Interview: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Photography in the factories: Marius Vasile

Introduction. Three discussions about design, industry, and strategies

Romania is not (yet) a good environment for design. There is no industrial commission, and design for (quite limited) series production happens in isolation – mostly in furniture, clothing, and accessories start-ups. Those who do it and manage to move beyond unique pieces, handmade, and prototypes are heroes. As a general rule, to move forward, you cannot leave the local industry out of the discussion, as well as the growth of a cultural environment and a target audience. At the same time, design today no longer just means conceiving good, beautiful, and economically efficient things, but it must question its role in an increasingly complicated, unfair, resource-depleted, and climate-crisis-ridden world. In November 2023, Bright Cityscapes, a program organized by Politehnica University Timișoara, Faber and UPT Creative Campus to initiate a design laboratory for Timișoara came to an end. I had the privilege of participating in the program by moderating the final conference and conducting three interviews with international experts: Saskia Van Stein and Joseph Grima (Eindhoven), Norbert Petrovici (Cluj). We are publishing these interviews on the Zeppelin platform. We start with the one given by Norbert – sociologist, anthropologist, working at the Babes-Bolyai University in Cluj, and coordinator of the research team of the Bright Cityscapes program. (Ștefan Ghenciulescu)

Ș.G.: I am starting all three interviews with the same question, relating to the dependence of object design on the market. From a local and historical point of view, in the former Eastern Bloc there seems to have been a huge difference between architecture (quite good and even very good, at times) and design. This seems to point out that design is inextricably linked to a market economy. Today, we have a market economy, but no real clients. What do you think about this and about chances for the development of design in countries like Romania?

N.P.: I will respond from a sociologist’s point of view, not really knowledgeable about the inner workings of design. There are parallels to be drawn between the socialist period and the present one, in Romania, at least. But, in order to understand contemporary logic, it is important to challenge the way we look at socialism.

Indeed, we don’t notice design as an important feature for goods produced in that period and sold internally or externally. And that’s because the state economy rested on two pillars. The first one is, maybe surprisingly, the exports. Since the beginning of the ‘60s, Romania strongly invested in factories whose products were aimed at the international market. The second pillar – the domestic market, was strongly oriented towards the construction sector (dwellings, factories etc.). These two types of aggregated consumption strongly dictated how the economy worked in a very important aspect: a lot of the locally manufactured products were intermediate ones; we rarely exported final products. And, if we did, they had a low added value.

There was actually a design element for the internal consumption, but the finished products were dwarfed by the domination of the construction sector. Actually, this imbalance still shapes today’s situation. Especially since the 2008 crisis, most of Romania’s revenue comes from exports, and by foreign direct investment (FDI). Even if there is a booming internal consumption, we are still essentially producing intermediate goods for international markets. Timișoara is leading in terms of engineering design, Cluj for UI and UX engineering, Bucharest for everything else. Therefore it’s quite complicated to talk about an independent design field, unlike architecture, which strives to achieve a kind of semi-autonomy from the market. The prevalence of intermediate goods for global chains doesn’t favour design.

Ș.G.: It seems that even at a global scale you’ve got a separation between companies (and countries) that own and design, and the ones that produce. The Apple slogan “Designed in California, assembled in China” seems to express this in an almost cartoonish way.

N.P.: I think the way Apple functions can tell us a lot about design. Apple is selling technology and innovation, of course, but in a field crowded with competitors. And design is one of their competitive advantages. But the company gathers around it an entire environment of firms that are responsible for parts of the products. They work at Apple with an entire network of designers, while manufacturing is completely outsourced.

Actually, many multinationals are now trying to link locally with small but technologically advanced companies. And that leads to a design environment and secondary markets. You see that happening in the Czech Republic or Poland, but not yet in Romania.

The other mechanism for the emergence of a true design ecosystem relies on the existence of a thriving local start-up sector. This start-up sector can address both the intermediate and the final consumer market. And to be able to access new markets, these small companies need design – be it UI, UX, or product design. However, in order to reach the global market, these start-ups need to re-scale. In the end, it’s difficult to imagine design on a very reduced scale.

*FLEX Timișoara © Marius Vasile

*FLEX Timișoara © Marius Vasile

Ș.G.: That’s fascinating. Beyond design, what you say also shows that, even with all the globalisation, instant communication and everything else, the place, the region, the local networks are still essential. Your work with people from Timișoara, because you know them, maybe you studied together, it makes everything easier and safer.

