Níall McLaughlin received the Royal Gold Medal this year, following the unanimous vote of the RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) jury. It does not surprise us. With over 30 years of practice, McLaughlin not only designs by closely following his principles, but also teaches successive generations of students a different way of doing architecture.

We met him at *FAST (Festival for Architecture Schools of Tomorrow) and learned that, in his teaching career, he positions himself more as a mentor than a master. To paraphrase: “Telling me what to do bores me a little. I really like to find out what other people want and how they think. And if I can, to help them reach the end of their own ideas.”

In Zeppelin 175 we dedicated a DOSSIER to him, preceded by an interview conducted by Cătălina Frâncu, which we are now publishing online:

*Balliol College Master’s Field Development

*Balliol College Master’s Field Development

INTRO

Reporter: Cătălina Frâncu

Photo: Nick Kane, NMLA, David Valinsky, Níall McLaughlin

I first met Níall McLaughlin at the FAST Festival of Schools of Architecture. I was struck by the way he spoke about architectural education and his propensity to always be found surrounded by a group of students to whom he listened with overt interest. With great curiosity he asked them about their diploma work, teaching methods, the hardships and joys of being architecture students. The warmth he conveyed made students seek him out even during parties, much to everyone’s amusement.

We asked him about his early career as an architect and his favorite teaching methods, and he responded with enthusiasm and great understanding for the changes each generation goes through.

The interview, together with three projects geared towards the physical and mental well-being of students, indicate the professional priorities of Níall and his team while revealing the pedagogical profile of one of the most liked teachers of the discipline.

Beyond practice and teaching, Níall McLaughlin Architects is concerned with themes such as caring for the elderly, engaging with their lives and the state of students in a climate that isolates rather than brings together. The projects are designed, then, to encourage interaction, enhance relationships between residents and make room for chance.

The conversation with Níall took place at FAST (Festival for Architecture Schools of Tomorrow), where we were able to spend a few days with invited guests, students and architecture schools.

Construction, learning as professional practice, and the curiosity sparked by the minds of others.

Cătălina Frâncu (CF): Given the space that your teaching practice takes up in your professional life, I would like to ask you what changes have you observed in the teaching processes since your student years?

Níall McLaughlin (NM): When I started to practice I was maybe 26-27, and I was in London, but I wasn’t from London. I didn’t actually know that many architects there. So I started teaching and I started building small-scale. I had two groups of people who I worked with: makers and students. They were my people so to speak. I was working by myself from my own front room. So my images of the world and my conversations were informed by makers. I’ve always tried to keep that sense going in my work. I don’t think of teaching as a form of giving. I’m going out to teach because I want something, I’m looking for something to fortify my creative practice by teaching. So it’s very much an exchange of things happening on both sides. For me that’s the central part. As soon as I’m not doing that, I’m preaching, not teaching.

When I have ideas that I’m thinking over for a longer time, things that are not easy to integrate directly into practice, it is possible for me to put them into the teaching environment as themes we could work through for a number of years to see what their possibilities are. When the possibilities emerge, it becomes easier to integrate them into practice.

I think I was talking about it to some students earlier, you forget the professional aspect of it. You become an architect on the first day of the first year and you begin to practice. You can’t spend years to prepare to become an architect. You can speak to the city through projects that you do. And when you finish, you begin your professional practice, and you continue learning. You have to continue learning all your life. So from the first day of the first year you’re practising and learning at the same time.

Let me come back to the wrinkle in your question. I think that practice in UK, America and maybe here also teaching has become increasingly removed from practitioners. There are not enough practitioners teaching in these schools and the teaching environments that I’m part of and the ones in Dublin I was educated (I was educated by people who worked in Louis Kahn’s studio, Mies van der Rohes’, James Stirlings’, they were present to me as teachers, and they had their own practice and they taught me how to become a practitioner almost through witnessing them at work in the studio). Now, many are coming from a purely theoretical background and they see practice as something entirely different. What I like about what I’ve seen in Romania, especially at this conference, is that a lot of the students are taught by practitioners.

CF: You are working towards building a learning community rather than, as you said before, preaching. However, this model still exists, there are architects who teach having in mind to leave a legacy behind. What makes you do something different?

NM: There’s a little premise behind your question that I’m not sure I agree with: I don’t think that’s the wrong way of teaching. I think there are many people who have been taught that way and benefited enormously from learning in an environment like that. So the pupil-master relationship that you described is not in itself the wrong way to teach. And I think that a lot of people found that relationships like this were quite fruitful for them. It suits a certain kind of pupil and a certain kind of master. What makes me do things differently is that I wasn’t like that as a pupil, so I cannot be like that as a teacher. But I see other excellent students and teachers who are like this and the diversity fills me with joy.

The reason of why I don’t teach like that is that I am not inclined to. I like more to find out what somebody else thinks than to tell them what I think. I find it more interesting, I’m bored of my own conversation. I like to get information from people.

What we do is we set an environment to say „show us what you’ve got, bring the things that you’ve dreamt of” and what I like to think is that we’re good at coaching I would call it. Something like ‘oh, if that’s something you think of doing, can I show you this resource, or this…’ it’s more like helping them structure things and help their ideas flourish. And the point is that that’s not done out of generosity, because as I’m watching that flourish I think to myself ‘oh, that’s a learning opportunity for me as well’.

CF: Stefan Ghenciulescu, the chief-editor of Zeppelin, recently said that he’s more of a midwife than a master, quoting the Greek architect and teacher, Elia Zenghelis.

NM: That’s a very nice comparison, I’m very pleased you brought that up. I’ve just spent some time in conversation with a group of students and they all said he’s the most charismatic teacher they ever came across. So it’s good to know that you can be a charismatic midwife.

My longest teaching practice was with Yeoryia Manolopoulou with whom I taught at UCL Bartlett for over 20 years and we used to joke with each other (I’m a propositional teacher and she’s a questioning teacher): I would go ‘oh, so you could do this and you could do that’ and she would go ‘but why?’ [laughs]. We’ve always described our teaching as driving a car with one person pushing the accelerator and one person has their hand on the break. So I think there are different ways of teaching and often what students are really doing is looking at you thinking to themselves ‘oh, so you could be like that, or you could be like this…’.

CF: What would you say students’ relationship with craft is today?

NM: That’s complicated. The students that I teach… they have an amazing workshop… maybe less so now…with all these geeky digital tools. But the best ones are going down to the workshop and working with real materials and making very beautiful things with their own hands, and so there’s a connection to craft. And that’s been a strong direction in my teaching. I do think it’s beginning to change a little bit. The students haven’t yet found a way of being really creative with them, or not all the time. I would also make a distinction between the craftsperson who makes things with their own hand and the architect whose role isn’t to build everything themselves. I think what the architect is already learning what to do is to be with makers, and to retain the integrity of their practice in the presence of these other more direct material practices. And I think this balance is not always understood. It should be that when the maker gets the architect’s drawing, they should know exactly what the architect knows — like when you go to Ikea and you get the instructions. You think ‘how much the person who wrote them anticipated the kind of questions I have to ask while I’m making this object? It’s quite a simple arrangement and the architect’s job is to understand enough about the process of making to know what you can and cannot do and then show the builder what you want them to make with an understanding of the questions, dilemmas and predicaments that would be produced. And the drawing somehow, if it’s a really good drawing, has that understanding in it. It’s like a good map. If you look at the map and you know it’s a good map but you can’t understand it, then you think ‘the problem is with me, not the map’. And I think a really good architect’s drawing has this sense of transparency and legibility. And we are not saying ‘we can make it, we can craft it’, but that we understand enough about the worlds of people who make and craft things that we can synthesise all these forms of craft together.

