The scale regeneration of an entire romanian city, and not of an energic metropolis, but of a post-industrial town, is the subject of a Dossier coordinated by Lorena Brează & Mugur Grosu and published in Zeppelin magazine no. 166 (summer 2022). We have undertaken an extended analysis, with detailed interviews, dates, etc., because Reșița – a centre of modernity ever since the 18th century, then subjected to brutal de-industrialization – is an example of rebirth. Unique in Romania and valuable enough to serve as an international model, even if the process is still underway. Here is the first part (the second part – here):

How to prepare and achieve change. Urban strategies and projects

Intro, interviews: Lorena Brează

Photo: Farkas Pataki, Daniel Pușcău, MKBT, Munții Carpati/ Radu Ștefănescu

There is a lot of talk about Reșița lately – a lively city, with a rebuilt public space and several regeneration strategies. Not all of us remember for how long it stood in the shadows and suffered from deindustrialisation, one of the many desperate cases in the country. The rebirth we are beginning to see today is not a miracle, a strike of luck, or an accident. We are talking about Resita as a model of regeneration, of cohabitation between history and new strategies, but also as a city that capitalizes on its potential in all directions. And the transformation is still in its infancy.

I went to high school in the heart of a neighborhood that was difficult for me to recognize today – Lunca Pomostului. Back then full of booths, shops and bars, a lot of wild vegetation and houses whose facades were hard to discover, the neighborhood was, for us at least, just an area of passage to more important parts of the town. Now I found a lot of light here among the houses, streets free of visual noise, and even lively squares among the blocks of flats, in places where I expected the least. In fact, from one of the windows of the high school I realized that I can see, through an orderly and lively public space, to the other side of the valley where Resita stretches.

Its inhabitants are divided into those who look nostalgically at the city, remembering its industrial prosperity and those who enjoy it today, admiring and visiting its surroundings, nature, lakes and mountains that complete the valley in all its directions. But today Resita is in a transformation that has amplified in recent years in various ways, from big to small, in one of the largest projects the town has known, from urban and industrial regeneration strategy, space public and, and last but not least, orientation towards regeneration through contemporary art. In order fot this to happen, specialists in various fields have been brought to the table from the very beginning, and this is one of the key elements of the project whose results we are already beginning to see. As trivial as this may seem, it is worth mentioning in a country where administrations are struggling to bring the right actors to the table.

I talked to Rudolf Gräf and Paul Buchert about the Lunca Pomostului neighborhood and the interventions in the public space carried out by the Vitamin Architects office in the area, the process behind such a project and the way people received these interventions. With Marina Batog – urban economist and co-founder of MKBT, the studio with which the municipality collaborated in thinking and implementing urban regeneration strategies – we talked about the city’s regeneration directions, starting from the first sketches of the project, started 6 years ago, in a permanent discussion with a mayor wiling to chang and better his city. (Lorena Brează)