N.P.: Exactly. The networks in Timișoara work extremely well. The city has some huge advantages: a strong engineering tradition, developed in the last 150 years, including the socialist era; right now, in terms of engineering, it’s the leading Romanian city. But the point now really is how to create an independent sector that would be capable of innovation, relying on the same network. The high-tech and mid-tech companies there could become a market for this innovation.

The multinationals are indeed trying to create such a system, but they are still captive in their own way of functioning. Most of these multinationals include intrapreneurship in their activity: they are paying their employees to bring new ideas to the table, and if these ideas prove valuable, they start new companies or file patents. But then, these patents are registered in the home country of the firm. For a local spillover of work or projects from these companies you need a total re-arrangement, to help reduce the cost of the transactions, in order to create the environment we are talking about. This is complicated.

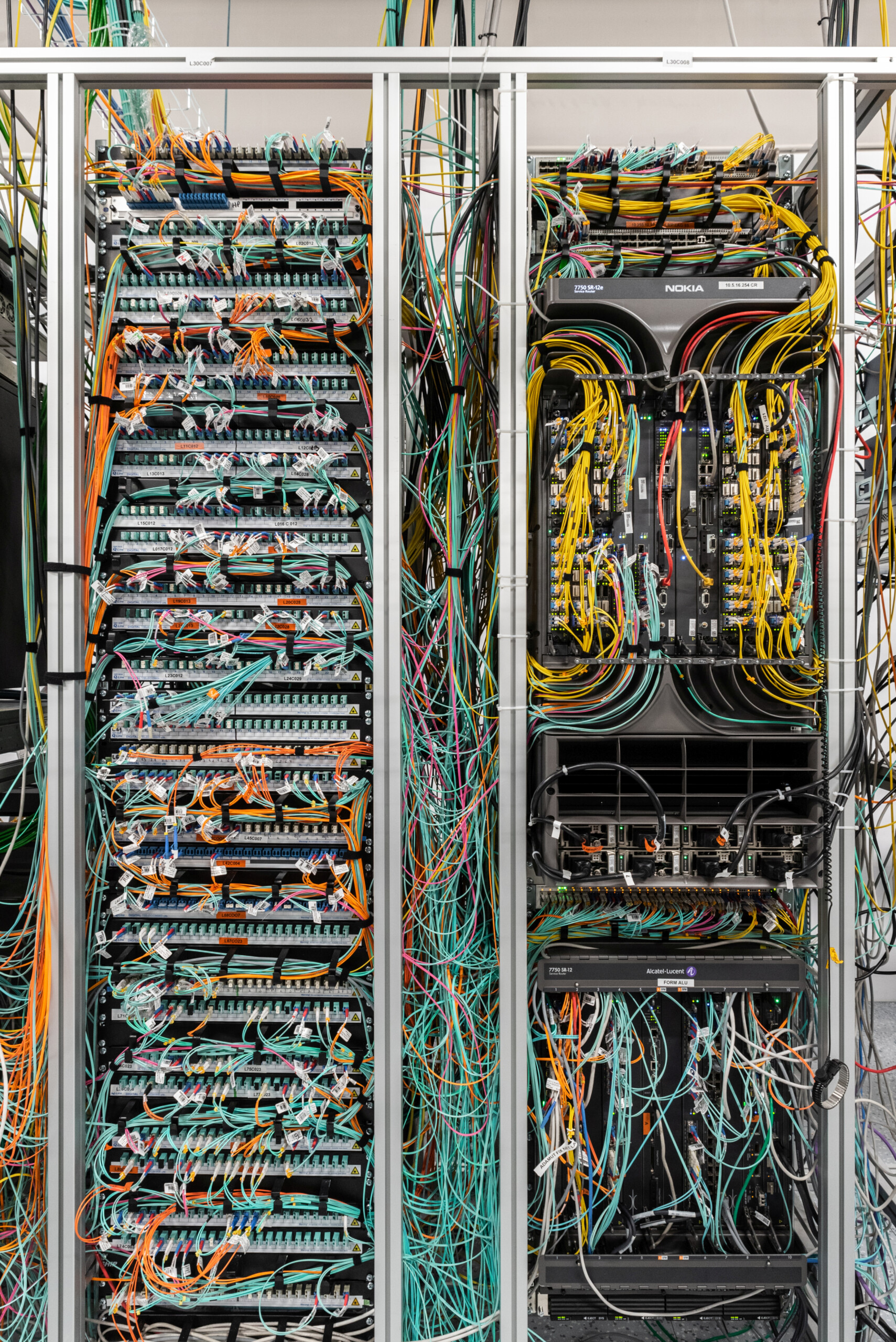

*NOKIA Timișoara © Marius Vasile

*NOKIA Timișoara © Marius Vasile

Ș.G.: The relatively strong design environment in Poland and the Czech Republic is, of course, strongly indebted to those countries’ technological and industrial history. But design is also the subject of national policies. The state and the local communities support teaching, fairs, start-ups etc.

N.P.: Yes. Like the Romanian state supporting the IT sector through tax cuts and other measures, you need strong central and local strategic support.

Ș.G.: Let’s discuss the city a bit in spatial terms, even if that will maybe lead us away from design. In my opinion, the decent legacy of the ancient regime is social urban mixing. Even with gentrification going on, you still find lower-income people living in the centre of the city, large neighbourhoods with very different types of dwellers – things that are a thing of the past in the world’s large and successful cities. Is this in any way linked to a specific industrial landscape? And is there a chance for this mix to survive?

N.P.: I have been questioning this, for instance in a research that was focusing not on industry, but on schools. The quite large amount of capital entering Timișoara compared to other big Romanian cities is actually not so visible in the city itself. That is because most of this investment went into peripheral areas – mainly, the second and third city ring. Like Bucharest, even if on a smaller scale, Timișoara has been and is sprawling. The peripheries display different characters, though: Dumbrăvița houses the managerial class, while in the south, there gather the middle-class start-ups. Territories become specialised.

The centre was less sought-after; it remains rather untouched, and even with areas of decay juxtaposed to ones with intensive investments, like the Iulius private neighbourhood.