CF: Do you think we can understand this much about other people’s worlds without having experienced them firsthand?

NM: I do think in architecture schools it would be good to think about that a little bit more. We used to have something called technology studio every week, where we would make a working drawing. It started off in the first year with drawing an axonometric of a brick all the way to the fifth year when you were doing complete working drawings of your own buildings. It was really good because the people they brought into technology studio were not design studio teachers. They were people who were technically interested in building, so they would come in and, in those days, they would poke at your drawing with the stem of their pipe saying ‘what is that for, how does that work, how would you fix that?’ I think that side of architecture is something that should be taught so that when you come out you have the sort of dexterity expected from a surgeon. Even if it’s not manual dexterity, it should be mental dexterity that you could draw a building that could be made and is perhaps not sufficiently taught in architecture schools anymore.

CF: Would you say that materials call for a specific form, like Louis Kahn used to say, ‘What do you say, brick?’

NM: I mean there’s a mystical side to Kahn which, although I’m a great admirer of many aspects of his work, I don’t quite buy into. So, I mean, that geometrically, and in terms of his description of materials, there’s what I would call a Platonic idealism at work. In other words, he’s reaching for an implied perfect form that’s geometric and serene and stands almost outside time and human custom and practice. So that’s the sort of transcendental side of his work that I’m a little bit suspicious of. I prefer his work when it’s more on the vernacular, I mean it metaphorically, more in human nature. If you take a piece of wood and ask it what it wants to be, the wood actually wants to go back and be a tree. The stone wants to go back to be a mountain, and you’ve arrested these poor things and you want to turn them into something else. So the thing you have to understand is not what the thing, in some ideal way, wants to be, you have to understand what it used to be and you interrupted. Because if you don’t understand what a piece of wood wants to be, you will get all sorts of problems: ingrain, moisture, uptake, staining, warping, twisting, because you haven’t understood its essential nature, its biological or geological nature of the material. So it’s this that needs to be understood. And then the other thing I want to be understood is how the way that we have encultured materials and the way we invest symbolism and meaning into materials. So that, if we sit in this room and look at this wallpaper, it’s not a completely innocent aesthetic experience. We understand the history of the 19th century, the social and cultural aspirations that are associated with the pattern and all that. So understanding a material is both a cultural thing and a sort of biological and geological thing. Less than the kind of canion idea that the material has some mystic vocation.

CF: It makes me think about the fox’s line in the Little Prince: ‘You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed.’

NM: I think I’ll take that away with me.

I love the name of your magazine. Can I tell you a Zeppelin story?

CF: I’d love to hear it.

NM: I don’t know if this is true or not, I’m only reporting it. I met my old professor …..??? On the road, he was over ninety and I was back in Dublin after a long while and he said ‘oh, would you come and have a bottle of wine at my house?’ So I came back to his house, he opened a bottle of wine and we sat chatting and he told me about when he was working in Mies van der Rohe’s office in Chicago. And I said ‘what was Mies like as a person?’ He said ‘oh, he was great fun, he was really jolly and relaxed and he used to take us back to his apartment in Chicago where the students and the staff would sit and have drinks and he would tell us stories.’ And I said ‘tell me one of the stories he told you.’ He said ‘I remember the stories from when he was in Peter Behren’s office, the architect from the 1910, with the AEG Turbine Factory, one of the great initiators of modernism. And in Peter Behren’s office at the time there was Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. They were all working there, so Mies told me. And Corbusier always took himself all too seriously and he was also very short sighted, so Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius made a drawing of a zeppelin on the window of the studio building looking out.

When he saw it, Corbusier went ‘Look! There’s a Zeppelin!’’

