In September 2016, Zeppelin moved into one of the top innovative buildings produced in Romania in the last years. We wrote about it, promoted intensively. Now we change the role of the critic to the one of the dedicated user.

The House is integrally built from a locally developed thermo- and hydro-insulating concrete, and the result of a partnership between open and responsible clients, an architect with vision and courage and strongly involved construction partners.

The house came out both radical and friendly, sustainable in a very particular way, internationally relevant and yet with a Bucharest flavor. Starting with his year, the Association for Innovation in Architecture initiated a program (supported by CHR România) that transforms it into an office space for organizations that deal with architecture and the city, as well as a place for events and culture.

Bogdan Gyemant-Selin, the designer of the building, also works here now, living with and developing his own experiment. We, the Zeppelin team, also settled in, feel already quite well and start thinking about public events. And we promise to tell you at some point, together with Bogdan and A.I.A., about how the project project works and grows.

About the project

Architect: Bogdan Gyemant-Selin

Text:Ștefan Ghenciulescu, Cosmin Caciuc

Photo:Cosmin Dragomir

Teodora Zăbavă and Mircea Toma deal, together or separately, with very diverse things: from press freedom and democratization to minority rights and disadvantaged people, from environmental protection to community education programs. At some point, they became the owners of a lot of only 213 m2 on a street that, before the war, had been part of the merchants’ quarter next to Bucharest North Station.

Now it is hidden behind the barrier of blocks built in the ’60s. On the lot there was a ground floor building, ruined beyond recovery (having been built from the leftovers of the war bombings).

The two have come into contact with the architect Bogdan Gyemant-Selin and asked for a project of a space for entertaining 30–35 children aged between 1 and 5, accompanied by their parents, a space that should be at the same time playground, and a place for socializing and alternative education; a friendly place where children and parents could feel good, and far from the institutionalized educational spaces and hysterical nature of the commercial playgrounds.

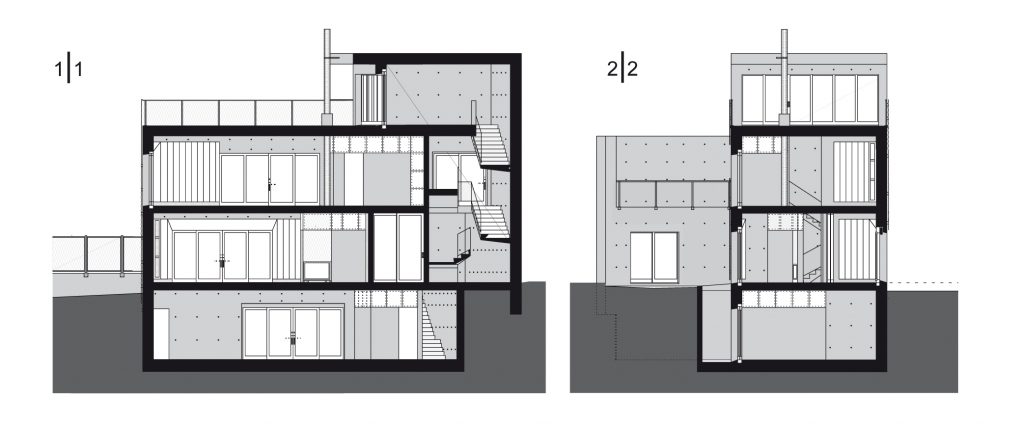

Its modest size and its intentionally domestic nature led naturally to the “house” denomination. It required many different spaces, open, but also easy to separate, technical and circulation cores and a rich and differentiated connection with the garden and the city. Flexibility was another key word: the house had to fulfil the desired functions – playgrounds, learning ground and sleeping spaces, plus a place for the parents in the basement which opened into an sunken courtyard; but it also needed to be easily converted into office space and workshops for creative functions and even into a proper home; an efficient, variable, friendly and obviously “green” space.

And very importantly, all this had to be possible within the limits of a budget that did not exceed the price of a correct conventional construction.

What is a truly sustainable house? A research and a criticism of the prevalent paradigm

The first ideas and discussions had been about a wooden structure. This proved impossible, because in Romania, in dense urban contexts, something like that is not allowed by regulations. Once the wood was removed from the discussion, the architect and the clients explored together a number of solutions. The discussion had shifted from a primary level – that of natural materials – to that of a deeper sustainability related to, for example, the idea of recovering some of the elements of the existing building. Therefore, they studied the use of structural sections from a demolished factory; then train rails; finally, they explored the creation of a concrete made of crushed debris. None of these ingenious possibilities proved viable, simply because the law requires full homologation (that is, official accreditation after standardized experiments and administratively cumbersome processes) for recycled materials.