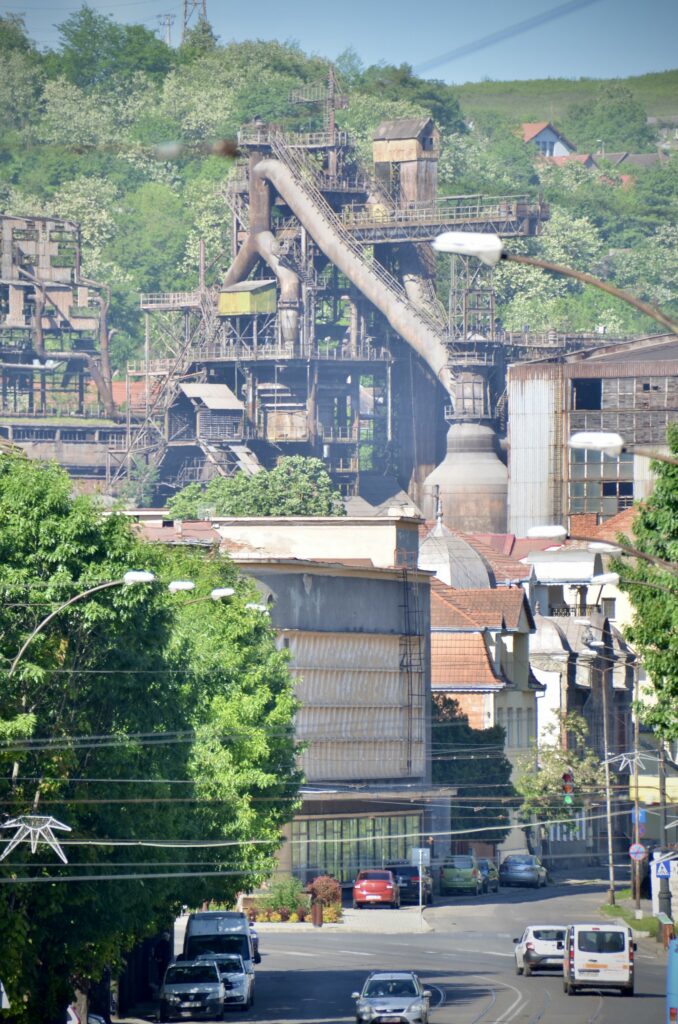

*A fabulous industrial past and modern heritage. Photo: © Daniel Pușcău, MKBT & Munții Carpati/ Radu Ștefănescu

Macro scale. Interview with Marina Batog, MKBT

How did you start sketching the strategy for Reșița?

We arrived in Reșița in 2016, a few months after Ioan Popa took over his first term as mayor. We hoped to work on the urban regeneration of marginalized neighborhoods, which we managed to do in the years that followed. We facilitated the formation of a G.A.L. (Local Action Group) together with Reșița City Hall for accessing European funds for urban regeneration projects in areas severely affected by poverty, degradation of the urban environment and poor housing. We developed the urban regeneration strategy for these neighborhoods (Mociur, Dealu Crucii and others), which was approved for financing with 7 million EUR EU funds. The projects related to this strategy have been implemented only for 1-2 years.

*Dealu Crucii – urban marginalized area

*Dealu Crucii – urban marginalized area

However, we realized that we can do other projects together, in parallel. Importantly, the mayor realized that abandoned buildings and land belong to the city, therefore, they can be used to the benefit of the community, even if they are owned by other entities. This thinking is valuable and rare among mayors in the country – there are many cities where such latent spaces exist and are not taken into account, although the need for land exists.

How did you approach the subject of industrial regeneration and what is going to happen in Resita in this regard?

In 2016 – 2017 we made an inventory of these sites – 19 large industrial sites – along with a real estate analysis on the residential, commercial and industrial segments. Subsequently, we decided together with the mayor to focus our efforts on an area with the greatest potential for reconversion – Mociur area, including the perimeters towards Triaj and Valea Țerovei – a very well positioned area, which connects the two parts of the city, the old town and the new city. On this industrial site we discovered over 20 plots with different owners – because as the plants were privatized, the land was dismantled, fragmented, some confiscated by AVAS (Authority for State Assets Recovery) on account of the debt they had, others sold for the recovery of scrap metal from the remaining halls. The challenge was how to make such an area attractive to a developer and feasible as an investment project.

More than a year of work followed to identify land and property boundaries, to think of promotional materials and presentation kits for investors, to design a communication plan for investors, residents and visitors, to develop a presentation page of Resita for investors – www.investinresita.ro. And from 2017 we started going to fairs and conferences to promote the city and to send information and materials to embassies and consulates in Romania. The mayor is a charismatic, visionary speaker, we made a good team together. So, Resita started to become known and take awards at profile events, and investors became interested in these spaces.

