Text: Cristian Bădescu, Vlad Dumitrescu

Foto: Vlad Dumitrescu, Marius Vasile, Cristian Bădescu, arhiva fam. Cocioabă

The youth of our city1

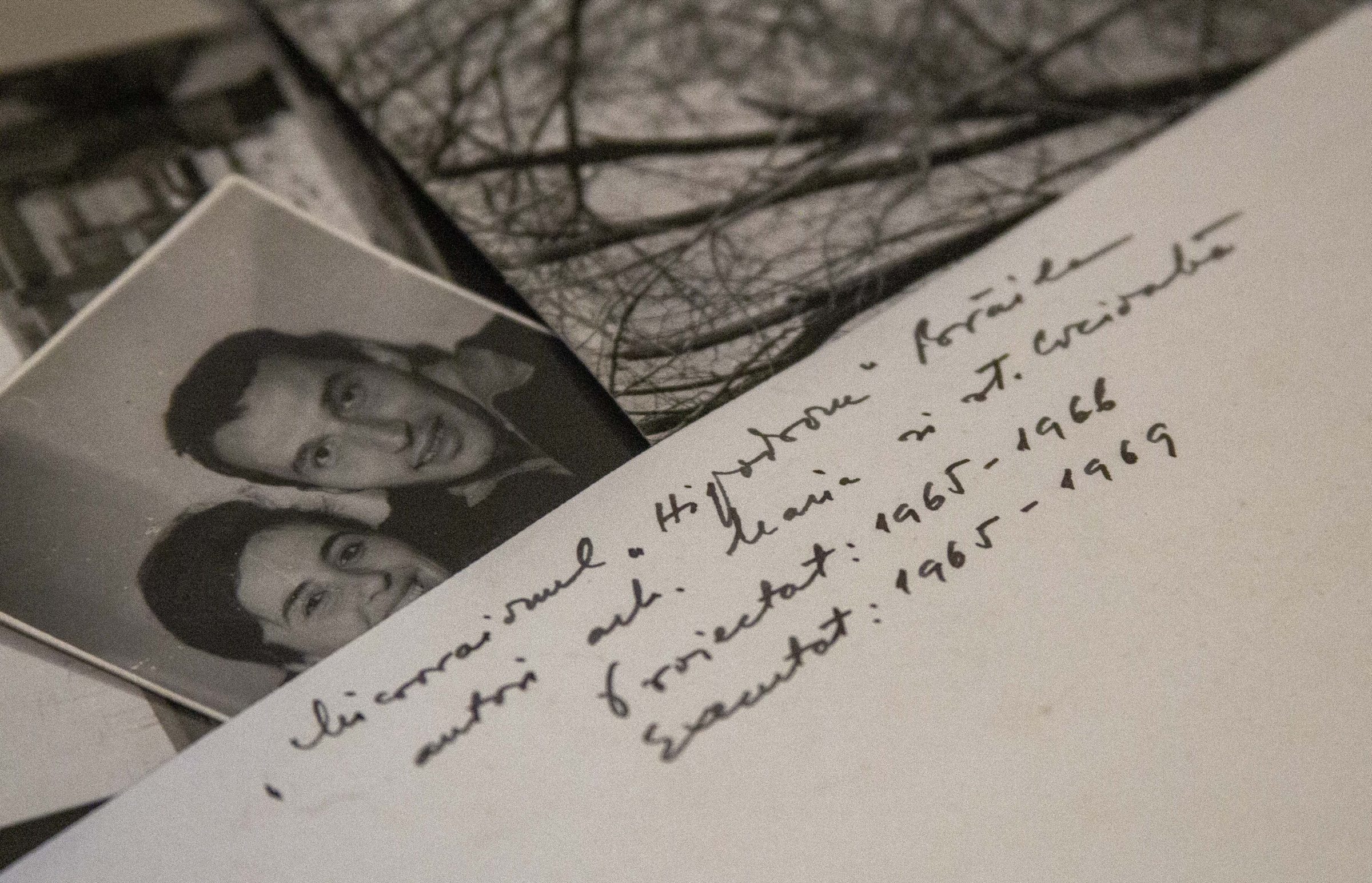

“I found a picture of Fane Cocioabă and your grandfather,” my grandmother said, holding out an old photograph. “It’s from college or afterwards, from the institute. I don’t remember.” The picture that my grandma was holding was showing Sterea Bădescu, my grandfather and his peer Ștefan Cocioabă, alongside a group of other young architects. We were looking for the photo as part of my research into the Hipodrom Housing District in Brăila.

