Republic of Architects is led by Emil Burbea, Oana Iacob, Radu Ponta and Alexandra Zăgan. They are no strangers to Zeppelin, in very different ways: to their designs of minimal living prototypes, to the transformation of their office space in an open place, to apartment buildings or theoretical texts on transition urbanism. Most articles shared the context – the Bucharest central area – the combination between practice and the critical overlook on the city, the space, urban life. For this article, they take us on a ride outside the downtown.

The house in the „Bucureștii Noi” neighbourhood raises the issue of densification in semi-urban areas (or former suburbs, the urban neighbourhoods of today): how does one propose a modern dwelling on a small plot of land? How does one participate in an urban future without cancelling place-specific qualities, such as transparency, intermediary spaces, and the friendly scale?

Project, text: Republic of Architects

Photo: Dafina Jeacă

Too little and too much. A game of clues

“L1e – Individual dwellings on sub-sized plots of land with/without municipal networks” is the regulation for the city’s peripheral areas. This qualification is first and foremost confirmed map-wise. Yet, on the map of Bucharest, the eccentric position of these areas against the historical and geometrical centre of the city suggests a false equivalence: first, because of the city’s unequal development, favouring the north side, and second, because the time distance to the centre is related to the actual development of infrastructure (quite different from a seemingly unoiform geometry. So, despite the identical urban planning regulations, Bucureștii Noi will never be so peripheral (or identically peripheral) as the L1e areas in Rahova, Ghencea, Berceni or Colentina.

Psychologically, the designation of L1e areas as ‘peripheral’ is drawn from the very elements which constitute the name of the area – ‘sub-sized plots of land’ and ‘with/without municipal networks’. Sub-sized for what or for whom? It seems that when the regulations deemed these plots as being much too small, they didn’t take into account the (real life) development through the individual improvement of dwellings.

And then, starting from the premise that the regulations for these areas were devised in the sense of dwelling development and that their particularities require a distinct approach, how are urban planning indicators different from other dwelling areas (namely the ‘detached and small collective’ – L1 and L2 types)? Urban planning conditionings propose the same lateral and rear recesses, and the height regime is negligently different. The POT (land occupancy percentage) and the CUT (land use coefficient or plot/area ratio), differentiating between the L1e and other areas, suggest that a larger percentage of the plot can be occupied here by a construction but then less square meters can be built, as compared to other areas, where more can be built, but on a smaller area of the plot.

*site plan showing a development model based on a maximum foor print shile respecting the present regulations

*site plan showing a development model based on a maximum foor print shile respecting the present regulations

If we develp the model to the maximum that the market aspires to, within L1e there will result less unbuilt space per plot (40 as compared to 55%), partially occupied by the same access paths and parking spaces. Adding the eternal minimum lateral recesses of 3 and 5 meters, it results that within the L1e periphery, the courtyard is smaller than ‘downtown’, while being divided into exactly the same front, on the side and back yards, that seem to represent, in the regulators’ vision, the main building blocks of the city. Not only do these undersized plots bring on smaller houses, but the green area is also smaller, and that happens precisely in those peripheries where too much is built on too small plots, an development that started, ironically, with people’s obsessive wish to escape the city and get as close to nature as possible.

