A pro-bono project of the prestigious Swedish architecture and design office Claesson Koivisto Rune

Text: Daniel Tudor Munteanu

Photo: Alik Usik

Context: reform, decentralization, a new kind of rural public building

Novi Sanzhary was an urban-type settlement with about 8,000 inhabitants, located in the central-eastern part of Ukraine. Why “was”? Because now it’s a hromada. Let me explain.

Urban-type settlements are those little towns from the ex-Soviet space, slightly more important than a selo (village) or a selișce (larger village) and yet smaller than a city of raion significance. Until two years ago, these types of settlements constituted the third level of Ukrainian administrative division, having as higher levels the raion (district) and the oblast (region). In July 2020, the Parliament approved the administrative reform to merge most of the existing districts and to consolidate the small third-tier settlements into united territorial communities called hromadas. In a major decentralization effort, the new hromadas took over most of the district’s administrative tasks: capable communities have been granted with broader authorities, resources, and responsibility. The list of public services that can be provided at the level of a hromada is constantly expanding and may include population register services, social assistance, construction issues, land issues, real estate registration, registration of business entities, Passport and ID card services, etc.

The hromadas seem to be somehow similar to the communes in Romania. Only that Ukraine, with a territory three times larger and having 30 million inhabitants more than Romania, is now divided into only 1469 hromadas. About five times less than the communes in Romania, if we were to make a proportional calculation.

Administrative reform and decentralization have been doubled by consistent efforts to debureaucratize and digitize the administration. According to the official reports, public administration databases are in the process of becoming fully interoperable, so that the citizens have to provide diverse data only once. The interaction and secure data exchange between state registers and information systems is ensured by the Trembita data exchange system (developed on the same X-Road digital infrastructure that supports Estonia’s e-governance platform, but using Ukrainian cryptography). The Diia mobile app and the e-government portal of the same name take inputs from citizens, handle payments and store the official digital wallets, while the Vulyk information system automates the services offered by the administrations. “Making data run, not people” – the slogan that accompanies the media campaign of the Ministry of Digital Transformation forecasts the disappearance of the much hated fastener file folder.

Ukraine is the first country in the world where digital ID cards and driver’s licenses have the same legal status as their physical counterparts. Today, for example, Ukrainians are allowed to cross the border into Moldova and Poland only by showing their digital e-passport.

The accelerated digitization and automation are not only a formidable weapon against bureaucracy and corruption in the public sector, but are part of the national defense strategy. Not only do they lead to increased public confidence in the state, but ensure at the same time the digital continuity of the state in case of foreign invasion, civil war or natural disasters. Ukraine has committed to migrating online one hundred percent of public services by 2024. Following the Estonian model, its next priority would be to set up “digital embassies” that host on foreign territories complete encrypted backups of state registers: from the system of information of the treasury to the land cadastral register and from the State Monitor to the population and business register. A resilient state, with a central and local administration that can function, without interruption, in the cloud, is difficult or even impossible to defeat.

Despite conducting real reforms in recent years, Ukraine remains a state with systemic corruption at all levels of society. According to last year’s Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, Ukraine ranked 122nd out of 180 countries and is vying with the Russian Federation for the title of the most corrupt country in Europe. In the same ranking, Romania occupies a much higher position than Ukraine, although it is on a not at all honorable place 66. The first positions are occupied, not surprisingly, by the Nordic states – Sweden, Finland, Norway and Denmark stand out as the world’s most incorruptible nations and, as such, are acknowledged providers of good practice in the fight against corruption.

Returning now to the Ukrainian hromadas, the newly established administrative structures have been faced with the problem of the lack of a suitable physical interface for their interaction with citizens. The old administrative buildings, in the communities where such facilities do exist, are associated in the collective mind with systemic corruption and endemic inefficiency. Public trust is nourished equally by symbols and by direct experiences. And the digital experience is not enough – at present, the Internet penetration rate among the Ukrainian population is considered to be between 70-80%, which means that almost a fifth of the country’s population, especially in rural areas, has never used the Internet. It is a rather worrying figure for a government that relies so much on digitalization, but not as worrying as the percentages of 40% of the population with substandard digital skills or 15% of citizens with total digital illiteracy. A sign that, at least in the poor rural areas, inhabited mainly by the elderly, the classic direct contact with the administration remains for now unavoidable.