From its very beginnings the whole project was a strongly autobiographical one as the lush and winding Hipodrom is where I spent most of my childhood. Moreover, although it was the image of my grandfather hunched over a drawing board that inspired me to become an architect, I had never delved deeper into what the profession meant to him and his generation.

Reconstructing the history of the Hipodrom District and the story of those who designed it, Ștefan and Maria Cocioabă, also reveals fragments of the history of the practice of architecture in Romania in the 60s.

The Cocioabă couple graduated from the Ion Mincu Institute in 1960 and were immediately assigned to D.S.A.P.C. Galați. At the beginning of their careers, they were the authors of a series of projects for the institute, including a housing complex in Focșani and the Brateș Casino in Galați. Ștefan Cocioabă was known for being creative, charismatic, and passionate about the arts. He was credited not only for his architectural work, but also for the fountains within a group of blocks on Galați Street in Brăila, built in 1964. Along with architecture, he had a deep passion for caricature, his drawings being published in magazines of the time such as Flacăra, Romania Liberă, Contemporanul or Urzica.

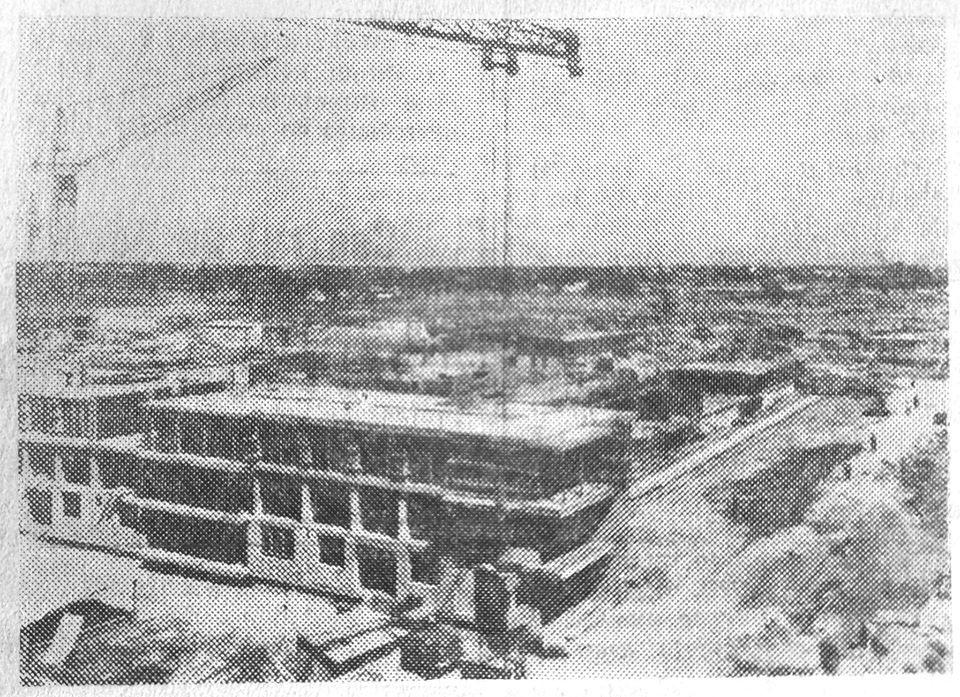

The photos of the neighborhood under construction found by Suzana Cocioabă, their daughter, illustrate a warm, passionate and strongly committed character: present on the work- site, ambitious and excited for what was to be built.

“He was convinced that art, regardless of the form in which it manifests itself, should not demolish the being, but build it inside as in a beautiful and inimitable temple.” This slightly romanticized description from the epitaph written by Nicolae Grigore Mărășanu in Urzica magazine conveys a portrait of Ștefan Cociobă that is confirmed by most of his friends. Maria Cocioabă, Ștefan’s wife, was co-author of most of the projects they worked on together. She was unmistakably mentioned on the back of each photograph from the family’s personal archive through the phrase “authors: Maria and Șt. Cocioabă”.