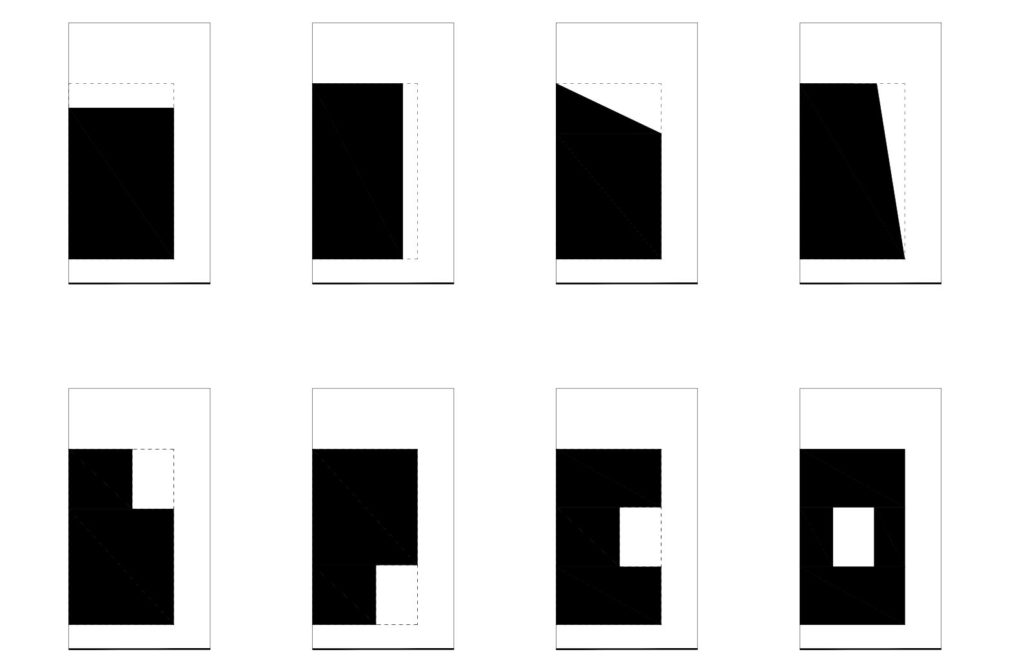

*Variants of ploto ccupation. The built footprint remains the same but the unbuilt space is organized in various ways

*Variants of ploto ccupation. The built footprint remains the same but the unbuilt space is organized in various ways

The courtyard: from leftovers of the plot to the heart of the house

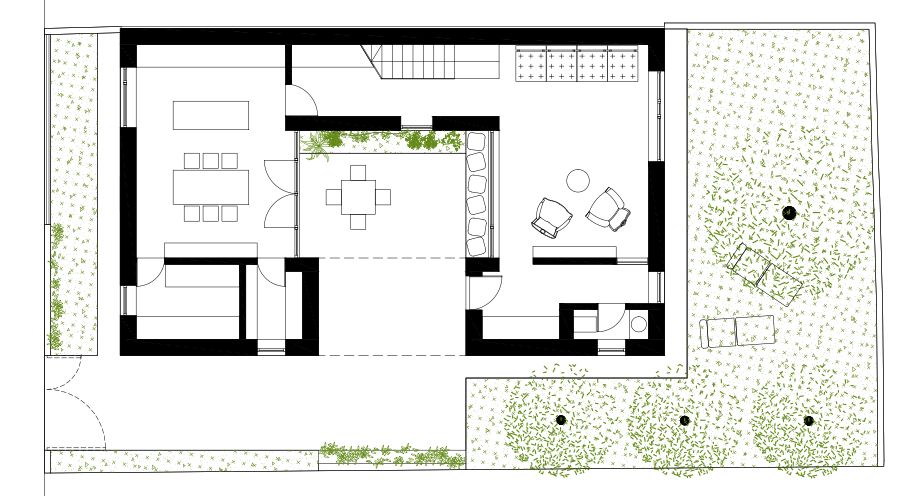

We had to design on a small plot in Bucureștii Noi neighbourhood (an early 20th century development in the north of Bucharest that has undergone significant densification in the post-socialist period). Standing on a design theme that was not into fully exploiting the land’s commercial potential, our approach attempted to search for a different meaning that the unbuilt space of the plot could have in relation to the interior of the house, one adequate for the modest dimensions of the plot. [The plot was 260sqm, but not due to fatal sub sizing derived from the plot scheme, but through the subdivision of a larger plot]