Níall McLaughlin Architects. Three projects

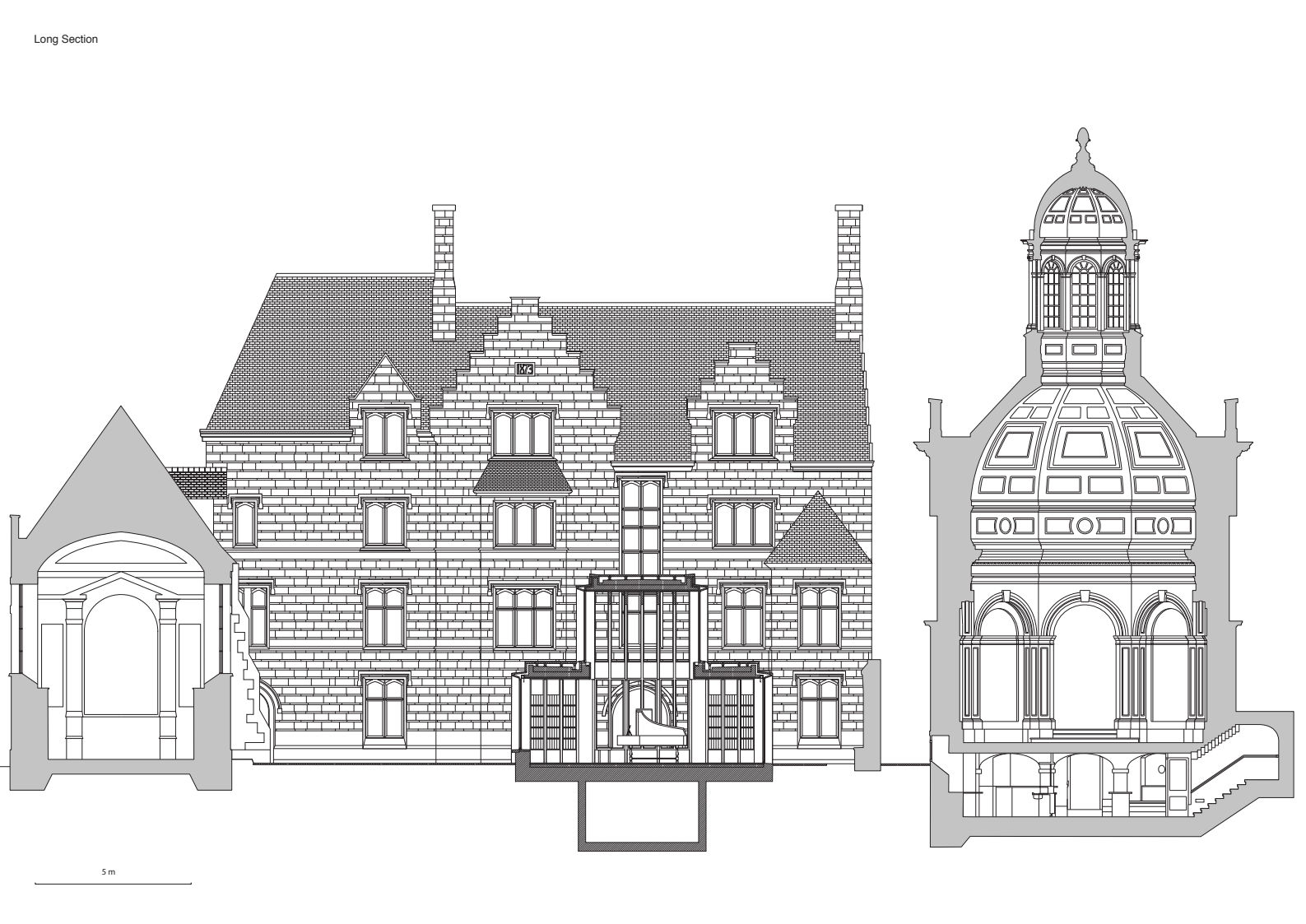

Balliol College Master’s Field Development

*Balliol College Master’s Field Development

*Balliol College Master’s Field Development

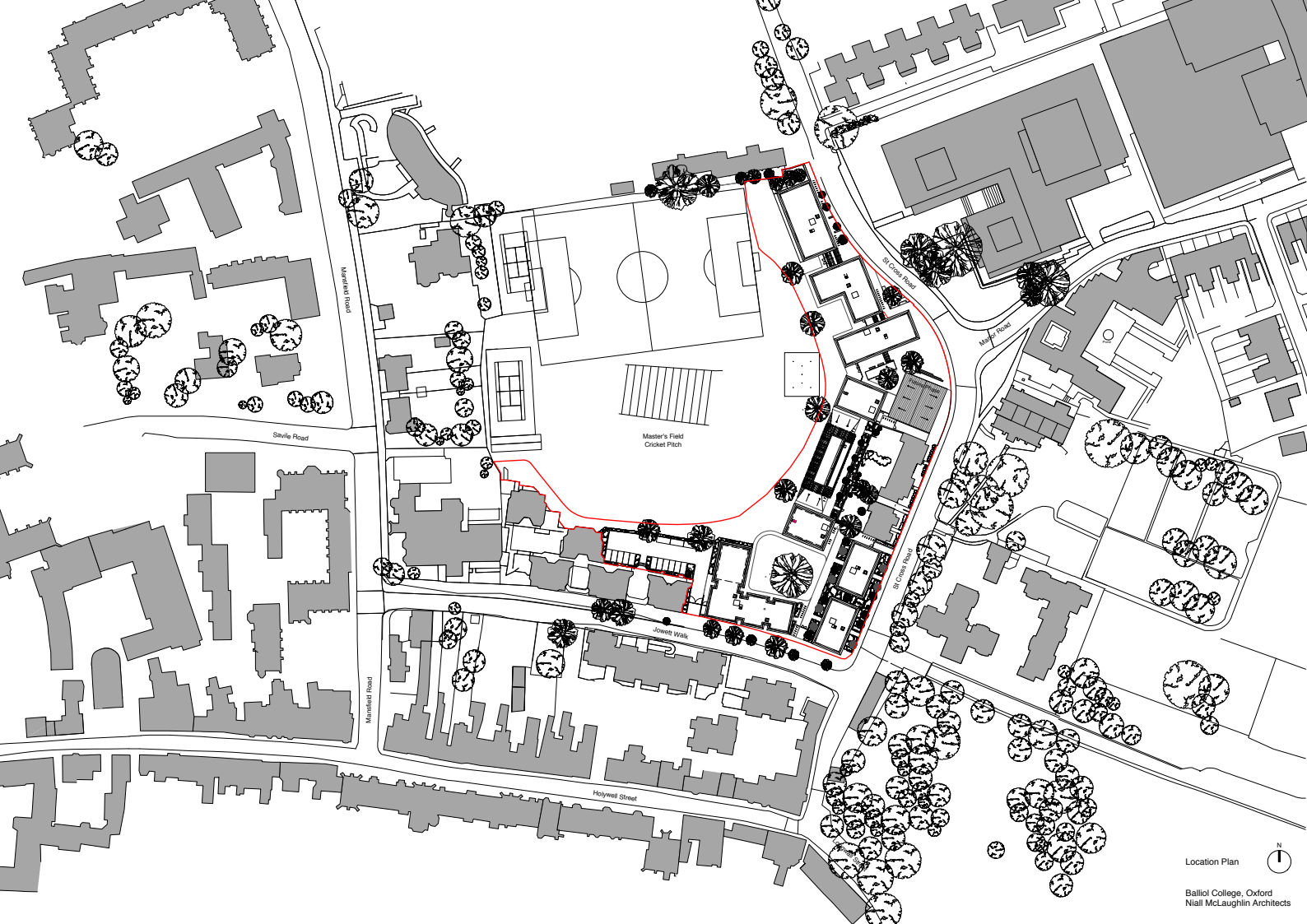

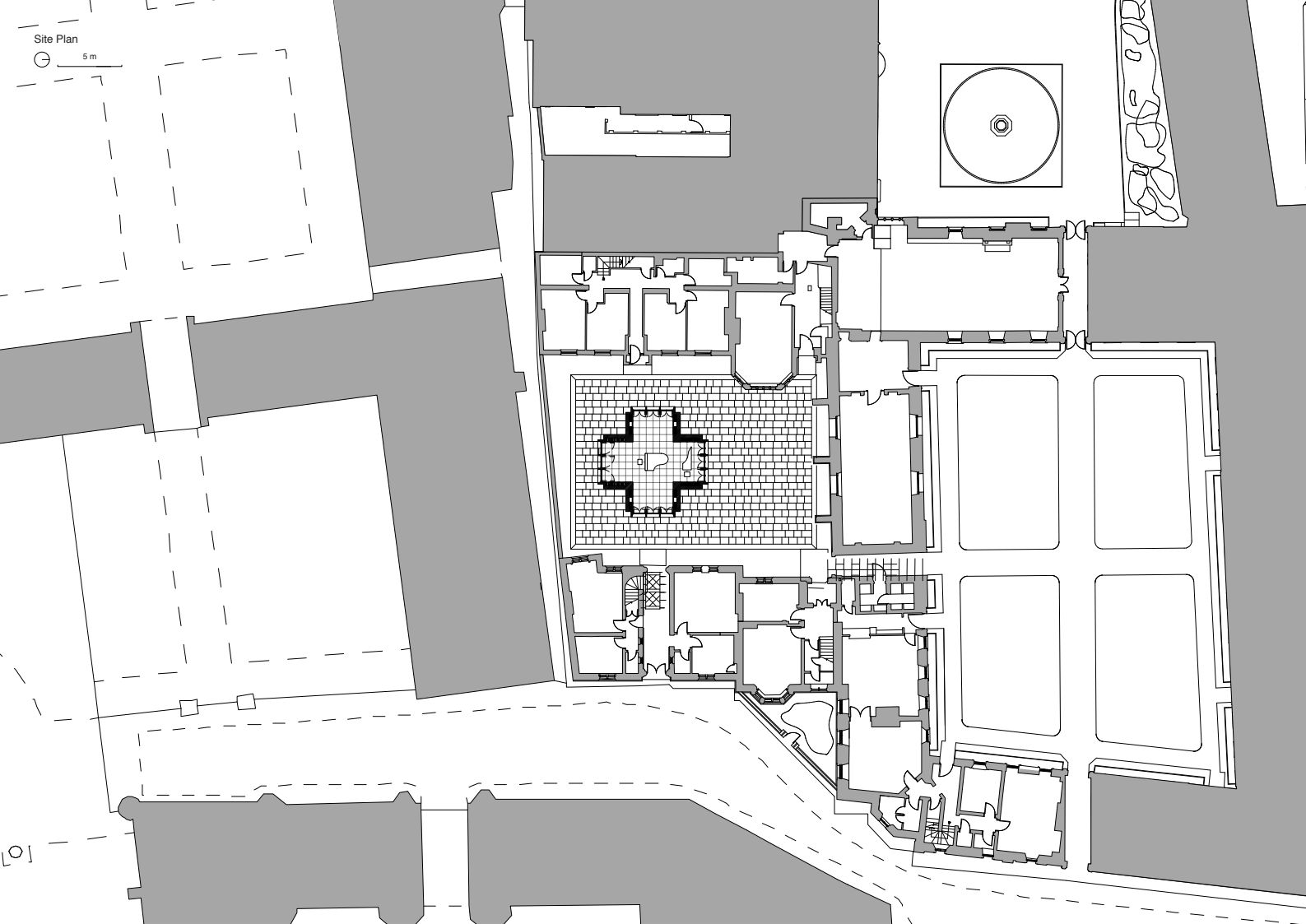

The Master’s Field development is a multi-phased masterplan comprising eight purpose-built student accommodation buildings, a professorial flat and a pavilion. The buildings frame a series of new landscapes including planted