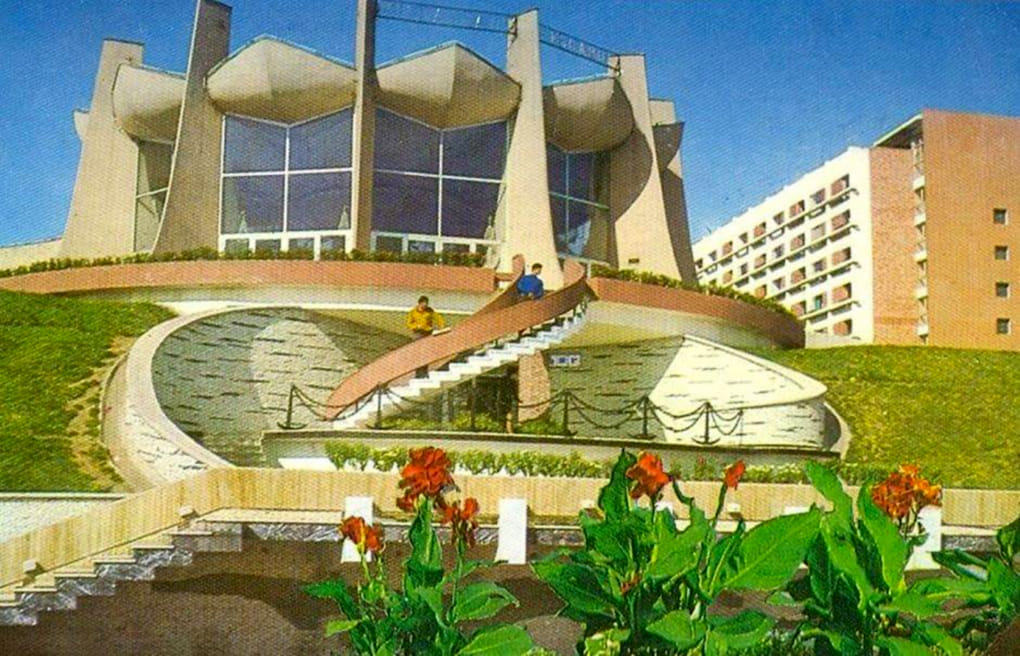

The “Pescarul ” restaurant in Galați was the Cocioabăs’ first reference work. Designed from the very beginning as a landmark on the Danube’s embankment, it departs from the purity of functionalist modernism which characterized their first works, and leans towards an architecture with expressive reinforced concrete, various textures and materials.

The plan is free from the constraints of typified sections imposed in other programs such as residential architecture. Curved lines are used exclusively, a choice justified at least formally by the author in Arhitectura Magazine by the requirements of the program. The project received national recognition through the prize awarded by the Union of Architects in 1965. It was also at that time that the design of the Hipodrom District began, marking the return of the two architects to their hometown of Brăila.

In just a few years, a small town arose here

The Hipodrom district was the first large-scale neighborhood of Brăila built during the socialist period. Prior to its construction, new buildings were mainly concentrated in the representative areas of the old city fabric. The local press reported that it was intended to house one seventh of the city’s total population upon completion. Beyond the numbers, photographs of the neighborhood were constantly published in the local newspaper “Înainte”, showcasing the finished representative blocks or under construction sites..

Between 1965 and 1970, we found 70 images, articles or mentions of the evolution of the work – site, often placed almost advertorially, unrelated to the rest of the content of the respective issue.

The context in which the young architects of the 60s began their careers was one of social openness and a change of direction compared to the previous decade. Socialist Realism was already consumed and architects had begun to recover the principles of modernism. All this was superimposed on a great construction-boom – the country was transforming into a big construction site. Although the project has gone through a series of redesigns and expansions, we find its original urban planning intentions in the images with the model and the plan published in Arhitectura Magazine4. The project was made possible by the availability of large and mostly barren land of the Hippodrome.. This allowed for a design that closely adheres to the modernist principles of urbanism, featuring ample green spaces, well-planned composition of building volumes, and minimal car traffic routes.

Although the vast majority of housing complexes built during the communist period are now associated with the image of working-class neighborhoods, with minimal areas and an economy of resources, Hipodrom seems to have been intended to address a certain form of “middle-class” of the period , thus receiving greater attention and resource allocation. Newly graduated engineers, doctors or teachers, they were all assigned to the neighborhood, often without their will or consent.

The social profile of the first inhabitants is also confirmed by the first principal of the local school who proudly stated that in the first years (the school was inaugurated in the second half of the 60s) most of the students had parents with higher education.

The power of the designers is however limited, the apartment plans being typified and imposed by the I.P.C.T. Their influence is visible in the details, where some themes and intentions from the “Pescarul” restaurant are repeated. Most buildings use brightly colored mosaic and breaks in the plane of the facade to create rhythm, variety, and identity in a juxtaposition of buildings that essentially repeat the same plan section.

The true experience of the neighborhood, however, is not necessarily related to the architectural detail, but rather to the impressive extent of the green areas.. The generosity of the distance between the blocks not exceeding five storeys has immersed the system of undulating alleys in an abundance of vegetation.