*Former industrial area of Mociur. Seen here, the cooling tower that was saved from the demolition of the plant. The tower will become the centerpiece of a square within the urban development of the area © MKBT

*Former industrial area of Mociur. Seen here, the cooling tower that was saved from the demolition of the plant. The tower will become the centerpiece of a square within the urban development of the area © MKBT

What is the timeline of the development of this big project in the Mociur area, how did it start and what does its strategy look like?

The Mociur – Triaj – Valea Țerovei area is very large, there are over 100 ha cumulated – the site has the potential to host one of the most interesting integrated urban regeneration projects. Here, in the Mociur perimeter (about 60 ha), where the UCMR steel smelting and foundry section was located, the developers attracted in 2018 bought the fragmented land piece by piece, and will build a mixed project on it – a mall, a hotel and an aquapark, offices and housing nearby, over a time horizon of 10-15 years. This new development will also generate a new axis for crossing the city.

*Mociur – urban marginalised area

*Mociur – urban marginalised area

The perimeter that represented the former colony of workers working on the Mociur platform, now a notorious ghetto area of the city, is transformed by the urban regeneration projects financed with EU funds through the LAG, mentioned above. The perimeter from Valea Țerovei, organized and promoted as an industrial park (about 30 ha), has already attracted new investors in the last 3 years and is more recently managed and promoted by a dedicated local development agency. And the perimeter from Triaj is planned to host a new county hospital, with European funds.

Locally this entire strategy is less known, as the discussion mainly centers on the mall project. But even so, we realized that Resita was the only county capital without a commercial complex that would bring together large retailers. We understood and analyzed this investment opportunity, and this is also the reason why shortly after the first conference we attended and Mayor Ioan Popa promoted the Mociur functional reconversion area, the first negotiations with the developer started. The municipality played a very active role in bringing the identified landowners and developer to the same table. And especially in carrying out negotiations with AVAS, which owned part of the lots in the area, in order to convince them to put them up for sale. This effort is lacking in other cities in the country – where large industrial sites, centrally located, lie abandoned while public or private funds go to peri-urban greenfield development.

It took 2-3 years and a lot of perseverance until the site could be bought and merged, to become viable for the intended conversion project. The Urban Area Plan was recently approved, and at the moment, the municipality is going to make a new access road to the area, following a preliminary traffic study. In the following years, the commercial functions, the horeca and a water park will appear, designed to be connected directly with the Văliug – Semenic ski area. Therefore, only in another 4-5 years will these results begin to be seen.

How did you form the team for the project and what were your needs in order to start this process here?

On our part, of MKBT, we brought as a team and collaborators a mix of urban economy thinking and city marketing, a lot of facilities for consultations and participatory processes, a lot of fieldwork, experience in strategic planning, GIS skills, urban engineering , spatial planning. We are often associated with an office of architecture and urban design – we do neither of them, but the work of preparation, concept, consultation that precedes or accompanies the projects of architecture and urbanism.

From the mayor’s part, there was a whole background revolution, necessary in order for the city to be able to support large, visionary, long-term projects. Mayor Ioan Popa set up a new team, rethought the organizational chart and the budgets necessary to start these processes, always focusing on attracting competent people.

How do the inhabitants see the city?

In parallel with the efforts to map and think about functional reconversions of industrial sites – ‘hard mapping’ – we also carried out a process of ‘soft – mapping’ – we identified and interviewed the networks of people that matter in the city. We consulted local organizations and went on the field to understand what perspectives citizens have, what needs for new functions exist in the local community. We also did focus group interviews on age segments – young people, adults with children, and the elderly, to understand how they relate to the city and what their needs are. Young people, for example, are disconnected from the industrial history of the city and the situation of abandoned sites, about which they do not know much. Older people are nostalgic, but somehow more confident that a small town like Resita can be glorious and attractive, because they grew up in a Resita that could be like that.

How can Resita attract people in the near future?

We are talking about an “the chicked or the egg ” situation. You can’t attract investors if there are few people, a declining demographic. And you can’t really attract and retain people if there are few investors, too few professional opportunities.