Precisely in order to mediate the direct contact between the citizen and the state, the Ukrainian state accompanied the decentralization reform with the establishment of centers for administrative services (ASCs). These are key facilities in which residents meet their local authority and are somehow similar to the Romanian communal town halls. The establishment of ASCs in all 1469 hromadas by 2024 is a mission carried out through the U-LEAD with Europe program, funded by the EU and its member states Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Poland, Slovenia and Sweden. The U-LEAD with Europe program aims not only to finance and monitor the implementation of ASCs, but also to use the European know-how in order to increase the quality of services provided by the public administration. Core European values such as competence, efficiency and integrity are instilled in the new Ukrainian civil servants through intensive training programs, while specially designed guides and procedure manuals detail the interaction between the citizens and an inclusive, friendly and, most importantly, trustworthy public administration. According to the description of U-LEAD with Europe, the ASCs must become a ‘one-stop-shop’ for public services, but also a meeting place with local authorities and other residents to discuss solutions for the development of the hromada. The administrative service centers must be public spaces without physical and psychological barriers, where absolutely everyone feels welcome.

Type-project, model project

Refurbishing and adapting existing buildings for the establishment of ASCs is, of course, the first recommendation of U-LEAD experts. At the same time, where existing buildings are difficult to bring to the required standards of accessibility and energy efficiency, the construction of new buildings is encouraged. U-LEAD has made available to the Ukrainian government a set of standardized, replicable projects for energy-efficient administrative service centers, specifically designed to be built with local materials, technologies and workforce. U-LEAD has also completed the construction of four such pilot projects through a joint program with the Swedish government development agency Sida (The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) and SALAR / SKL International (The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions).

For the design of such a pilot project, intended to be built in the Novi Sanzhary hromada, SKL contacted in 2020 the prestigious Swedish architecture and design office Claesson Koivisto Rune. Founded in 1995 by three young graduates of the Stockholm University of Art, the office run by Mårten Claesson, Eero Koivisto and Ola Rune soon became a leading exponent of contemporary Swedish design. Their work spans from furniture, jewelry and cement tiles to public and private buildings in Scandinavia, Japan, China or the USA. Claesson Koivisto Rune were the first Swedish architectural office to be invited to exhibit at the international section of the Venice Biennale and their architectural style was praised by Paola Antonelli, the lead curator of MoMA’s design department, as “the epitome of the aesthetics of the new millennium”.

Claesson Koivisto Rune has designed pro bono a standardized project for a center for administrative services, considering that each of us has at some point the duty to provide free services in support of a noble cause.

*Model [The complete project is available for free consultation here. A backup version has been archived here]

The ASC in Novi Sanzhary seems to me to be one of their best projects.