As an adult, it is one of the most labyrinthine and confusing neighborhoods in the city, but as a child, it seemed both enormous and enigmatic, with areas slowly revealing themselves as one moved away from their block, while the mosaic was more valuable detached from the facades, being collected and used for games.

Within the vast expanse of blocks and verdant spaces, two categories of landmarks emerge that demonstrate a clear deviation from the typical design and construction practices of the time. The first category is represented by the entrances of the single room apartment blocks, which were the first structures built in the neighborhood and are located on the street with the highest visibility, appearing in numerous newspaper photos. Each of the five units boasts a unique mosaic designed by a particular artist, and devotes a significantly larger area to the staircase and entrance than any “economic” criterion would have dictated.

Moreover, the staircase is fully glazed, a feature that has escaped largely untouched by modifications and energy efficiency improvements to the present day. The enthusiasm of some of the original residents was evident as they shared with us their excitement upon moving into their new apartments in a housing district that resembled, according to them, a seaside location.

The second category of landmarks is somewhat surprising, given that they are related to a utilitarian function. In order to meet the heating needs of the entire housing district, four smaller heating plants were built. However, rather than simply fulfilling their functional requirements, the architects chose to turn them into iconic structures.

Their need for a chimney became the perfect opportunity to create four distinctive architectural features which were skillfully integrated as integral elements of the urban landscape. With a double height compared to the surrounding 4-story blocks, they were placed in prospective ends, and over time became landmarks for residents.

It is uncertain whether these small digressions and collaborations with artists represent avowed dissent, as happened in the era in both Eastern Bloc and Western countries, often as a reaction to political constraints or the lines of modernist architecture. The decision to collaborate with the five artists – Gheorghe and Viorica Iacob, Pia and Napoleon Costescu, and Mihai Horea – arose from personal friendships rather than a shared manifesto.. Additionally, there is a possibility that dissent was simply tolerated. The aforementioned charisma of Ștefan Cocioabă put him in good relations with the political decision-makers from the outset, ultimately leading to his appointment as the head of the newly established design institute in Brăila, a position later assumed by his wife.

A short time ago, the work of builders was pulsating here

After the initial “pure” stage, the original plan underwent changes, redesigns, and densification during construction. An anecdote from a participant in the welcoming delegation from Brăila says that, upon seeing the buildings, Ceaușescu said: “What are we building comrades, workers’ quarters or villas in parks?”. The bourgeoisie had moved to the block and the neighborhood had become too cramped to hold it.. The zoning board 239 / 968 indicates an increase in the capacity of the neighborhood up to 15,000 inhabitants. Although validated by Ștefan Cocioabă, it is unclear which were his true feelings regarding this densification process. Perhapswe can find some clues in the way the project was published in Revista Arhitectura, with the original plan and layout, devoid of the new blocks added later. The original core of the neighborhood has been well preserved from an urban point of view, with post-December interventions mostly affecting balconies, finishes, and mosaics. However, through the vegetation that has grown almost uncontrollably in the last 60 years, the neighborhood paradoxically managed to fulfill, at least partially, the modernist ideal – free buildings in a generous green space.

It is these current and past features along with the stories behind the neighborhood that have constantly fueled our research. On the one hand, the story of the Cocioabă couple is one that humanizes the black and white pictures and the political undertones of the information found in the archives. It is heartwarming to imagine a young couple of architects looking eagerly at the model of their future project, a project that had only been enriched with a series of mosaics after a talk between friends. At only 30 years of age, born in a historical context with its economic, social and cultural particularities, the two architects managed to generate an urban fragment with qualities that are still present today, such as the generosity towards the public space and the good measure of living, qualities almost unheard of in new real estate developments.

Beyond nostalgic glancesthough , the study of a neighborhood like the Hipodrom and others like it raises many questions about the quality of place and public space today. Perhaps, sixty years after its construction, it is possible to move beyond endless discussions of socialist ensembles’ shortcomings and instead focus on the resources they were able to offer and continue to offer.

This text is based on research carried out by the “Hipodrom Brăila” project team, initiated at the beginning of 2020 to capitalize on the built and cultural heritage of the neighborhood. The project aims to lay the foundations for a strategy to reanimate public space based on the needs of the community and local history, in collaboration with the authorities and residents. The extended team of the project from 2020 to 2023 includes Raluca Mihai, Lea Rasovszky, Nicoleta Cruceanu, Carmen Țigău, Vlad Dumitrescu, and Cristian Bădescu.

The archive pictures in the article come from the Cocioba family Personal archive and were offered by Suzana Cocioabă, the architects’daughter.