A great, small memorial, subtle and open to interpretations, worlds away from the emphatic, top‑down ensembles that seem to have come back in later years. Levente Szabó is himself an architect with experience in memorial projects. He places this project in a wider architectural, social and historical context, while stressing its heightened importance for this very age and for the future.

Eye Level Memory

Text: Levente Szabó

Photo: Piotr Strycharski, Bartosz Haduch

After the traumas of World War II and the Holocaust, which are slowly fading into obscurity, many long decades were needed, and still will be needed for the presence of the abstract, centrally-dictated remembrance narratives in the built environment to be replaced by something else: by personal and locally valid, grass-roots approaches to the substantially complex process of remembrance. “Not the result of the activities of higher powers, instead starting from eye level, from you and me.” defined Jochen Gerz, designer of numerous definitive memorial projects called counter-monuments. [James E. Young: The Counter-Monument: Memory against Itself in Germany Today, in: Critical Inquiry, The University of Chicago Press, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Winter, 1992), pp. 267-296]

It was James E. Young who referred to them as such in an interview when describing the effect mechanism of such memorials, particularly of these forms of remembrance act. It is the eye-level viewpoint that necessarily creates the possibility of something gaining a personal quality, and all this seems to be the only option for the memorial projects of the beginning of the 21st century.

Just a few kilometers from the incomprehensible scale of the traumatic memorial landscape of the former Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, a small-scale memorial park has been created in the historical center of the town known as Oświęcim in the Polish language as a memorial to the Great Synagogue that had stood between 1863 and 1939, and to the former local Jewish community brought to life by its remembrance.

I visited the two memorials one after the other over the course of a single day in April 2022. The many layers of shocking or even commonplace memories, of historical information, texts, films were replaced by personal, visceral experiences. The huts and ruins of the former camp had a simultaneous, alienating effect: in the dense lines of the tourist groups I was just one of the mechanical “memorial consumers” driven by the tourist guide, while in the secluded grounds of the Oświęcim memorial park myself and a few others had the opportunity to get to know the history of the place and soak up its atmosphere. After the memorial landscape of the concentration camps with their obviously global, universal symbolic strength, I visited a memorial park that first seemed to have just local validity, commemorating the local community. And how this is not the case, and how the remembrance of this tiny, local story matures to the general level of memorials is the main merit of the memorial park. It is the paradox of the difference in scale between the two experiences that really points out the significance and the possibilities of the spatial expression of memorial work starting from “eye level”.

There were 20 synagogues in operation in the town of Oświęcim before World War II, which is no accident as half of the population was of the Jewish faith. Similarly to most town synagogues the Great Synagogue was burnt down by the Nazis in 1939, which then had the prisoners of the concentration camp clear up the rubble in 1940. For 80 years there was nothing to mark the site of the former place of worship, and, obviously, by the end of this time there was hardly any trace of it in the collective memory. The cultural significance of the former building is summed up well by the fact that in 1925 it was the first public institution to have electric lighting installed. In other words we are at the long-emptied site of the blossoming community and cultural life of a blossoming town. This is what is being remembered and this represents the significance of the memorial park planned here.