In these cities that have been centered on 1-2 large factories, there is still the nostalgia of a large employer who would give work to all those who are not currently employed and would solve the problem of unemployment. In reality, a city like Resita would have difficulty integrating an investor that would open 500-1000 jobs or more from a fire. There is a need for a variety of types of jobs, in more attractive and better paid fields. This can be done by attracting more small to medium-sized investors, on the one hand, and by supporting local entrepreneurs on the other hand, to grow their business and be able to hire more.

What Reșița City Hall does well – and with our contribution, but especially with their merits – is to welcome investors as well as possible. Land and hall sheets available, labor force data, dual schools to train and recruit young people, competent support in permits, an honest, involved, solution-oriented discourse.

There is a great potential to attract young people from the surrounding villages, they come to high school / vocational school in Resita and are attracted to stay here. The mayor’s office has rehabilitated or is rehabilitating with EU funds all school units in the city, including boarding schools for rural students, and has developed a system of scholarships with public funds and from potential employers.

What would be, from your point of view, the profile of the person who stays in Resita and lives his/her life here, once these projects are implemented?

Let’s look at the city of Resita as a ‘product’ and understand its user, or consumer. The profile of the ‘consumer’ of Resita is a person who appreciates a city with a slower pace, easy to travel, surrounded by nature, but with attractive urban facilities and a low cost of living. If you live in Resita, you practically live under the edge of the forest, but you have good schools, tennis courts, swimming pools – well-developed urban infrastructures and services, much more affordable than in the bigger cities. It seems to me that there is a market for such a product, people who would always give the state in traffic an hour a day on a walk in the woods, assuming without regret the disadvantage that you have less nightlife in the city and only a theater instead of ten.

A city does not have to be big, demographically and economically, for the people who live in it to be happy and fulfilled. The stake here would be about how to increase the income level and quality of life of those who live in Resita, and how to make sure that those who live here do so as a personal choice, not out of coercion or failure to leave. Reșița must become “a city of choice”, bringing together those people who are happy with the choice to live there, proud of their city, satisfied with what it offers. It is not necessary to increase the population by 5% as an indicator of success. It is more about generating an alignment between the intentions and individual needs of residents and the direction in which the city is heading.

How do you see this collaboration in the future and what other projects are in plan for Reșița?

We want to work long term in Reșița. The processes of urban regeneration extend – from idea to result – over decades. We aim to continue working on both areas affected by urban poverty and on urban areas that will undergo extensive reconversions and redevelopments. We gradually migrated from a model of working directly with the municipality, as a consulting service provider, to position ourselves as a partner and apply, through our NGO, to funding together. We intend to work more and more with other local actors – NGOs, developers etc. Our vision is to build a network of partners to co-create and implement urban regeneration initiatives together, in the form of an urban innovation laboratory. We will continue to act mainly on three topics: housing, industrial heritage, and the connection between the city and nature.

Info & credits – Urban Strategy:

MKBT Team: Marina Batog, Ana-Maria Elian, Mihai Șercăianu, Bogdan Suditu, Andreea Bahrin (colaborator/collaborator)

*Aerial view of the city and its surroundings. In the cneter, the square with the cinetic fountain by Constantin Lucaci © Munții Carpati/ Radu Ștefănescu

*Aerial view of the city and its surroundings. In the cneter, the square with the cinetic fountain by Constantin Lucaci © Munții Carpati/ Radu Ștefănescu

Micro-scale. Transforming public space in Lunca Pomostului. Interview with Rudolf Gräf and Paul Buchert

What was the strategy for reconfiguring the streets in Lunca Pomostului?