The last attempt to preserve something of the recycling idea was to build a frame from new concrete, but to use for the walls recovered bricks, including from the old house that had been demolished. This option would have passed various approvals, even from the fire brigade, but not the thermographic analysis: the problem of building physics, poor isolation but especially thermal bridges.

The problem could not be solved, but at least mitigated, with the compromise of a completely new construction, with concrete structure and other extra materials for partionining and insulation. This is the usual way of doing things today, the vast majority of buildings in Romania (and in Europe, in fact, except maybe Scandinavia and some parts in Switzerland and Austria). Usually in such cases you try to replace the shortcomings of conventional structures through the clutter of finishes and equipment: a super-insulation of the walls and openings in the first place, and then performing installations for heating and economic ventilation, possibly equipment for solar, aeolian, geothermal energy and so on.

This was quite different from the initial dream, and therefore a moment of crisis, but also a chance to rethink the concept of sustainability. Let’s remember: green architecture began as a kind of adventurous alternative, then it stirred interest, became increasingly relevant with the spread of an overall public awareness, especially with the disaster of the increasingly obvious global warming and now it turns into a norm, a set of measurable standards and procedures for all buildings, usually marked by esoteric initials: leed (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), breeam (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Methodology), zeb (Zero Energy Building) and so on: ecology built-up by following standards. In certain countries and following a more sensible approach, sustainability really means a philosophy of building and housing. Thus, you must use low carbon materials – not only for building, but also during the production, and transport (otherwise it would be just stupid to make a house out of super-organic material brought from overseas, or have a strong insulating material but with a polluting production). In a broader sense, sustainability also concerns social resources (how to protect and develop communities), economic aspects (non-destructive growth which can be sustained on the long term, without sacrifices for future generations) and so on. Bogdan Gyemant-Selin is a convinced follower of this sustainability, beyond regulations, but also extremely concerned about what he calls the natural behavior of a building: that is exactly what traditional buildings managed naturally – to breathe, to have normal exchanges with the environment, to have healthy reactions to moisture, frost and solar heating, to grow old and then have a clean exit.

Today’s obsession with absolute thermal insulation leads, especially in the case of the famous passive house, to almost complete isolation from the outside of the interior; instead of traditional walls made of one, maximum two materials, we now have several layers of thermal and waterproofing materials that hide the construction and sometimes hinder the natural hydrothermal flows; many of them have a relatively short life span and always create joining issues (with the ground, the roof or terrace / balcony, etc.). Beyond that, it’s a little strange that in the name of sustainability and love of nature buildings are created that actually refuse contact with their environment, hermetic bubbles with complex and controlled operations that don’t allow you, for example, to open the window in winter, and smell the fresh snow.

Mono-material and anti-passive house

This criticism of standardized sustainability caused the main turning point of the project. Since concrete had become unavoidable, why not make the best of it, and actually show it extra respect and turn it into a material that could also close and insulate? Bogdan convinced his customers that it is worth to try to return to the traditional philosophy of living, but with a modern material.

It must be said that even at this point, the architect was not thinking of a complete inventory of a material. He knew that there was an experimental house made of thermal insulation concrete, developed by Bearth & Deplazes office in Switzerland, and several programs of development from large corporations (but nothing finalized). None of these technologies in progress could be brought to Romania, so the next turning point was the decision to produce a local thermal insulation concrete. Obviously, such a step went beyond an architectural solution, so Bogdan contacted Gabriela Nahoi and Aurora Capanu fromLafarge Romania (now into an aquisition process by CRH Ireland), who were immediately and enthusiastically involved in the project. Their support was not limited to counselling and delivery of materials. They have become an important player in the process; applied research led to thinking, testing, implementing and shaping an innovative product.

The result of studies and discussions and several versions of aggregates was a local, lightweight material, relatively inexpensive: basaltic slag, used inthe past as insulation material. After all sorts of combinations, transformations and tests, there came the perfect concrete with insulation capabilities that exceed those of a thick brick wall. It performs even better than the architect had imagined, expecting only a good solution to heat transfer. Experiments have shown that it has excellent water resistance, allowing complete elimination of any extra layer of waterproofing. This is a true mono-material, which can form by itself concrete foundations, floors, walls and roof. A 45 cm-thick structural frame monolithic concrete does not simply support a house, but is the house.