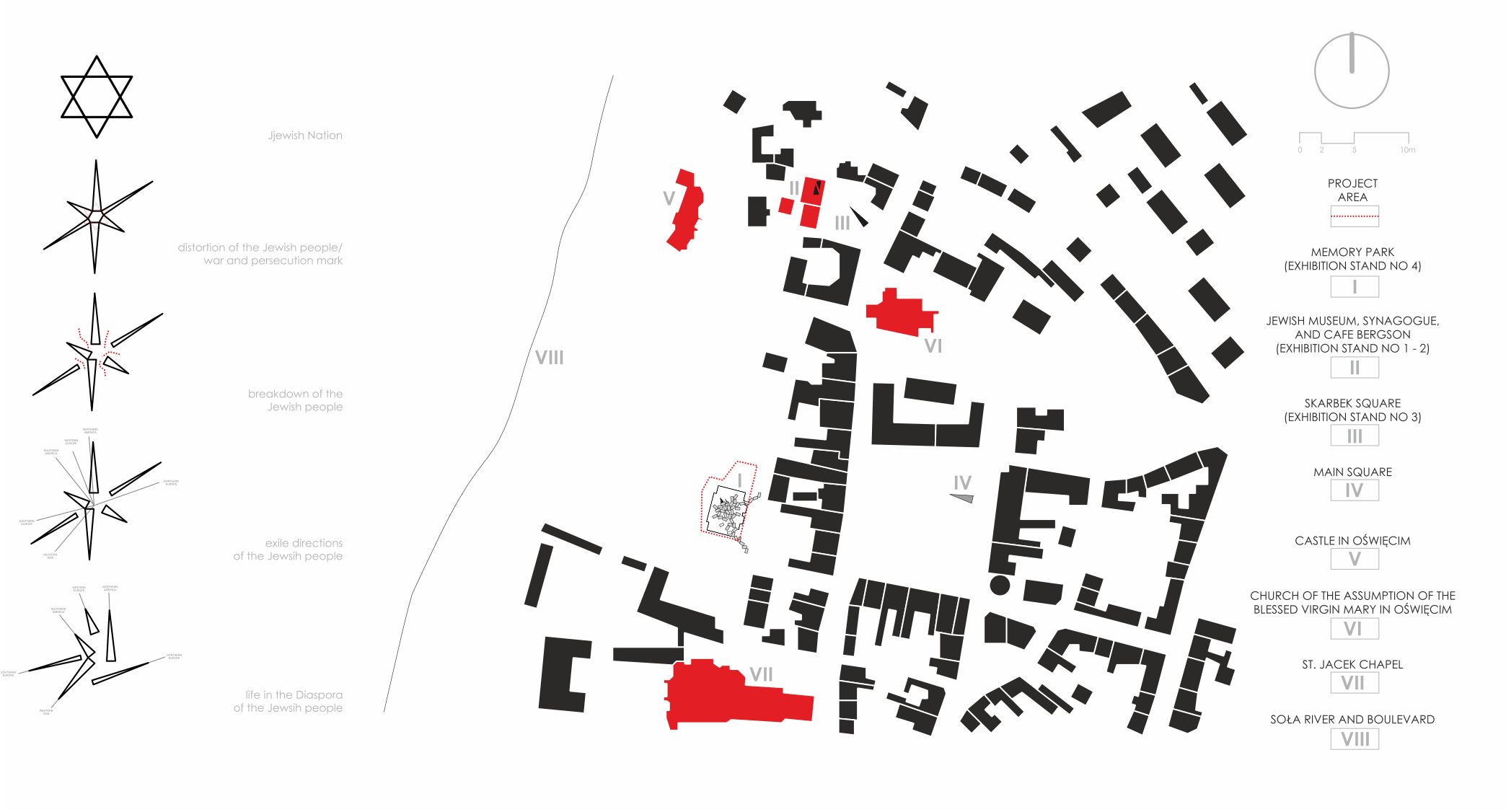

*Right: Project area: IX. Memory Park (exhibition stand no 4) / X. Jewish Museum, Synagogue, and Cafe Bergson (exhibition stand no 1 – 2) / XI. Skarbek Square (exhibition stand no 3) / XII. Main Square / XIII. Castle in Oświęcim / XIV. Church of the Assumption of The Blessed Virgin Mary in Oświęcim / XV. St. Jacek Chapel / XVI. Soła River and Boulevard

Left: Diagram of The Star Of David Jewish Nation / Distortion of the Jewish people/War and persecution mark (Breakdown of the Jewish people) Exile directions of the Jewish people / Life in the Diaspora of the Jewish people

Alive and Personal Remembrance

The single remaining town synagogue located nearby was reconstructed by Krakow-based Narchitektura, who were also responsible for the exhibition set up in it, and for the new memorial park running along the Soła river in Berka Joselewicza street. The museum is so much more than an exhibition space: the building is the base of the Auschwitz Jewish Center Foundation, which aside from its archiving work is also involved in education, maintaining a dialogue, organizing numerous public exhibitions, public area installations, i.e., facilitating the activity of memorial processes. The space empty since 1940 had remained in the urban fabric as the former location of the synagogue, as a lack, as a witness of the World War; the location of the former place of worship had been taken over by the trees and vegetation, regained by nature.

The basic concept of the memorial park appears to be a harmony among the use of elements at various scales. This is not a punctiform memorial site, but instead a composition of overlapping layers. The location of the memorial park is nature itself: in the way the bluish paintings on the ceiling of the former synagogue had symbolized the sky, today the heavens really are above the site, with the natural reality of the branches of the trees taking the place of the vaulted roof.

At the time of my visit the landscaping had not yet been fully completed: the edging marking of the contour of the former synagogue will not only be highlighted by the now blooming daffodils, but also by the planned protective ring of rich zones of bio-diverse plants to encompass them. The drawing out of the contour of a former building, the depiction of absence is a well known solution used at the locations of several examples of former Jewish religious buildings now missing from the fabric of European towns and cities. At the site of the Great Synagogue in Leipzig burnt down in 1938, local architects Sebastian Helm and Anna in 2001 designed the composition consisting of 140 bronze chairs recalling the former interior. In this same year the memorial consisting of the contour of the former synagogue in Heidelberg set out in white marble was completed. The work transforms the inner space of the place of worship that fell victim to the infamous Night of Broken Glass, along with many other European synagogues, into a contemplative urban public space. The simple yet obvious gesture of the recalling of the internal space of the religious building puts the given location back into its former status, offering those remembering today the opportunity to experience the former community use, raising the absence into the center of the remembrance narrative.