quadrangles, tree-lined paths and planted borders. Crucially, the project enables the College to accommodate its entire undergraduate intake on site.

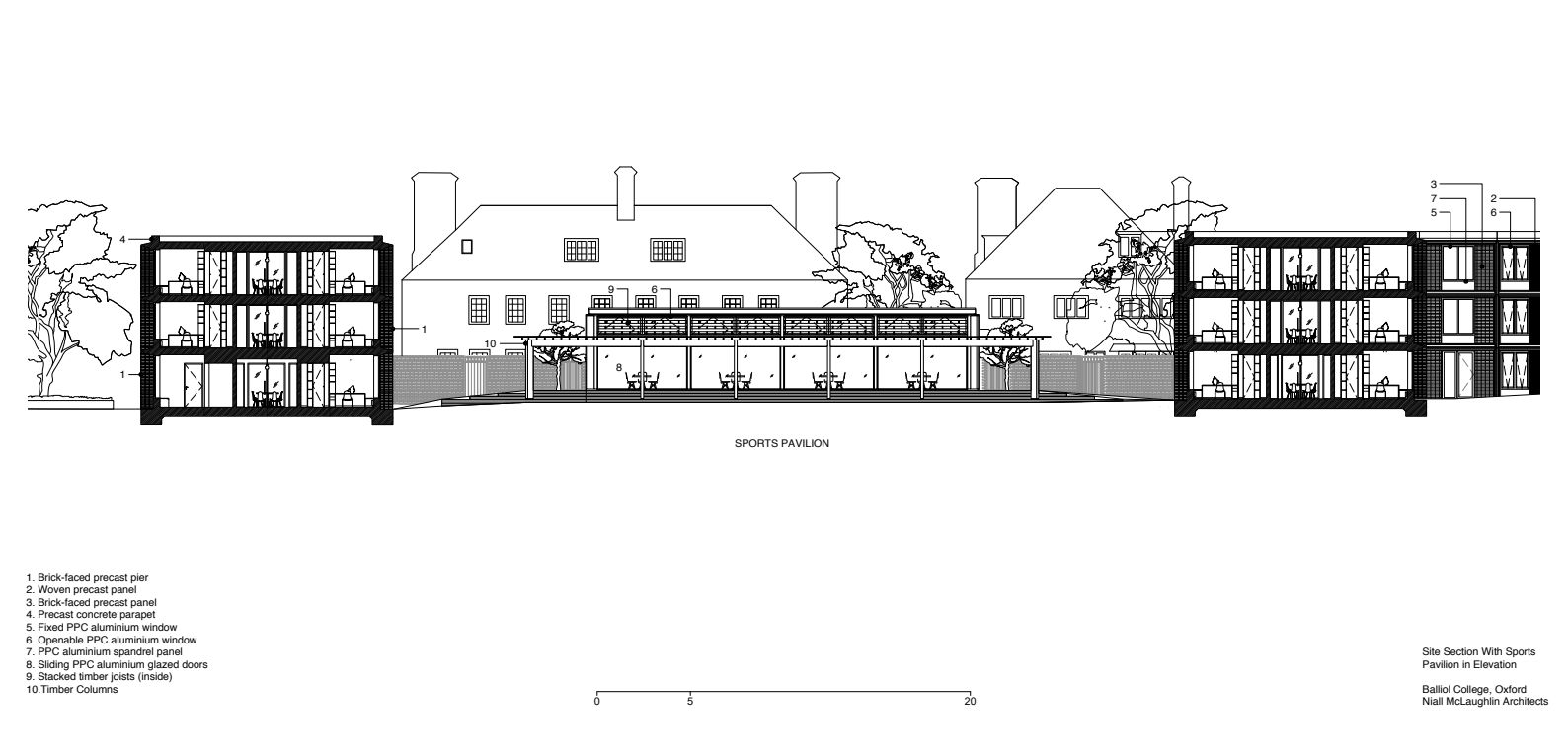

Low-rise buildings are arranged around the curve of a cricket boundary, joining an ensemble of existing student residences designed by McCormack Jamieson Prichard Architects in the 1990s. The project provides 225 furnished en-suite study bedrooms arranged in clusters, supported by common rooms, laundries, refuse and covered cycle storage areas.