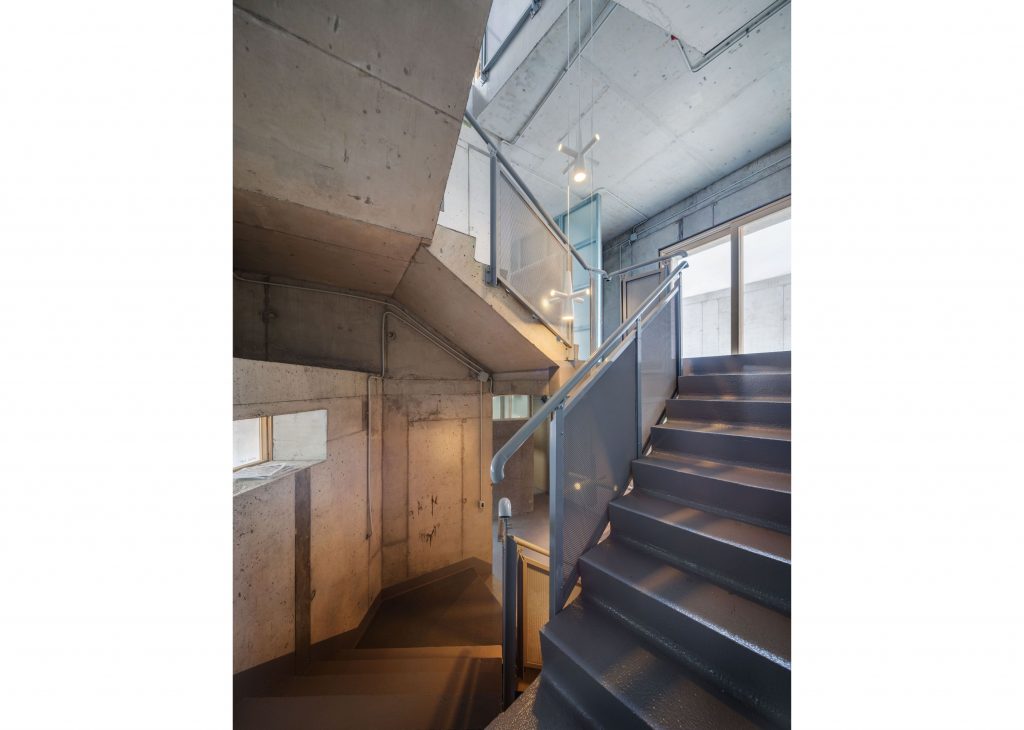

Everything about shaping and building a house today – the structure, the enclosure, the different finishes, had to be redesigned; not only mechanically, but also in terms of construction physics, in an almost scandalous way, when compared to the common construction practices. Thus, although the new concrete insulates better, energy performance of the building – C class – doesn’t do so well in ZEB terms. An efficient and economical heating brings interiors to 18°C in winter, and not to the exceeding 24°C. But here comes the comfort beyond indices. During the 2015 winter, the house has shown almost no signs of moisture, the walls were breathing and slowly adapting to temperature changes. Thermal inertia is great – the house keeps the warmth and gives the body time to adjust. In addition, underfloor heating works well exactly where it si needed – in the actual living area, close to the floor.

Another innovative device adds up – untreated poplar plywood, which integrates storage in some areas. This wooden skin gives a warm and cosy feeling to the interior, also impeding radiation from the concrete. Moreover, it was not glued on, but mounted at a distance of a few centimetres from the walls.

The layer of moving air thus created contributes significantly to air convection in the rooms and creates an air cushion that works as insulation. This was demonstrated by measurements made in 2015: there is a difference of three degrees between the inner surface of the concrete and the plywood in the room.

This plywood is a good example of a holistic concept of sustainability and architectural experimentation that did not stop with the invention of insulated concrete. All woodwork is made from untreated spruce and ventilation is achieved simply by opening the windows. The gaps between wooden parts and walls are insulated by a layer of hemp fibers. Underfloor heating is ensured by a wood stove, sculpturally exposed downstairs, like a modern fireplace.

Moreover, the smoke from burning wood (renewable fuel) is less polluting than the one produced by burning gas and the ash can be used as fertilizer; during the spring there is the advantage of a very low price for the combustible material.