Lunca Pomostului was built in the 50s and 60s, being a neighborhood of social housing, so the streets the plot and the buildings result from a centralized process that was thought in one piece. This allowed us to give the neighborhood visibility as a whole, so as not to be perceived as a part of the city without an identity. One objective was to adapt the street space to the functions around it. I think public space in Romania suffers because it is thought strictly as a car flow that does not look at what is happening adjacent to it. We tried to customize the profile of these streets in relation to the adjacent functions – for example one of the spaces has a school where we managed to introduce a square. The street on which the school is located is slightly crooked, in order to stop you from speeding, which has been a question mark for many people – why isn’t the street straight? The rehabilitation contained 6 streets, making the connection between the 2 major traffic arteries of the municipality that border the neighborhood on two sides. We proposed a scheme to reconfigure traffic by introducing one-way streets, which allowed the expansion of areas dedicated to pedestrians, cyclists and green space and optimizing individual traffic in terms of consumed space.

We quickly understood that we can get a high quality of the public space if we change the traffic system in the area, and here it was very important that the municipality, especially through the mayor, was open to these changes – some very unusual for Romania. Together with the administration, we managed to achieve solutions to increase safety by reversing the direction of travel for the bicycle system compared to the car system. This is still a rare solution in Romania, one that encountered a lot of opposition initially.