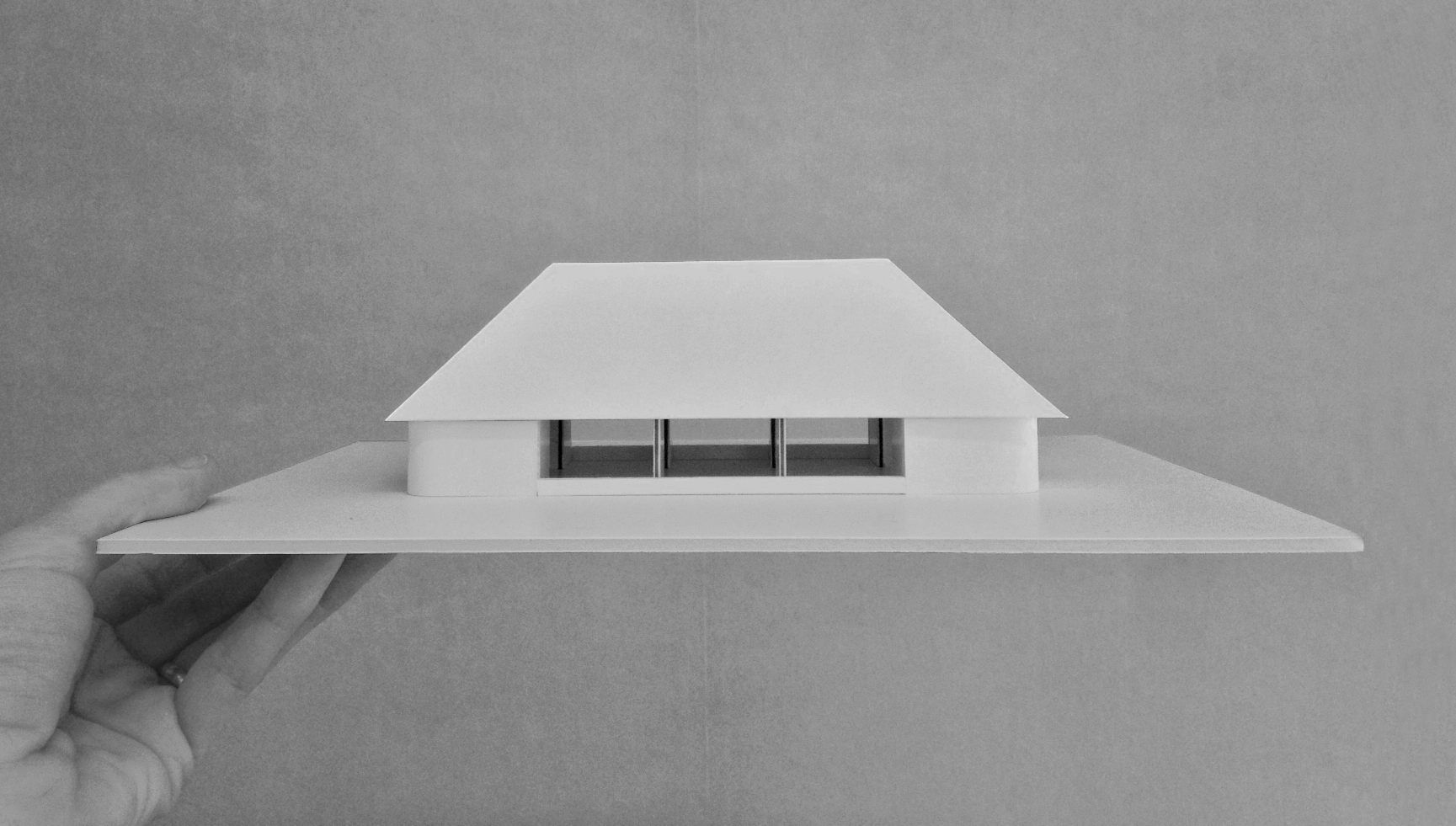

Similar to their Örsta Gallery (2010), the administrative center project shares the same pursuit of infusing public buildings with a dignified, somehow timeless character. Quoting from the authors’ description: “it’s a bit unclear if it’s built today, yesterday, or tomorrow.” Indeed, a detached passer-by might not even notice something really special in the building’s architecture. Seen in context, the building completed in 2022 seems to be “born there”, even if the feeling of familiarity might hide something strange.

The authors could not visit the building neither when finished, nor during construction. The travel restrictions imposed by the state of emergency associated with the pandemic have made it almost impossible to travel from Stockholm to Novi Sanzhary.

With the construction site being monitored only through online Zoom meetings, the fact that the architects declare to be fully satisfied with the end result may seem a bit surprising. Especially in the conditions of the scarce budget and with the Ukrainian builders not necessarily being famous as masters of precision (at least compared to the Scandinavian standards). But, in fact, it’s nothing surprising. The building was designed from the very beginning so that it could cope with imperfect details or with last-minute changes of materials (initially the building was supposed to be clad in red brick, with the roof in a matching color). For a project intended to be replicated dozens or maybe even hundreds of times, it is important that the major compositional gestures ensure enough conceptual resilience to cope with the inherent (and innocent) local deviations.

