world where so many architects are working in so many different places, and when the information and models are broadcast practically on the spot.

Here follows a list, an inevitably eclectic and superficial one. However, it has the merit of being based on as well on my own observations and the discussions during the jury process.

I hope it provides a contribution to a discussion on topics such as: the criteria for judging architecture in today’s world where there is no more hard canon (like classicism or functionalism were able to provide); current tendencies in our profession; and finally, if there really may be something like a contemporary European architectural identity.

1: Style is not an issue…

While the architectural world is still largely operating within the historical avant-garde’s paradigm of space and design instruments and continues to follow some of its principles, it also opposes the hard line modernist philosophy in a lot of respects: pluralism instead of radicalism; the local and the particular instead of the universal; complexity and negotiation instead of total certainty and purity; working with history instead of the avant-garde’s (alleged) total break with it; and so on. It’s this constellation of newer or older principles that shape the architectural discourse, constellation especially present in our increasingly diverse and (mostly) democratic Europe.

Style as a set of fixed features and norms becomes less and less relevant for the architectural discussion, and it certainly did not play any role in the jury’s decisions.

2: ….But beauty & poetry still are

Some might find this shocking, while others might be pleasantly surprised by it, but the fact is that noble intentions alone are not enough for a project to be shortlisted. Critical agendas, top priorities, urgent policies and so on don’t prevail over the fundamental scope and the poetics of our profession: spatial quality and innovations, logic and usability, light, materials, consistency, expression and symbolism.

3: Living history

If I were to choose one aspect in which European architecture excels that is the obsessive re-use, reinvention, and remaking of existing constructions. And this takes the form of both the respectful safeguarding of officially recognized heritage and the reinventing of modest buildings and places. Almost a half of the submissions included interventions in existing buildings or fabrics. There seems to be some general awareness of how the new is mainly a layer added on top of the older ones, and that our work must be concerned with continuity and articulation.

4: The other sustainability

Re-using instead of replacing and building from scratch is also a strong sustainability feature.. While sustainability is very much about using high-end materials and devices, the jury agreed that, more than that, it is a way of making architecture and the city: this is, for instance, about adaptive re-use, as well as urban densification instead of allowing catastrophic sprawling; design itself; sustainability and community activation; etc.

5: Added value, bricolage, broad use

Utopia as a project, and not only as theoretical reflection, is out of the picture for now. As a reaction to aestheticism and to the demise of the welfare state and the rise of ultra-liberalism, a lot of architects seem to be reconnecting to the sense of social responsibility that was so characteristic of modernism. But this no longer happens within the utopian frame of modernism, which set out for itself to change the world more often than not through social engineering; instead it happens on a smaller scale, in a more democratic way. It is becoming increasingly important to establish how your project can bring something more than a good solution to a brief; how architecture can become an instrument for adding value. One can see that in projects that start from private commissions but inject some public character into them; in the smart acupuncture and the creative low-budget re-invention of public space, as is the case in the former East European countries.

The question of programming, and not just the solution to a program, would deserve a separate article. There is a clear shift away from the “form follows function” logic. On the one hand, the majority of the selected buildings are designed to offer more than just the functional requirements (see above) but a lot of them also achieve a kind of well-designed and fertile neutrality, emphasizing spatial character and urban or landscape presence rather than a precise function; they allow for a lot of future scenarios. Function might as well follow (good) form, which leads us back to a more “architectural” form of sustainability.

In Romania and in the neighborhood

As someone from the region, I am proud that Central and South-East European projects have achieved a remarkable breakthrough this year. We will start to present some of them in the quite near future. Some of the other we already had in our magazine, such as the two selected Romanian projects – Restoration, refurbishment of the Headquarters of the Order of Architects of Romania – Bucharest Branch by STARH and Occidentului 40 apartment building by ADN BA. There is a good trend going on, I think, even if the lack of competitions and public support for architectural quality really makes it a tough job for our societies and colleagues around here.

Special thanks

To my colleagues in the jury: Dorte Mandrup (Chairwoman), George Arbid, Angelika Fitz, Ștefan Ghenciulescu, Kamiel Klaasse, María Langarita, Frank McDonald. I was a privilege to be in your team – and this is not a polite formula.

To the EU Mies ward team, for the whole spirit of the event and for the combination of kindness and professional, ethical and cultural standards. Special thoughts for Anna Ramos (Director), Ivan Blasi, Jordi García, Anna Bes.

The Dossier is published in Zeppelin #154 (summer edition, 2019), to be launched on Friday, June 21, 18:00 at the Central University Library ”Carol I” of Bucharest.

*Fb event

Photos:

1. Cultural Center and Auditorium, Plasencia, Spain©Laurian Ghinițoiu

2.Map of the location of the 383 works in 238 places.

3. BAST: E26 (school cafeteria), Montbrun-Bocage, France ©Ștefan Ghenciulescu

4. De Vylder Vinck Taillieu: PC CARITAS, Melle, Belgia ©Laurian Ghinițoiu

5. Brandlhuber+ Emde, Burlon; Muck Petzet Architekten: Lobe Block, Berlin ©Laurian Ghinițoiu