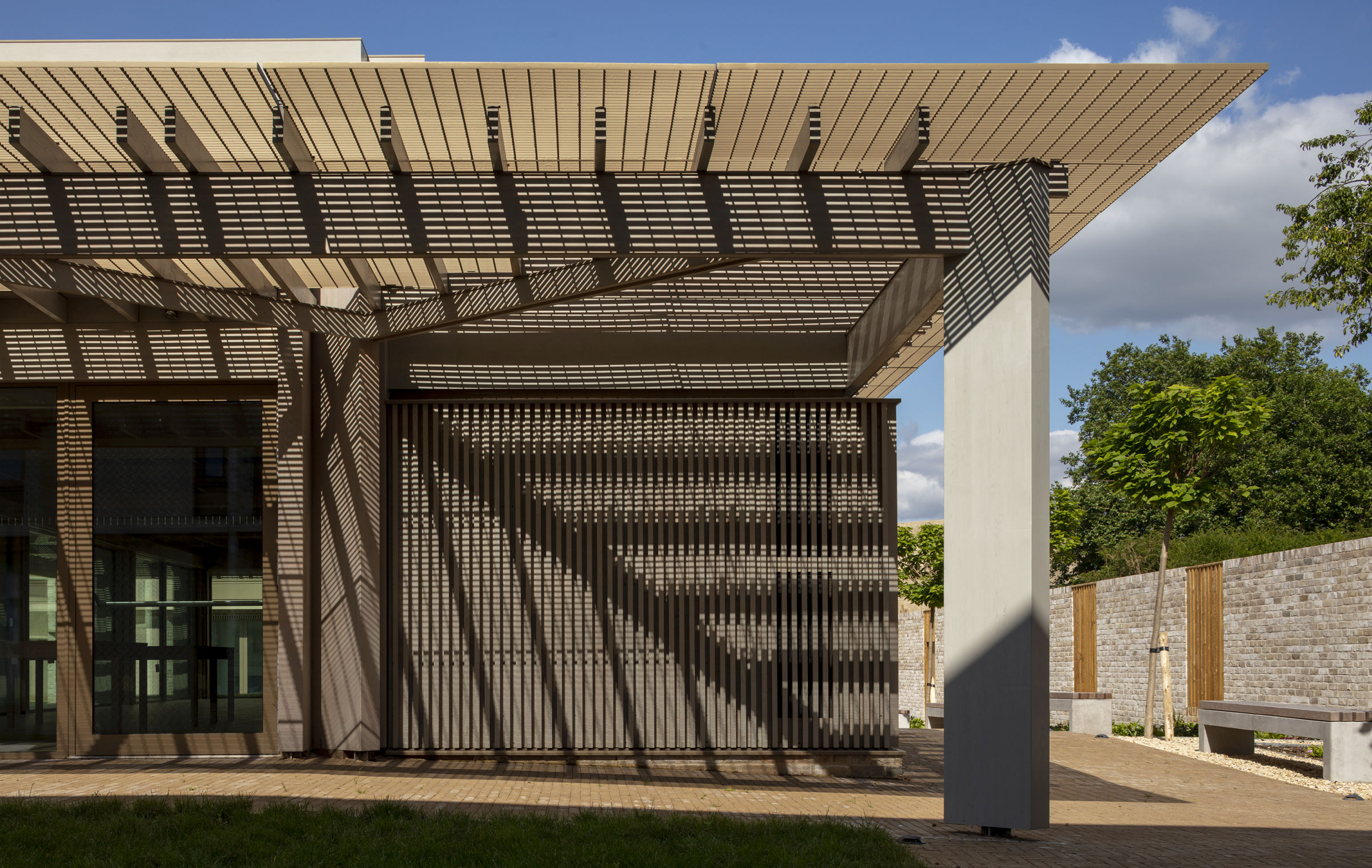

A centrally located sports pavilion overlooks the cricket pitch and houses a squash court, changing facilities and a multi-purpose hall. Its lightweight structure – made from sweet chestnut wood – frames views through sliding windows that lead onto an elevated covered terrace. Inside, the hall has an intricate stacked timber ceiling with integrated lighting. Balliol College wanted to create a development in the spirit of a traditional collegiate setting, placing student welfare at its heart. Their ambition was to minimise student isolation and cater for a range of academic vocations within varied bedroom layouts. This ethos underpinned the entire design process. The scheme delivers generous, often dual aspect, rooms with verdant views and bespoke joinery. Facilities to support a broad range of accessibility requirements are provided: anti-allergen surfaces, vibrating pillows, adaptable wet rooms, and evacuation lifts for full wheelchair accessibility.

The arrangement of buildings around the site responds to the pattern of student daily life. The bedrooms are set in clusters around localised social spaces. They are accessed through glazed stairways linked to shared kitchens or common rooms to allow impromptu social interactions.

This primary spatial arrangement informs the layout of rooms, buildings, ensembles of buildings around quadrangles, streets, and gardens. The buildings frame and animate outdoor gathering spaces. Windows are recessed within deep reveals to maintain the privacy of the individual in each bedroom. The buildings are dressed in a trabeated rhythm of brick-faced precast piers and lintels, which are organised in repeating bays correlating to bedrooms. Opening windows are held between precast panels cast in a woven motif.

*Ground floor plan, upper quadrangle

*Ground floor plan, upper quadrangle

The masterplan responds to a variety of existing historic buildings and complex site conditions. It mediates a shift in scale and typology at the edge of Oxford’s civic core from domestic terraced villas towards institutional buildings. Disparate bounding conditions are reconciled by adopting a common architectural language across a series of deliberately repetitive, yet modest scaled buildings. The consistent palette of high-quality materials was selected to complement the surrounding historic context. There is a subtle distinction between buildings facing gardens and buildings forming the edge of streets. Near busy roads, the student rooms are raised on solid masonry podiums. Gaps between buildings frame public views into the depth of the site. *Section through the common spaces pavilion

*Section through the common spaces pavilion

Delivered under a D&B Contract, the project embraces standardization and off-site manufacturing. We used prefabricated bathrooms, CLT / glulam frames, and prefabricated facades. Sourcing UK based suppliers allowed us to improve quality-control and reduce carbon impact and waste.

The design is based on a careful consideration of the needs of students at the scale of the individual rooms, spaces of connection, social spaces, gardens, paths and courts, reaching out to the wide urban scale.

Info & credits – Balliol College Master’s Field Development

Architecture: Níall Mclaughlin Architects

Contractor: Bam Construction Ltd

Consultants: Project Manager Bidwells

Mechanical And Electrical Engineering: Harley Haddow

Structural & Infrastructure Engineering: Smith And Wallwork Engineers

Quantity Surveyor: Gleeds

Planning Consultant: Turnberry Planning

Civil Engineering: Smith And Wallwork Engineers

Landscape Designers: Bidwells Urban Design Studio

WongAvery Gallery, Cambridge

The WongAvery Gallery is a music practice and performance space for Trinity Hall, Cambridge. The new building sits in the centre of Avery Court. It was originally the entrance court to the College, but lost this function following the creation of the adjacent Front Court. The aim of this project was not only to provide a much-needed dedicated space for music practice and performance, but also to rejuvenate Avery Court by relandscaping the court around the new building.

Avery Court was chosen as the site due to its proximity to the College chapel, however it presented a number of challenges. The court is surrounded by Grade 1 and 2 Listed Buildings, including the chapels of Trinity Hall and Clare College, and is therefore a highly sensitive historic setting. Light to existing window openings had to be maintained and study bedrooms protected from noise. Finally, the construction site was accessible only via a narrow pedestrian passageway, severely limiting access for materials and plant during construction.