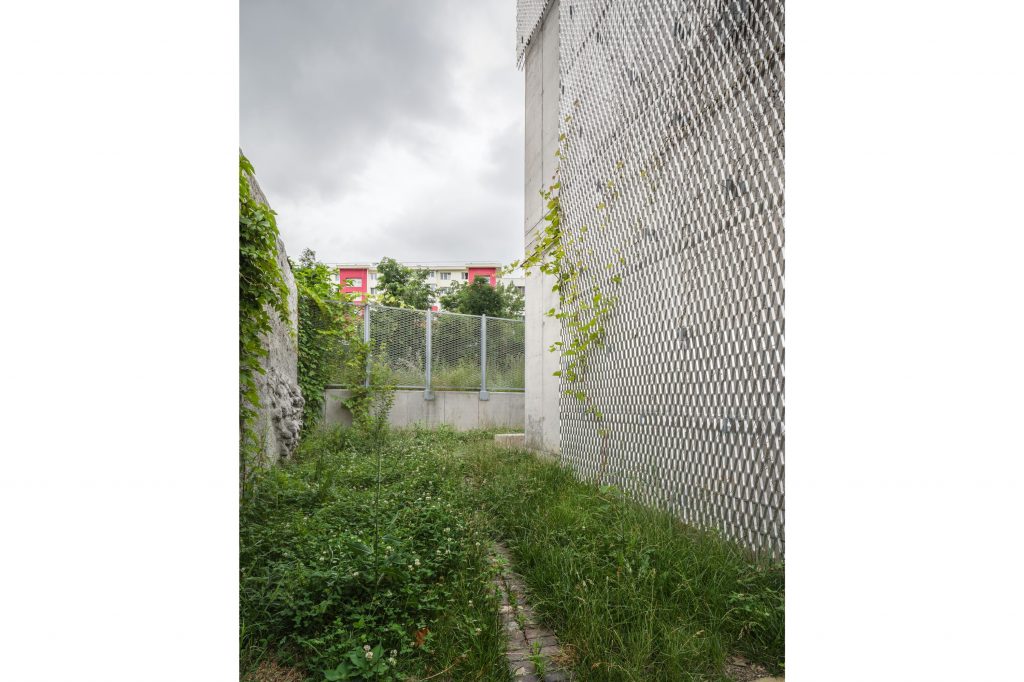

On the outside, there is an aluminium mesh (also locally produced, at a plant from the town of Slatina), which will support a living curtain of plants.

This will reduce the heating of the walls during summertime and will work together with the hanging gardens which are yet to be developed as a second roof covering the house, as compensation of the land lost with the construction.

Another experiment, that pertains not to sustainability but to the exploration of a material’s potential is the way part of the service area walls were handled.

The company was already producing a decorative concrete for floors, a highly structured surface, similar to traditional mosaic. Here, mosaic climbed the walls, the decorative concrete being applied for the first time on a vertical surface, which contrasts sharply with the smooth surface of all the other walls. In fact, it’s not a finish applied to a wall, but a merging – the treated encased concrete

becomes mosaic.

Tamed cave, shell, archetypal house, innovation

Beyond innovation, the house seems a place where you feel good. Surely, there is the architects’ weakness in front of the beauty and sincerity of the exposed raw concrete, but we think this is about more than that, and the proof is the fact that Anna Zăbavă and Mircea Toma like the result. It’s a strong and sincere construction, even austere, in which many hidden things – not only the structure but also the cables for installations, for example – are apparent. But it’s also a comfortable place, which incorporates many of the archetypal living elements. Untreated plywood and carpentry, the hearth in the middle of the house fall into this category. There are also very large glazings, which bring in generous light and the change colour and texture of the walls throughout the day and seasons.

Everywhere you are simultaneously protected and directly connected with the surrounding environment, especially garden, but also with the neighbours and the city. Even the concrete, despised by many as a sign of autistic and inhuman modernity expresses here its true nature, of liquefied and recomposed stone. The archaic coexists with a smart and complex modernity.

And finally, the metal mesh on the outside can be read as a green low-tech modern device, but also as a reinvention of the vine vaults that have been transforming for so long the courtyards of Bucharest into vegetal salons.

The concrete house is a rediscovery of natural habitation which it tries to take a step forward, through a new material. It puts Romania on the map of international innovation and has potential to the trigger here and build a new culture of collaboration beyond contracts and responses to commands. It’s a shell for the 21st century.

Credits & info

Location: 22 Institutul Medico-Militar Street, Bucharest

Architect: Bogdan Gyemant-Selin

Client:Teodora Zăbavă & Mircea Toma

Experimental concrete: Concrete product line team lead by Gabriela Nahoi, Aurora Capanu, Lafarge Romania (now into an aquisition process by CRH Ireland)

Structure: Sicon 21

Installations: DeMO Studio

Contractor: Construcţii Erbașu

Floors: SIKA

Metal works: Griro

Wood works and interior furniture: Atelier RD