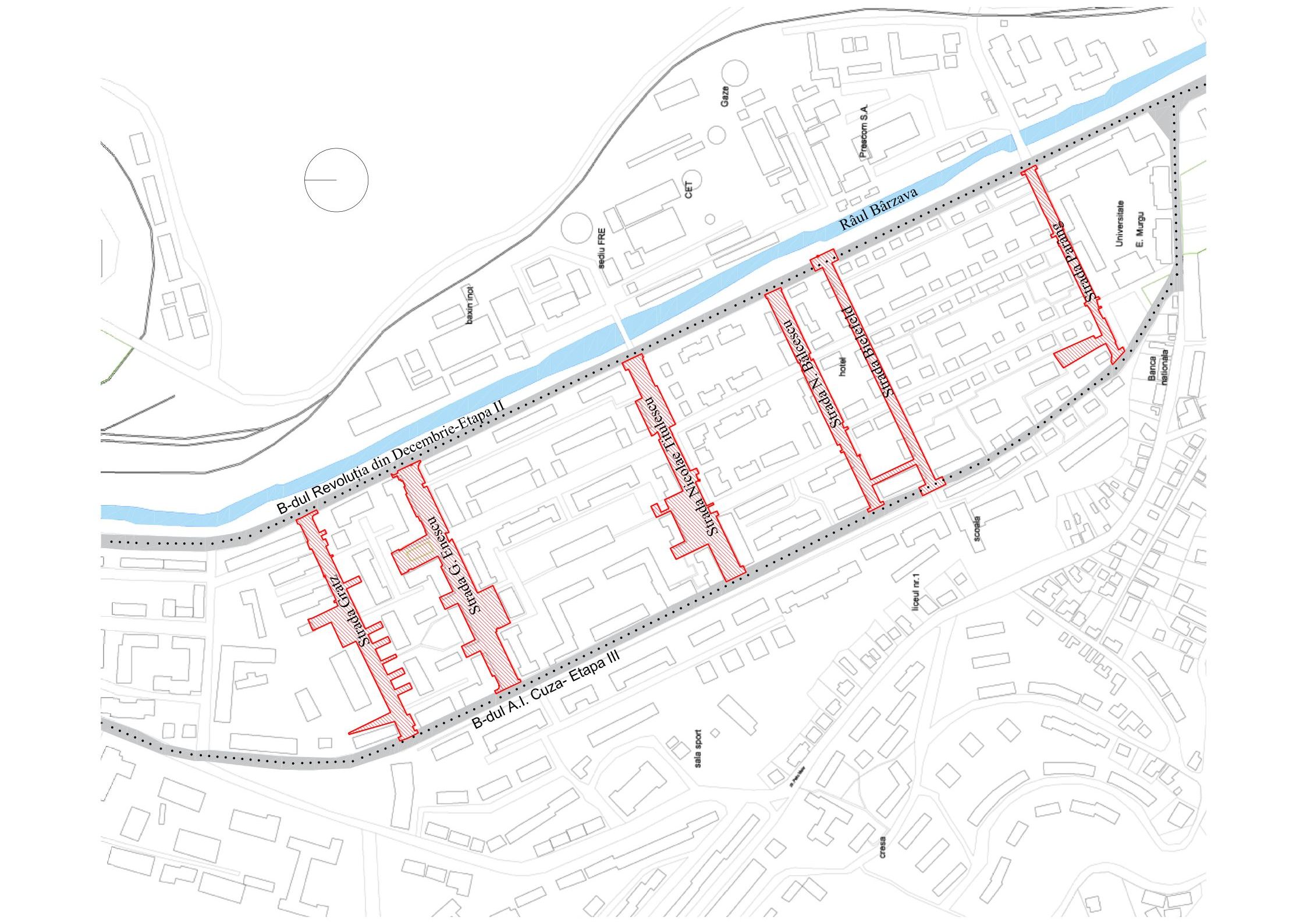

*Vitamin Architects:urban re-design for six streets within the Lunca Pomostului neighborhood: general plan in the urban context. The six streets connect two major circulation axes – the boulevards “Revoluția din Decembrie” and “A. I. Cuza”. The project is part of the town’s mobility strategy. Some of its essential elements are accesibility, the creation of attractive public spaces, traffic calming, the emphasis on pedestrian and bike circulation, a new lighjting system, the integration of parking and networks

*Vitamin Architects:urban re-design for six streets within the Lunca Pomostului neighborhood: general plan in the urban context. The six streets connect two major circulation axes – the boulevards “Revoluția din Decembrie” and “A. I. Cuza”. The project is part of the town’s mobility strategy. Some of its essential elements are accesibility, the creation of attractive public spaces, traffic calming, the emphasis on pedestrian and bike circulation, a new lighjting system, the integration of parking and networks

*Detailed plans of Nicolae Titulescu Street (up and middle) and Bielefed (bottom)

*Detailed plans of Nicolae Titulescu Street (up and middle) and Bielefed (bottom)

Overcoming these first reactions was also possible due to politics – they understood that this transformation leads to the good of the whole neighborhood, and that the street space is public space, subject to the same ambitions and needs of quality, inclusion, accessibility and safety – therefore, there should not be a difference between them in terms of the ambitions we have for them. The most important thing was to increase this ambition for the street space and to exceed the satisfaction of a well-paved road.

What can you tell us about the process behind the project?

When you work with public administrations you know that it is a difficult process, there are many constraints related to procedures. Here we were lucky to have a very good collaboration, but we would have liked to have more participatory component in the process. A very important thing was related to the technical documentation – already in the initial stage we relied on a very large detail of the solution – we defined the technical data sheets for the products, which was not necessary, but we did it just to make sure that in the next design stage anyone who would take over the project (at that time we did not know we would do it) will be forced to go for quality solutions.

*Previous state of the food market

*Previous state of the food market

*Present state of the food market

*Present state of the food market

How did people react to these changes in public space?

The reactions were very diverse. We did not quantify them organized, but they ranged from people who go especially to walk there, because there they feel civilization and a pleasant environment, to people who were glad that trees were planted in front of their house, people who are happy that cars don’t go so fast anymore, to people who say they can’t stop their cars where they want anymore. You have to be careful how you drive. The problems came amid car traffic and parking restrictions. However, the number of parking spaces is the same as before, only now you can not park where you want.

Another important point was to integrate all the necessary facilities, from garbage cans to selective collection, to public lighting with different types of light, squares and areas with street furniture where small fairs or markets of different kinds can take place – and this is a trivial thing, which should always be taken into account. I think that in the end the fact that the public space becomes so diverse gave everyone something in return, even if it took some things from some people – for example the fact that they can no longer drive with 50 km / h in the neighborhood.