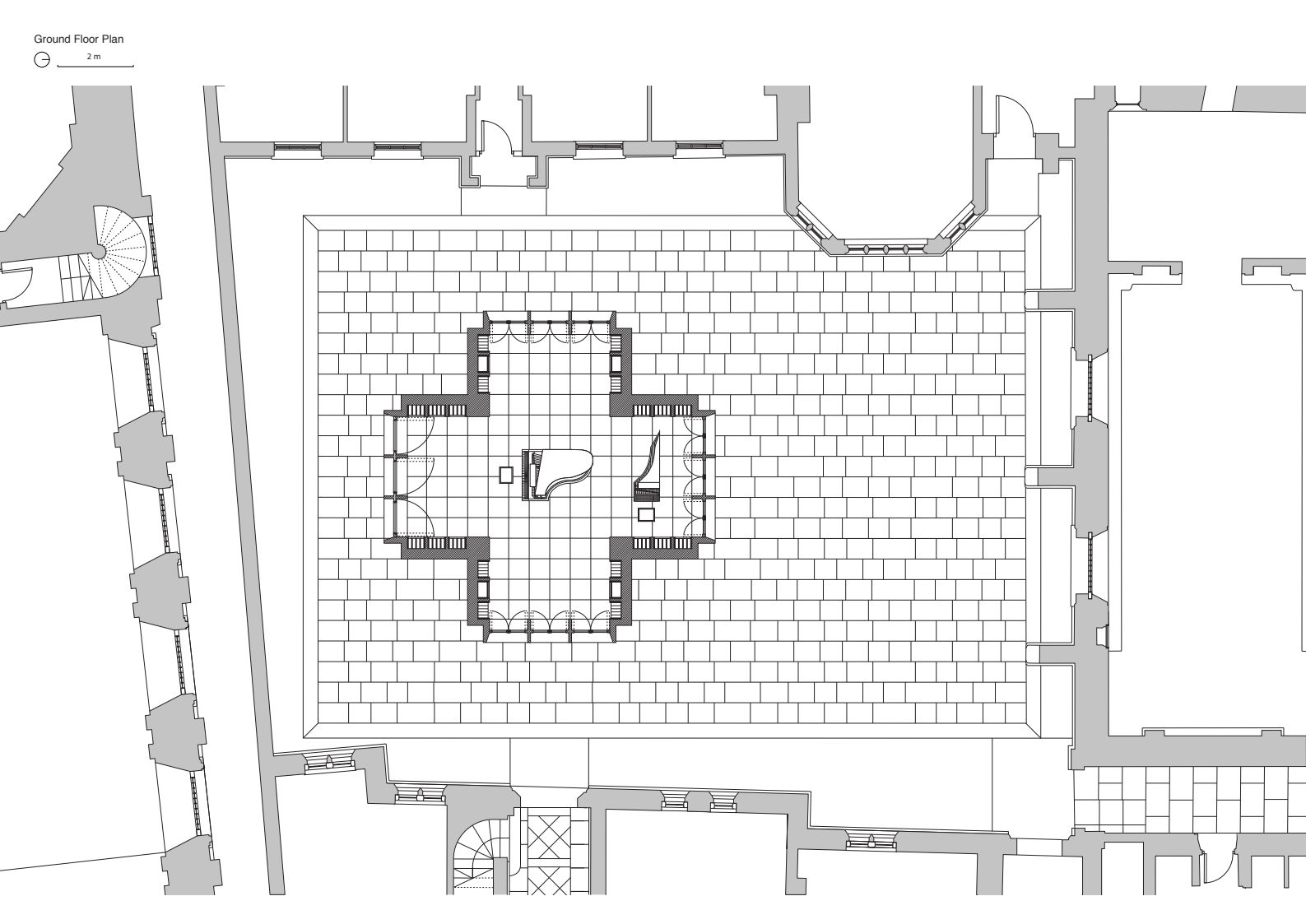

The architectural solution was to build a free-standing pavilion which would form the centrepiece for the relandscaped court. It is a tiny, monumental object, the singularity of which plays against the accretive complexity of the surroundings. While this strategy avoided obscuring existing window openings, building within college courts is without precedent in Cambridge and in light of the highly sensitive historic setting the planning application was reviewed by Historic England at a national level. The Gallery is a loadbearing construction made of Portland stone and precast concrete. It is a composition of cubic forms, based on a Greek cross plan. Performances take place in the centre, with audience seating in the bay-windowed arms of the cross, the flanking walls of which are lined with shelves to store sheet music. Over the crossing a glazed lantern brings light into the centre of the plan, providing additional volume and internal surface area to improve the acoustic characteristics of the space. The bay windows can be fully opened, enabling the Gallery to be used as a bandstand for openair performances.

The Gallery was also built to house the College’s harpsichord. This highly sensitive instrument requires strict environmental control to stay in tune. The four corners of the Greek cross contain vertical ducts leading from a plant room concealed beneath the Gallery that distribute air at the correct temperature and humidity.

The landscape design by Kim Wilkie sets the building on a large central paved area, surrounded by borders filled with predominantly green shrubs and climbing plants. The lighter coloured Portland stone of the Gallery stands out against the greenery and the darker, honey-coloured stone and brick of the existing buildings.

The addition of the new building greatly improves the College’s offer for students and staff participating in or studying music. By making visible the previously hidden activities of the College’s musicians it also helps raise awareness of music-making in the College and enriches the cultural life of the College as a whole.