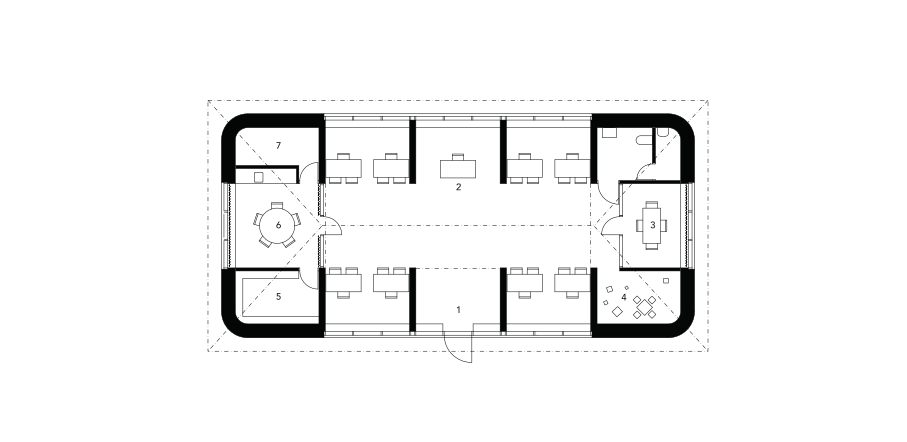

The project stands firm precisely because of the somehow archaic simplicity of its composition. A rounded parallelepiped plinth is crowned with a high hipped roof with steeply pitched slopes. The two axes of symmetry, encouraged by generous parietal glazing, are framed by solid vertical planes that give stability to the volume. The result is monumental, but not imposing. Abstract, but familiar. Neither a temple, nor a house, although it borrows much from both. The inspiration from the local vernacular is more than obvious but the architects managed to avoid slipping into pastiche. The inner space is not composed by addition, but through division. The uninterrupted interior is divided into equal bays, forming apses on either side of the central nave, progressing in enfilade along the entire length of the building.

*Plan: 1. Entrance. 2. Reception.3. Meeting room. 4. Kids corner. 5. Archive. 6. Staff room. 7. Technical room

I was mentioning before the importance of symbols in supporting or undermining the trust in authority. The symbolic reading of the project gives an account of the elegance with which Claesson Koivisto Rune built with strictly architectural means a fragment of a more just society. Architecture is here a clearly political act. The clarity of the symmetrical composition, reinforced by the building materials’ monochrome palette, infuses the building with a sought-after monumentality. Without being oppressive, this monumentality radiates a certain kind of trustworthiness. At the same time, the solidity and severity of the volume give it a dignified, determined posture. Deference is won, not imposed. The strongest impression is that of steadiness, stability and utmost honesty.

The building resembles a Foucauldian device that “rationally and concertedly manipulates power relations, intervening in these relations of force to orient them in a certain direction – either to block them or to stabilize them.” [Michel Foucault, “Dits et Écrits 1954-1988. Vol. III (1976-1979)”, Paris: Gallimard, 2004]

However, the usual balance of power between the citizen and the state bureaucrat is reversed. As in an overturned panopticon, the supervised and the supervisor change roles: the bureaucrat is now the one exposed to the “unseen public eye.” The workstations of the civil servants are intentionally placed in pairs, two by two and facing each other, being completely exposed both to the inside and to the outside observer. The open-space flat organization eliminates the classic institutional hierarchy and leaves no room for niches and corridors for possible illicit “negotiations”.

The same principle applies to the outdoor spaces: the rounded corners of the building seem to take literally the expression “no hiding around the corner”, turning it into a unique architectural feature. The architecture of the building functions as a perfect device capable of “controlling, directing and strategically containing the conduct of the subjects.” [Michel Foucault, “Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison”, Paris: Gallimard, 1975] Not only now, but also in the future: the volumetric rigidity establishes a firm outer perimeter that, doubled by the rigorous organization of the inner spaces, does not allow room to grow to the bureaucratic apparatus.

It remains to be seen if and how this pilot project will be replicated in the future. Just inaugurated, it is too early to know if the architectural and management hypotheses have produced the expected results. The premise exists, but the future is always difficult to anticipate. It also remains to be seen whether the administrative reforms of digitalization and decentralization will continue at the same pace. For the time being, the enemies of democracy and of European values have a very different opinion.

I am writing this text on the twenty-ninth day of the war. So far I have deliberately avoided making any reference to the invasion of Ukraine and to the horrors that are happening across the border. But this ongoing war cannot be ignored. For now, Novi Sanzhary appears to still be outside of the conflict zone. However, the nearest front line is only 150 km away, where the town of Okhtyrka is bombed just as I write these words.

However, I hope that when you read these lines, the war will be over and the troops of the Russian Federation will have withdrawn completely from the sovereign territory of Ukraine. I can only remain optimistic and maintain my strong confidence in the resilience of democratic values.

Slava Ukraini! Русский военный корабль, иди на хуй!

Info & credits

Financing: Sida

Title: Resilience. ASC Center for Administrative Services in Novi Sanzhary, Ukraine.

Architecture: Claesson Koivisto Rune Architects

Key personnel:

Alexander Mazurkin, Project Manager, SKL International, Stockholm

Olga Glazunova, U-LEAD Team Leader Ukraine