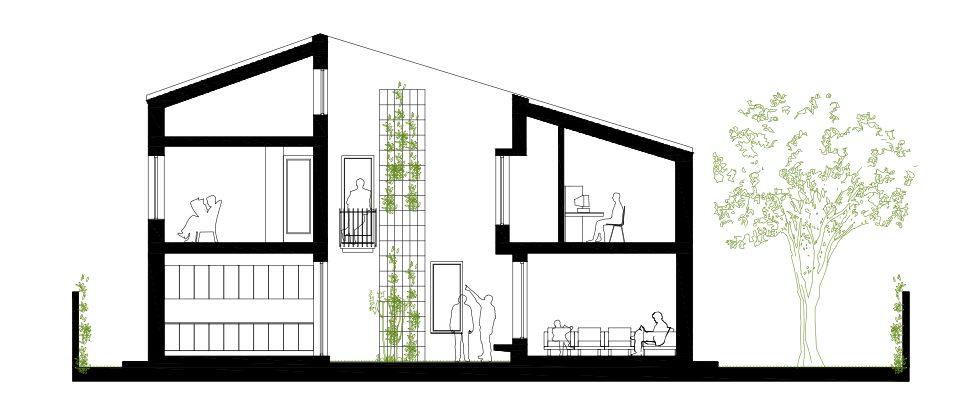

Swelling the house out to the buildable limits, an extra built space resulted. We eliminated the part at the centre of the house (and plot) and we opened the empty spaces thus obtained, towards the outside, to the side and height-wise: a patio.

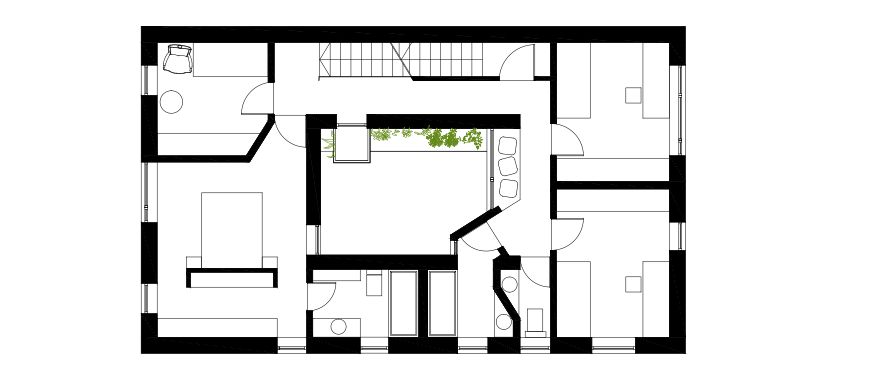

The house enfolds around this empty space and communicates with it on all levels, through the openings of interior spaces, allowing in-depth cross views.

These perspectives trick on the perception of the house’s actual dimensions [the ground floor has a built area of 100sqm, and the upper floor has 110sqm] as they remove the spaces from each other, interposing not just a physical distance, but also a psychological one, given by crossing an exterior space.

The depth that the patio introduces in how spaces are perceived is also translated into a playful experience, whose sign is the interior balcony, the only balcony to a dwelling aimed at taking as much advantage as possible of the unbuilt spaces on the plot.

In this respect, on the ground floor, the patio has no fixed usage – it can work as an extension for the main access space, as a dining place, or as an open-air drawing room.

This open and yet enclosed space at the core of the plot becomes an ineluctable space of dwelling, an alternative that is more protected than the lateral and back yards, but also more intimately linked to the actual use of the house.

Reversely, focusing the activities which the patio requires, releases one of the three traditional courtyards of the plot – the rear one – from the pressure of being used, and transforms it into a landscaping garden to care and admire, rather than one dedicated to current usage.

Living focuses the greatest intensity at the core of the plot, without, however, closing-up towards the neighbours and the street, who receive more green space. The house doesn’t contradict the L1e regulation, but rather hijacks it by its use of unbuilt space.

Info & credits

Authors-co-authors: Emil Burbea-Milescu, Oana Iacob, Radu Tudor Ponta, Alexandra Zăgan, Răzvan Delcea, Alexandru Mateescu

Office: Republic of Architects

Collaborators: Rantech Proiect, Vest Klima Instal

Adress : Bucureștii Noi (neighborhood), Bucharest

Total built area (sqm):287.42