Info & credits – Song School

Architecture: Níall Mclaughlin Architects

Gross Internal Area: 73 M2

Client: Trinity Hall

Contractor: Barnes Construction

Structural Engineer: Smith & Wallwork

Mechanical And Electrical Engineer: Max Fordham

Acoustic Engineer: Gillieron Scott Acoustic Design

Landscape Architecture: Kim Wilkie

Stone Consultant: Harrison Goldman

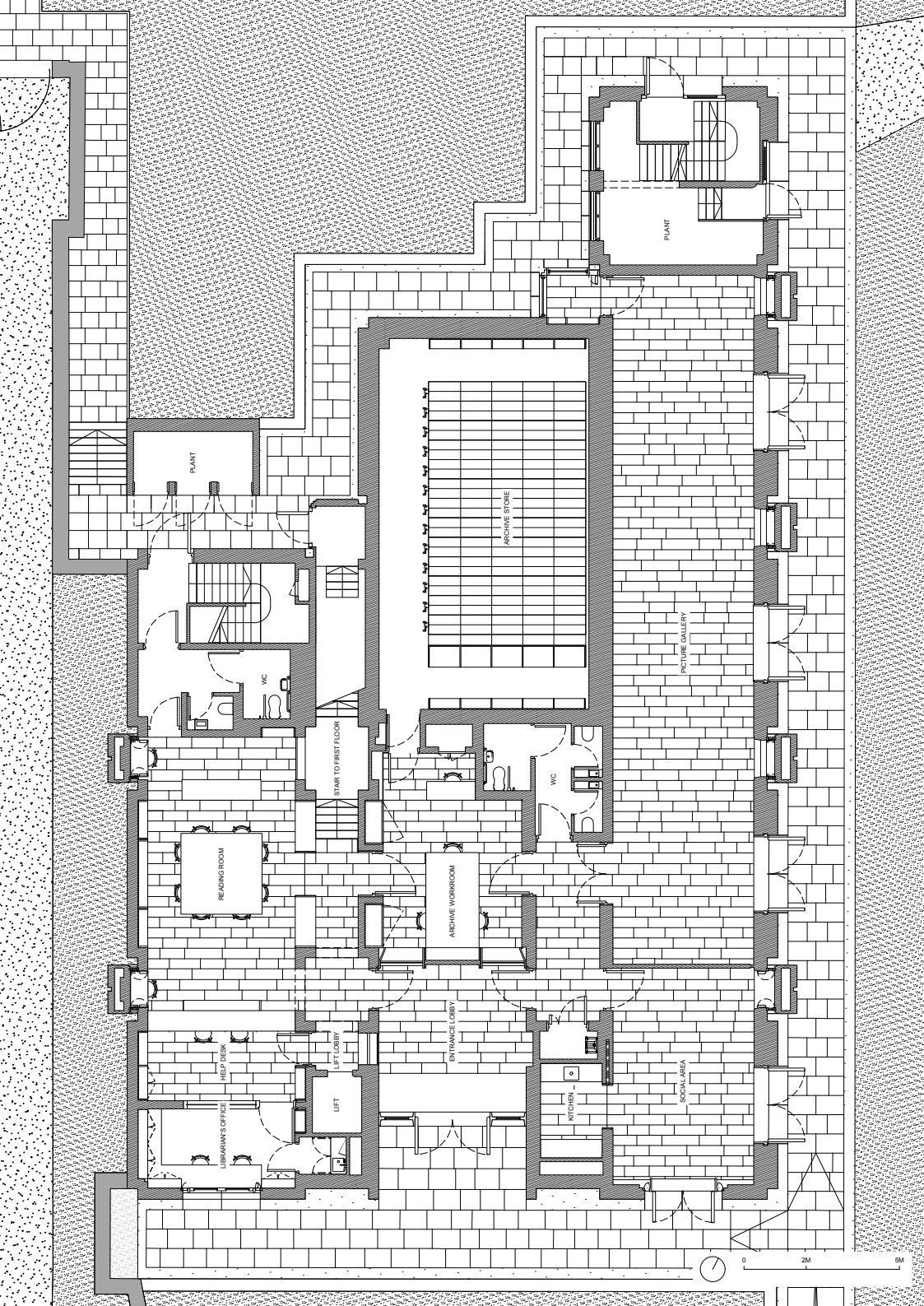

Magdalene College Library

We were appointed to design Magdalene College’s New College Library through a competition held in 2014. The new building replaces cramped and poorly equipped facilities in the adjacent Grade 1 Listed Pepys Building with a larger library, incorporating an archive facility and a picture gallery.

The new building is sited in a highly sensitive historic setting, along the boundary wall between the enclosed space of the Master’s Garden and the more open space of the Fellows’ Garden. Its placement extends the quadrangular arrangement of buildings and courts that developed from the monastic origins of the college site.

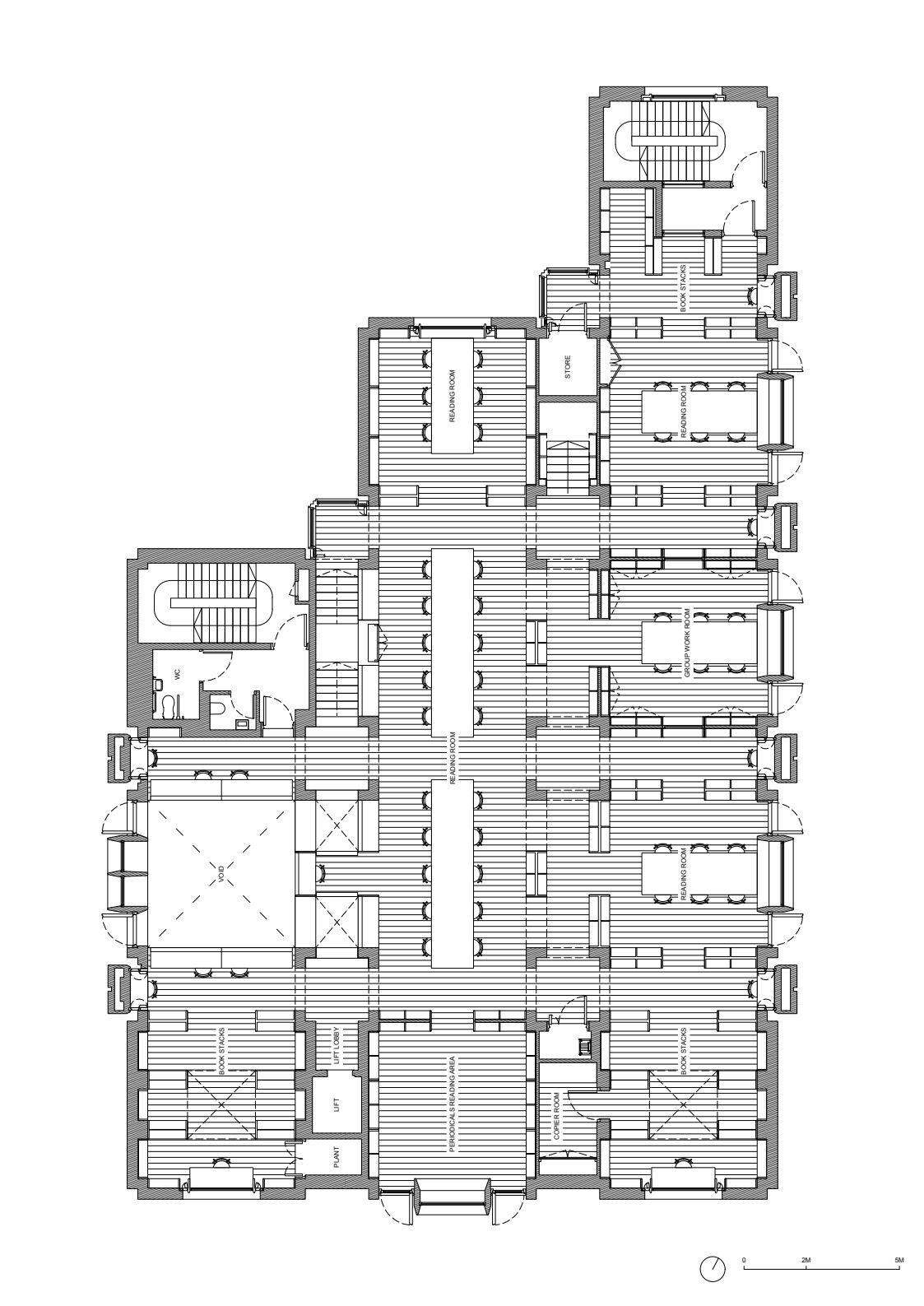

The library is approached from Second Court, through a little doorway and out under an old Yew tree. From this shady corner you sense the presence of the river opening out at the edge of the lawn. We wanted to make the building a journey that gradually rose up towards the light. On the way up there would be rooms, galleries and places to perch with a book. At the top, there would be views out over the lawn towards the water. We wanted to create a variety of ways for someone to situate themselves depending on inclination. You might sit in a grand hall, a small room, or tuck yourself into a tiny private niche.