*Vitamin Architects: Urban design, Nicolae Titulescu Street © Farkas Pataki

*Vitamin Architects: Urban design, Nicolae Titulescu Street © Farkas Pataki

So, these 6 streets give the structure – a work rule and an ambition – and this is very important for the city. Once the ambition is built, things can be built on it, with the same level of quality. At the same time, we don’t necessarily think that for every square meter there should be a designer – from here on the municipality can work by itself, following the given direction.

Reșița as a balance in its network of public spaces has always been in the situation of having an oversized center – there was no other public space other than the center. We believe it is very important to recover the street itself as a public space, and this is true for many cities in Romania.

We hope in time that in Lunca Pomostului we will have a “downtown” – an urban structure of reasonable size, with urban life in which to have a mix of activities. Once connected to the corridor on Bârzava, they can easily connect to the central area, and can offer an alternative to a weekend walk. The fact that the administration emphasizes the quality of public space is very important for a city that has not been known for this.

What should happen in the Reșița in order for people to want to live here?

I think the project on the Mociur platform is important because it shows the potential of this industrial area that has long been ignored or seen as a ballast. And I think that for the city the mountainous Banat area has an exceptional role – it is important to take advantage of the tourist potential that is there.

I think it would be important to have, beyond the level of the narrative, an experience of the industry / industrial spaces of Resita – this would be a point of attraction for many people. And this in combination with what is happening with the funicular – where there is a refurbishment project – I think it would connect things very well. This is somehow in the genetics of the city – Resita as an industrial city would not function without a network of transport and export of resources, water channels etc. Resita was just a node of a network. I think that things need to be brought into a network that can now be exploited, including tourism, and this can also be a basic element for the local identity, as a marketing element. But beyond social policies, the city itself needs to update local mobility – and I know there is a project to restore the tram line – these are good opportunities to generate a modern accessible functional public space, adapted to climate change. This is also the reason why we chose light colors for the paving of public spaces, for example.

What should be done to increase the quality of public space in Romania?

In the West, the discussion about pedestrian-oriented public space came from civil society – from people who said, “I can’t and don’t agree to live in a polluted environment all my life.” As long as this pressure does not increase in our country, few administrations will act in the right direction. On the other hand, I believe that over time there will be a greater interest in universities in this area, we currently have little research in the area of the impact of mobility on quality of life. But as long as the simple interest of a resident is to park his car under the window, it becomes quite difficult to do more in this direction without a smart change-oriented effort.

There are several things that should be done to have a quality public space in Romania – it’s a mix – on the one hand the pressure for quality should come laterally, from the professions, on the other hand it is needed from the area of certain European policies that finance certain things. For example, the roads for cars were not financed for Resita and then the widening of the public space dedicated to pedestrians became extremely interesting. Therefore, these mechanisms can play an important role.

I think we need to be able to imagine our cities differently, better, more captivating, more friendly and I think a big problem in Romania is the fact that we can’t even imagine changing the environment we live in, much less in terms of a social consensus. But this is changing, successful examples will further open your appetite for friendly streets and cities that help you instead of getting in your way, sometimes literally.

Info & credits: Public space regeneration:

Period: 2020- 2021

Area: 28 000 m2

Architecture: Vitamin Architects – Cosmin Sandu Bloju, Paul Buchert, Rudolf Gräf, Olimpia Onci, Arh. Cristina Paralescu, Arh. Alexandra Sabo, Alexandru Todirică, Arh. Alexandra Trofin;

Roadworks: Coso Cons – Florin Coșoveanu, Andrei Szabo

Electrical Installations: Atena Proiect Consult – Cornel Prodan

Optical fibers: Electroechipament Industrial – Attila Olasz, Marius Barbu

Structure: Plan Design – Bogdan Trifa

Water and sewage networks: Pro Wasser-At – Simona Fântâneanu

Landscaping: Vitamin Architects – Cristina Râmneanțu

Lighting studies: Blaser – Bogdan Sere

Geotechnical study: Scenconstruct – Adrian Centea

Fountain project: Fountain Design

Constructor: Constructim

Related article: