From most of the photographs circulated on the Internet, especially at a cursory glance, the Plasencia auditorium appears to have been randomly thrown into a field, in an absurdly peripheral position, yet another of those many self-sufficient objects, planted in the middle of nowhere by egotistic local administrations and architects.

It is certainly not the case. What might seem at first an act of power is in reality a gesture of tenderness.

Project: Selgascano

Text: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Photo credit: Laurian Ghinițoiu

The site

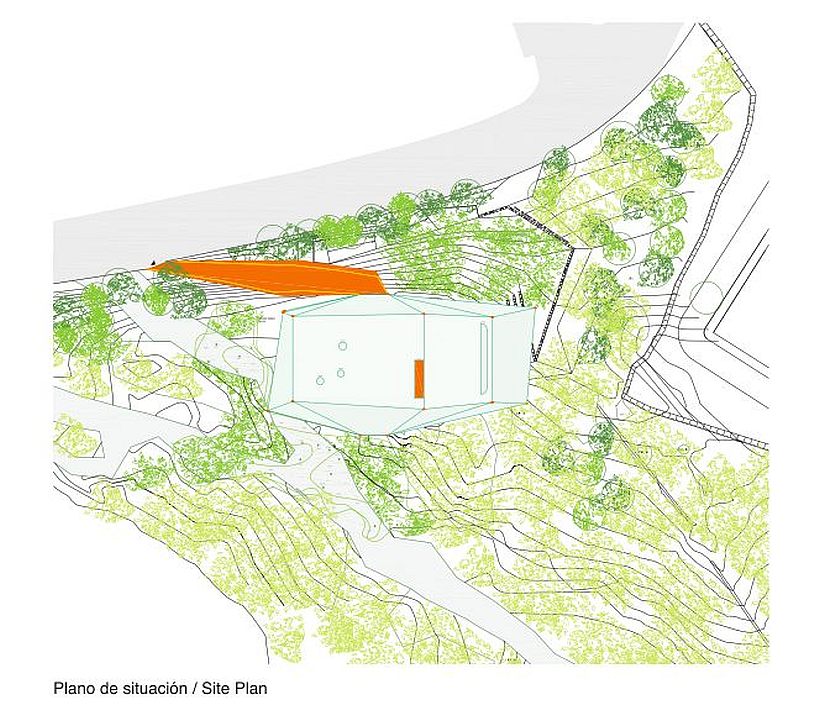

The building does not sit outside the city boundary but on top of it, between the natural landscape (with its harsh beauty typical of the Extremadura region) and the newest residential neighborhoods of a small but old and proud city that looks forward to growing. Between the two worlds stretches the highway; on the “natural” side of that highway, the site of the Center.

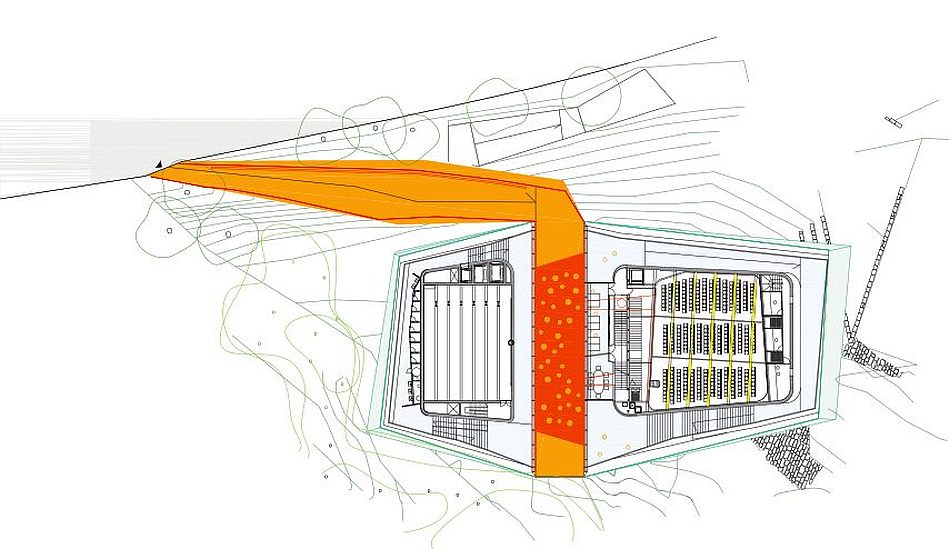

While located inside the natural landscape, the building clearly belongs to the city. It is obliged to work as an urban extension. selgascano opted for ensuring that their intervention belongs to the natural setting as much as possible, barely touching the original landscape, namely a steep slope that starts right behind the highway, and for keeping it as separate as possible from the level and logic of the city.

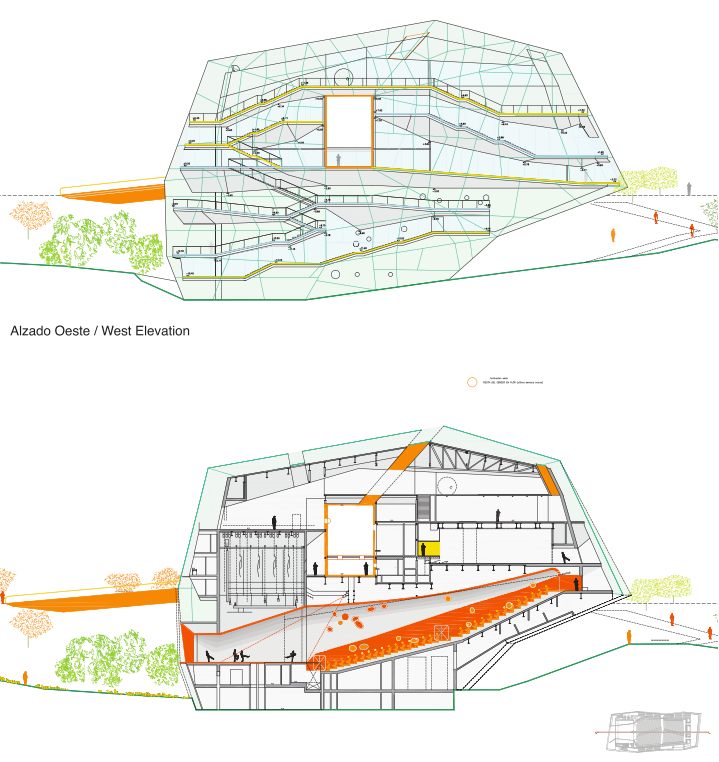

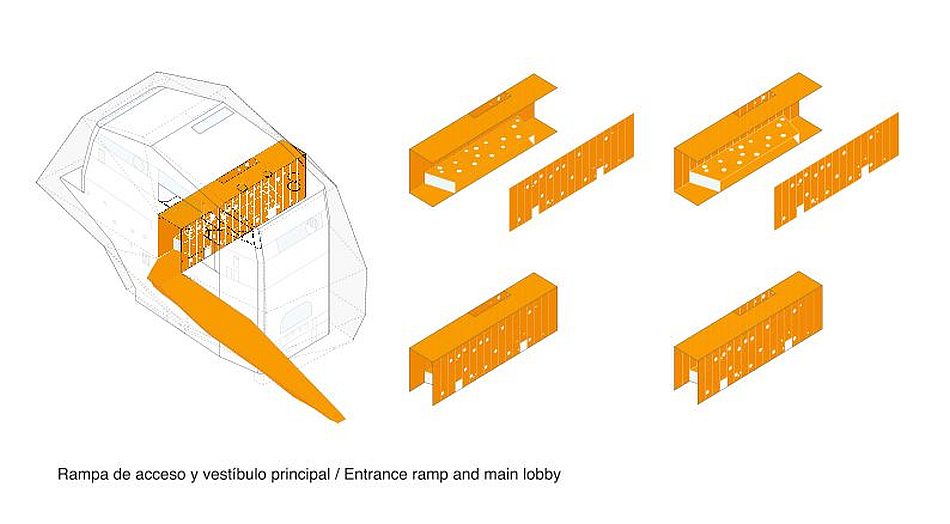

Hence the solution of isolation and extreme concentration: only the smallest part of the building is rooted in the ground, and from there it grows without ever touching the natural terrain again. The link with the city is created in the most delicate way, through a gangway that starts from the street level and reaches 12 meters above the ground-floor. Cantilevered off the ground, the concentrated object thus keeps the field clear and marks an ending of the city at the same time. It works as a boundary marker: this is how far we are supposed to grow.

You can get the information above from the authors’ presentation. And I admit that only when I got there, as a member of the jury of EU Mies Awards 2019, I understood the radicalness and the necessity of the gesture. The natural setting in the middle of which Plasencia sits is made up of hills and valleys. Indeed, the old city was built accordingly; it adapted to the natural contours. The new residential complexes however went for the apparently easy solution, in fact as much irrational as it is aggressive since it means sitting conventional slabs and terraces on an embankment with retainer walls as high as 15 meters. This covers up not only the open space but the contours of the landscape itself, in an accelerated move to make everything flat that ruins the character of the place.

Under these circumstances, selgascano’s option points to a different development model — more concentrated and with a smaller built-up surface area. If, in the worst-case scenario, it will remain an exception, it will nevertheless succeed in preserving a significant portion of the land, an island of natural landscape in the middle of an expansive landscape swallowed up by the city.

Core, skin. The Archigram dream

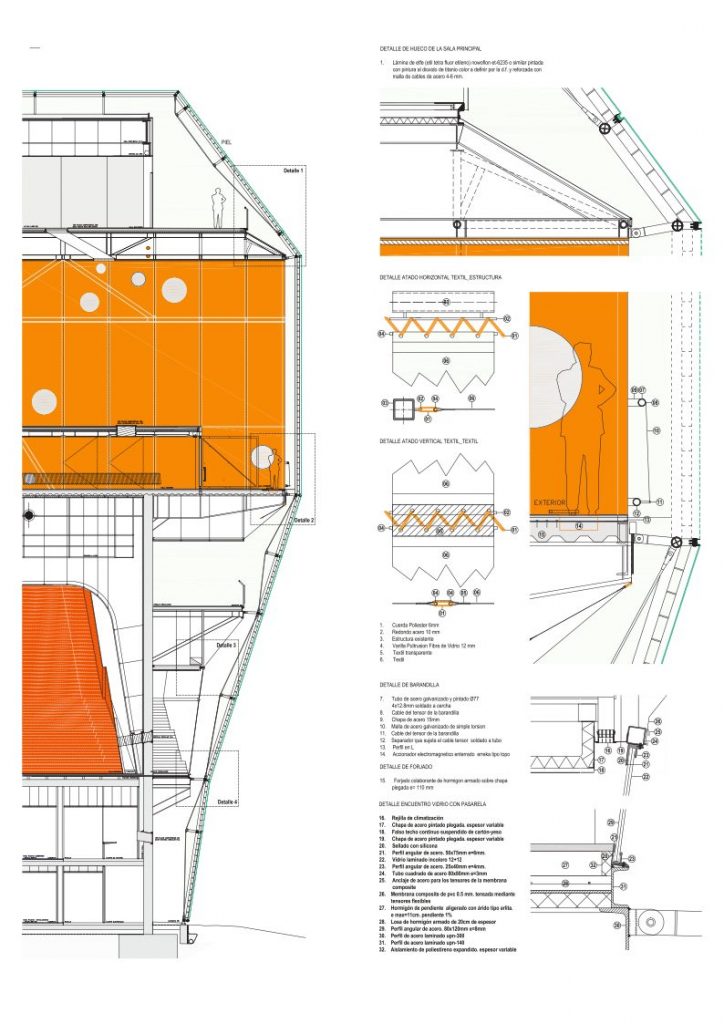

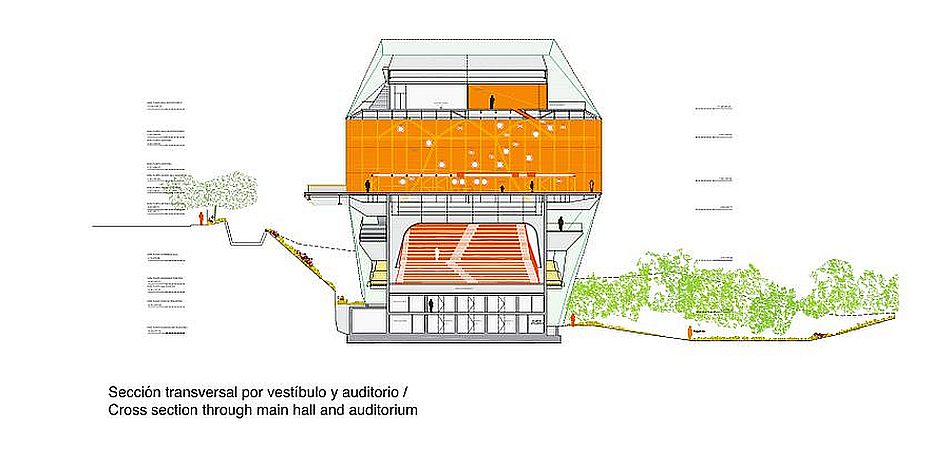

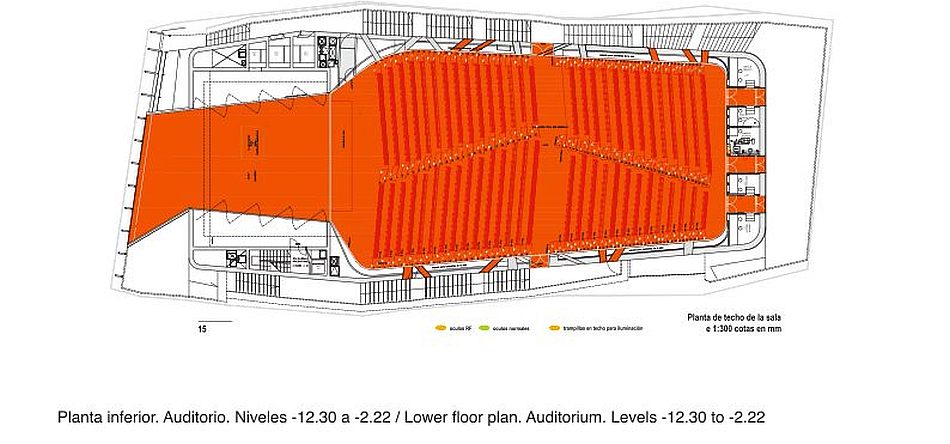

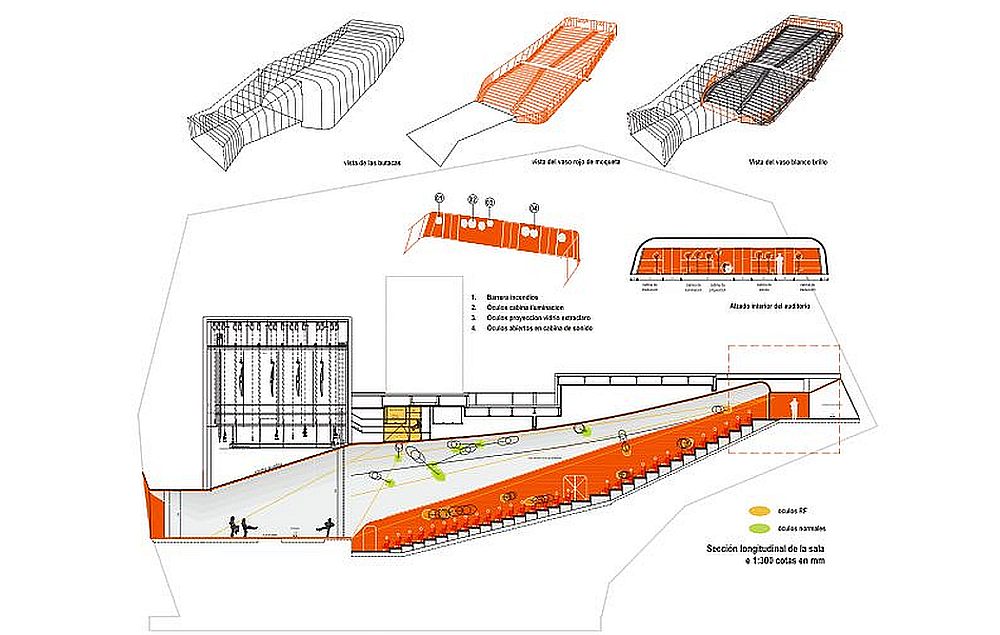

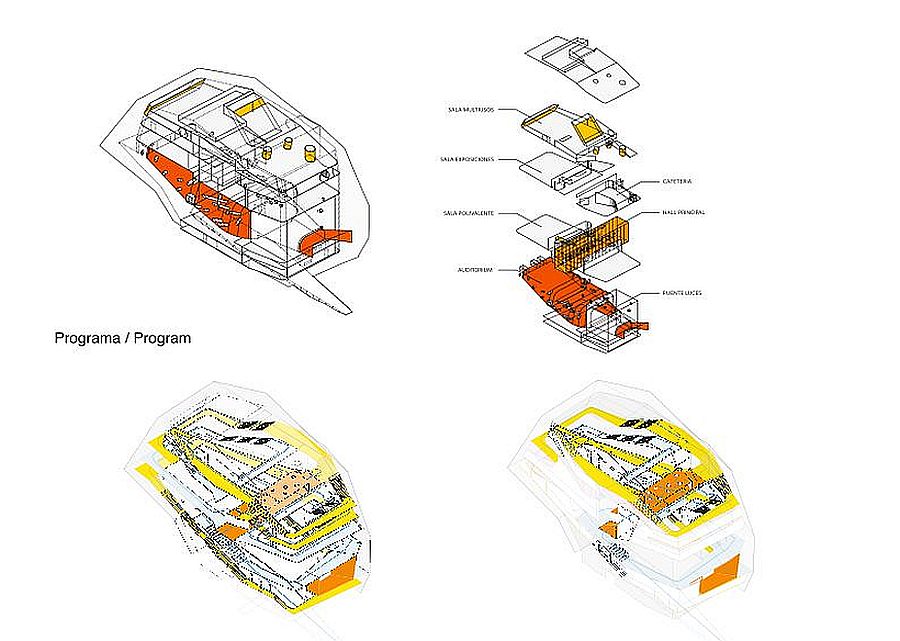

The logic of the building is concentration, which means that the building grows on the vertical. A strong concrete core structure thrusts into the ground sustaining. It houses the auditoria, the conference rooms and all the services, along with the entry portal, shaped as an extension of the gangway entry and forming a tunnel of light and air that passes through the building. The circulation routes and most of the other public areas make up an architectural promenade inside a metal structure attached to the concrete shell and sheathed in two skins: one made of glass, partial and discontinuous, and the other, a translucent and permeable skin that covers almost the entire building. The translucent skin keeps off about 50 percent of the solar radiation, achieving the difficult balance between solar control and transparency.

The stable, strong core, which holds the auditorium seating works very well with the soap bubble enveloping the building. From the outside, during the day, the non-orthogonal volume and the light and translucent boundary make a minimal impact on the natural setting. In the evening and at night, the building turns into an oversized lantern and a beacon that signals the beginning of the uninhabited landscape and the urban “shore.”

Architecture is born here out of the fragile equilibrium between opposite values: roughness and softness, opacity and transparency, and from the seemingly impossibly but surprisingly well working match between contrasting, vivid colors (selgascano’s trademark). But it also grows out of unexpected connections such as the circular perforations that create lines of light and visual connections between various spaces or views from the opaque or translucent interior towards the landscape.

Walking around this building, you cannot help thinking of Pop Art and feeling literally submerged in a Yellow Submarine universe. Personally, as early as the Jury’s first selection, but even more so during the actual visit, the architectural reference I was most reminded of eas the world of Archigram: the smart and lyrical megastructure, the passion for technology and the unadulterated pleasure for doing architecture, the mix of optimism and humor (in stark contrast with hard line classical modernism); in short, the Archigram visions brought to life the moment technology is advanced enough to support them. Both the scale and the architectural definition seem to stand between Reyner Banham’s and François Dallegret’s 1965 “un-house”* and the much more famous Ron Heron’s 1964 “Walking City.” I just hope that the selgascano building won’t turn loose and leave Plasencia.

* [Un-house. Transportable standard-of-living package, architectural drawing by François Dallegret to illustrate Reyner Banham’s article “A Home Is Not a House,” Art in America, Issue 2, April 1965.]

UFO and heroic bricolage

In terms of construction, this project was one of the biggest surprises of the architectural tour. I have never seen such a mix of technology and state-of-the-art architectural details, on the one hand, and extremely low-budget solutions, executed by the local workforce, on the other.

Extremadura has a history of economic problems, which made it difficult to finance ambitious operations from the outset. But the real obstacle was the financial crisis, which hit at the height of the construction works. Hence the significant discontinuities—the project started in 2005 to be finished only 2017—and the need to make do on a very low budget.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the architects’ dedication and their good relationship with the local administration saved the project. The building is full of solutions developed during the construction site stage (which was closely supervised), tricks to save money, and smart details. Adaptation was a wise strategy, and it could be a lesson for countries like Romania. Instead of uniformly setting back costs on all the aspects of the project, and thus inevitably ruining the solution, selgascano went for the extremes: zero compromise on the main sections and cuts as drastic as possible for the rest. The budget cuts are visible but I didn’t see any structural or waterproofing issues, or any signs of accelerated wear and tear as with many famous buildings that look impeccably on opening and terrible a few years on.

This decision saved the complex metal structure and the outer skin. They managed to have the latter installed before the construction site was temporarily closed on account of the crisis and, ten years on, I can safely say that it was in mint condition; for the remaining details, they ran a very tight ship and made do with whatever was available. The painting is therefore a good average one; with the exception of one (expensive designer) lamp, the lighting is the cheapest available. The quality of the execution is rather unequal: for the outside circulation routes, the concrete surface was stamped with profiled sheets commonly used for water insulation: the negative pattern effect is beautiful—but the actual construction is hit and miss. Sometimes, however, the thriftiness approach delivered good results: since they could not afford to cover the entire volume in glass, there are common areas which are now located both inside and outside, adding complexity to the architecture and functioning rather well in the hot and dry local climate. Maybe my Balkans background is to blame, but I confess I was rather moved by the general mix of high-tech and “makeshift” solutions. The painted reed wall that had nothing to do with the spaceship volume, the bench made of ordinary pipes, leftovers from the construction site, and the rebar railings for the gangway, they all touched me. Equally touching was the constant effort to recycle as illustrated by the worn outdoor carpeting of the gangway turned wall finish in the exhibition room.

*Fireowrks and a collision of scales nd materials, power and gentleness, Hi-Tech and humble materials; foto: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

*The poetic insertion and the preservation of the landscape are visile even from under the overhang auditorium – it’s a place that could easily become an open-air and shaded auditorium; photo: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

In lieu of conclusion, I want to say a few words about the people. On our tour, we were accompanied by the manager of the center and an important local politician, both of them very proud of the building, and also by a gentleman, who kept himself somewhat aloof. It turned out that he was an expert in administration, who had just retired after a life of fighting for quality architecture and for awarding regional public projects through competitions. We owe to him both the competition for this project and the one won by Rafael Moneo who went on to build the Mérida museum. José Selgas and Lucía Cano introduced him to us with great respect, mentioning him in all the conversations and speeches about the project, including at the wards ceremony. He is the kind of person that architects and the civil society should look out for and win over to their side.

Info & credits

Finalist project at EU Mies Awards 2019

Name: Auditorium and Congress Centre, Plasencia, Spain

Period: 2005-2017

Authors: selgascano – José Selgas (1965 Spain); Lucía Cano (1965 Spain)

Collaborators: José de Villar, Carlos Chacón, Julio Cano, Lara Resco, Lorena del Río, Manuel Cifuentes, Beatriz Quintana, Jeongwoo Choi, Laura Culiañez, Bárbara Bardin, Johannes Riekert

Architectural Assistant: Manuel Trenado

Façades: Fhecor ingenieros consultores

Mechanical: JG Ingenieros

Acoustical: Arau Acústica

Textil Architectures: Lastra Zorrilla

Constructor: Placonsa-Joca

Total built area : 20. 000 m2

Client: Junta de Extremadura