For us, good architecture plays variety of experience against underlying order so as to produce harmony. The new library is based upon a logical latticework of interrelated elements. A regular grid of brick chimneys supports the floors and bookstacks and carries warm air up to ventilate the building. Between each set of four chimneys there is a roof lantern bringing light down into the spaces below: air rising and light falling. This regular array produces a natural hierarchy with narrow zones for circulation and wide zones for reading rooms. The delineation of load-bearing brick vertical structure, supporting spanning engineered timber horizontal structure is used to reinforce the organisational scheme. This creates an underlying pattern of warp and weft that we hope can be understood intuitively by people using the building.

The materiality and form of the new library are derived both from its context and from the College’s brief to make a highly durable and sustainable building. The older college buildings are of load bearing brick, with timber floors and gabled pitched roofs structures. Brick chimneys animate the skyline and stone tracery picks out the fenestration. We tried to make the new building from this set of architectural elements. We used timber instead of stone for our window tracery, which will weather over time to become a silvery grey like the stone. We worked carefully with our builders to find a variety of bricks that would match the tapestry-like quality of the older College buildings. At the same time, this is a modern building that employs innovative passive ventilation strategies to minimise energy in use and engineered timber structure to reduce carbon embodied in its construction.

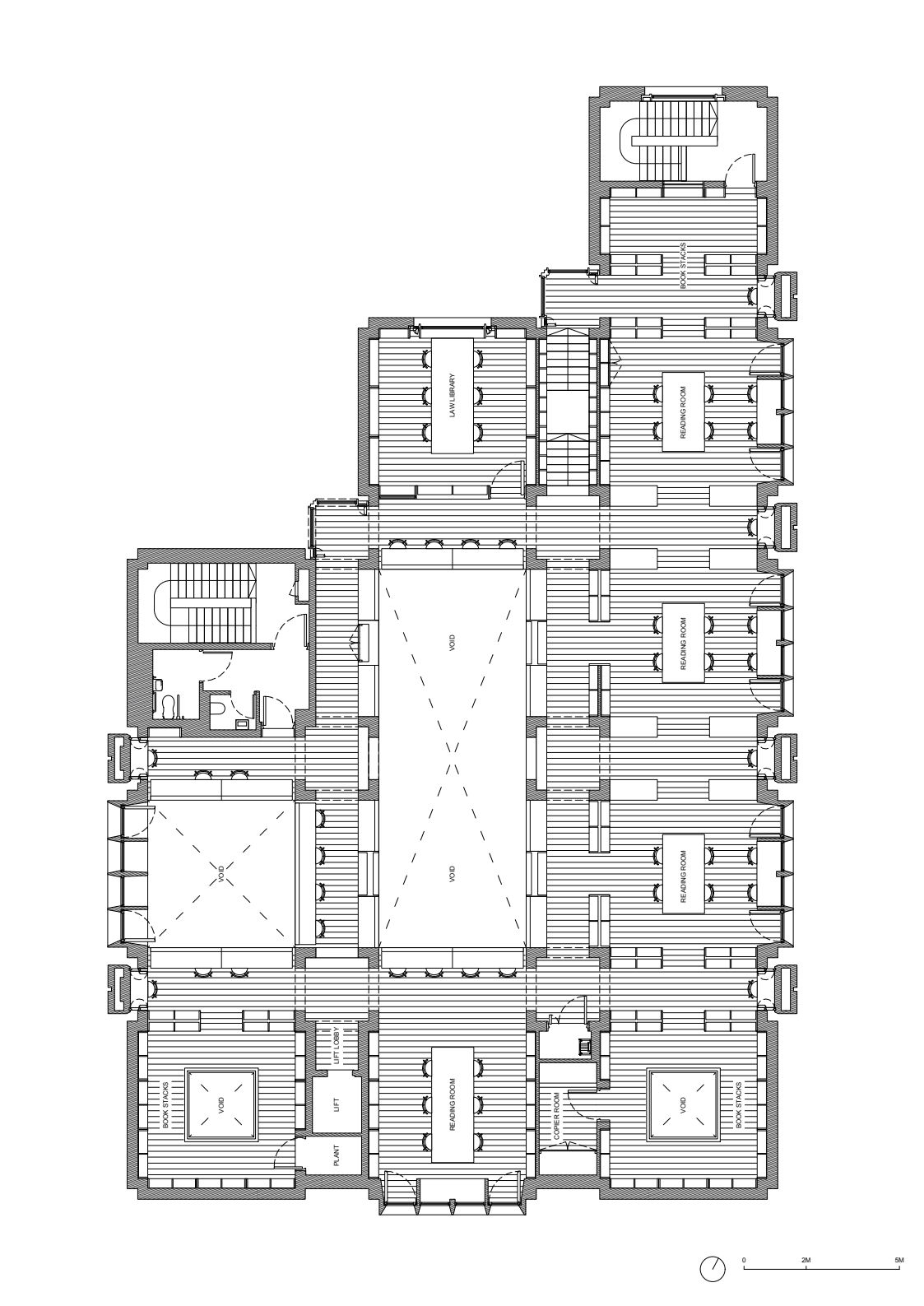

*Ground floor plan

*Ground floor plan *1st floor plan

*1st floor plan *2nd floor plan

*2nd floor plan *Section

*Section

*FAST (Festival for Architecture Schools of Tomorrow) is an annual event initiated in 2023 by the Romanian Order of Architects (OAR), aimed at creating opportunities for collaboration between Romanian architecture schools and encouraging dialog between academic education and professional practice. The festival brings together the country’s five faculties of architecture – Timisoara, Cluj-Napoca, Oradea, Iasi and Bucharest – and extends collaboration regionally and internationally.

The first edition took place in 2023 in Timișoara, in the context of the city being European Capital of Culture, and the second edition took place in 2024 in Cluj-Napoca. It was called “Diversecity” and explored the diversity of phenomena affecting contemporary cities and possible directions for a sustainable future. Sub-themes of the festival were cultural heritage and city identity, density and sustainable growth, and ecology and equity in spatial planning.

FAST is aimed at students and teachers of architecture, as well as practicing architects, policy makers and the general public interested in the quality of the built environment. Through the festival, the OAR creates a platform for dialog and collaboration for the future of the profession and our cities.