In Romania we now witness a booming housing development, particularly in former industrial areas – large chunks of free space within the city. My problem is that these terrains are usually refurbished by a single owner and quite strictly dedicated to the middle-class. Gentrification is indeed inevitable, unless new types of housing development also emerge. Near Cluj the „model-neighbourhood” of Sopor is being developed (and indeed in the north of Timișoara they would like to follow this model). There was a planning and architecture competition for it, and the results are quite good and beautiful. But then the city is actually not able – legally – to impose this development plan on the more than 800 private land owners. So it seems that the Zoning Plan for the area is going to become an annex of the General Urban Plan for Cluj, and, in order to build, each of the owners will be obliged to deliver their own small Zoning Plan, also integrated into this annex. Which is complete nonsense.

The Socialist planning laws, which completely disregarded private property, were cancelled, but good new laws that would enable the public administration to regulate the development on private property and to create areas for collective housing, for instance, are not in place.

Actually, only in Bucharest and in a few other cities there is this problem of wild densification, including in precious urban areas. Nationally, cities undergo the opposite process – they are shrinking. Bucharest is so significant and visible a city, and the transformations are so brutal, that the urban laws are meant to keep this wild development under control and to reduce land grabbing and corruption. But then they do paralyse the other cities, including Timișoara. About 2,000,000 people live in Bucharest and another 2,000,000 under independent administrations just outside the city, while being totally dependent on it. Well, for Cluj, this number is about 50,000. There should be an acknowledgement of this different type of development logic.

If the laws won’t change, nothing will stop gentrification and sprawl.

Ș.G.: No more questions. But I will let you bring up any important topic I missed, or define a conclusion for this interview.

N.P.: I think that right now we’re getting a huge opportunity to change our way of thinking about the built environment. Romania will have to produce nearly (and then soon) net zero energy buildings. The European Bank for Regional Development will finance 85 % of this change and there will probably emerge new municipal bond markets. This concerns the major part of our building stock – existing or to be created. The construction and financing paradigm will be completely different, and, to be honest, I don’t know how this is going to work.

Now, the construction and the export markets work within quite different systems – different interest rates, for instance. For designers and architects, the green revolution will mean a new field of action, as the old buildings stock, including the huge mass of socialist buildings, will have to be refurbished. Product design, on the other hand, will need the strong start-up sector and the public policies that we were discussing earlier. Still, overall, I think we have a duty to be optimistic about this wave of change.

* About the lab: https://brightcityscapes.eu/en