“The main idea behind the memorial park comes from an archival photo taken just after the demolition of the Great Synagogue in Oświęcim by the Nazis at the beginning of world war two,” said Bartosz Haduch, founder of and designer at Narchitektura.

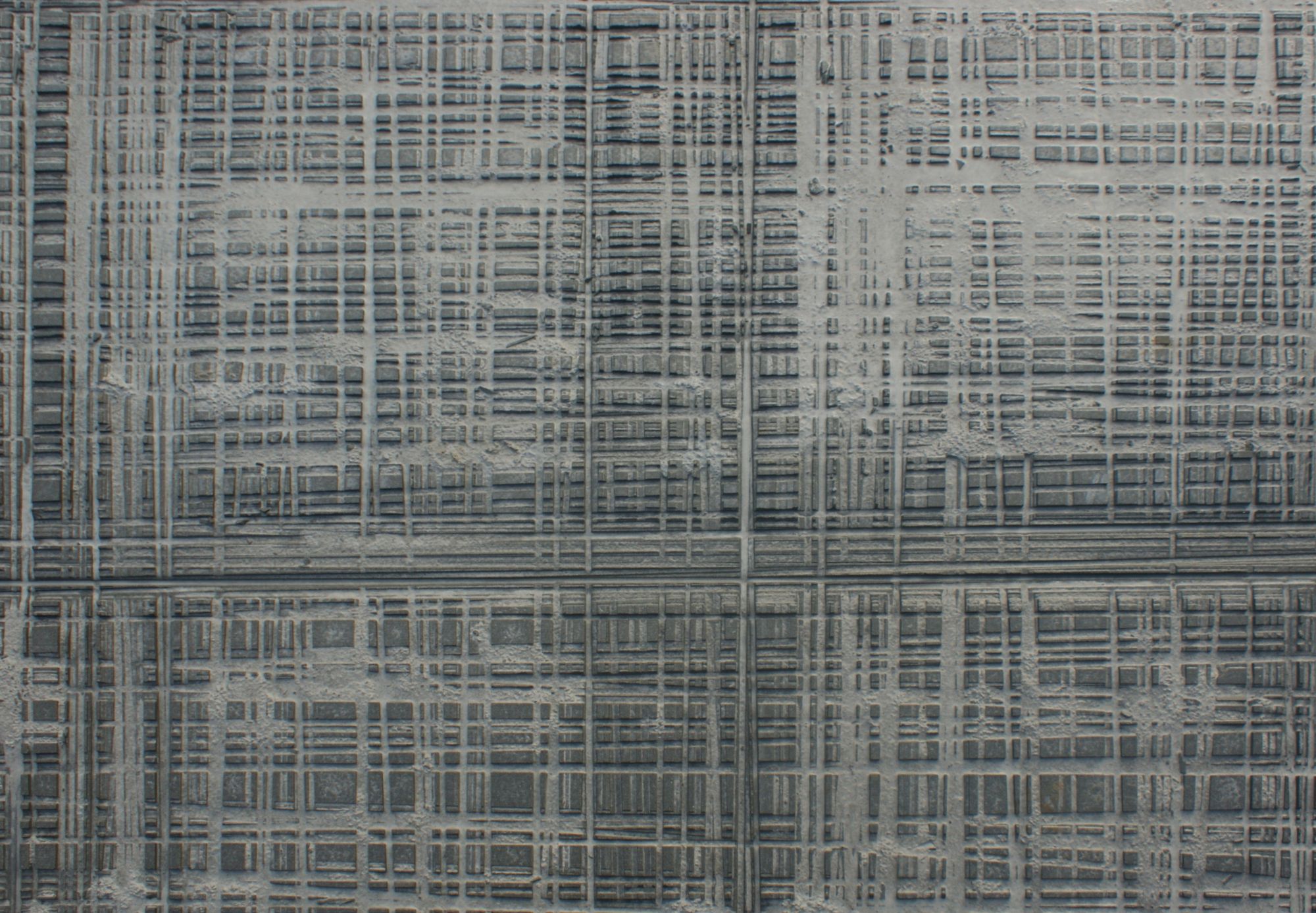

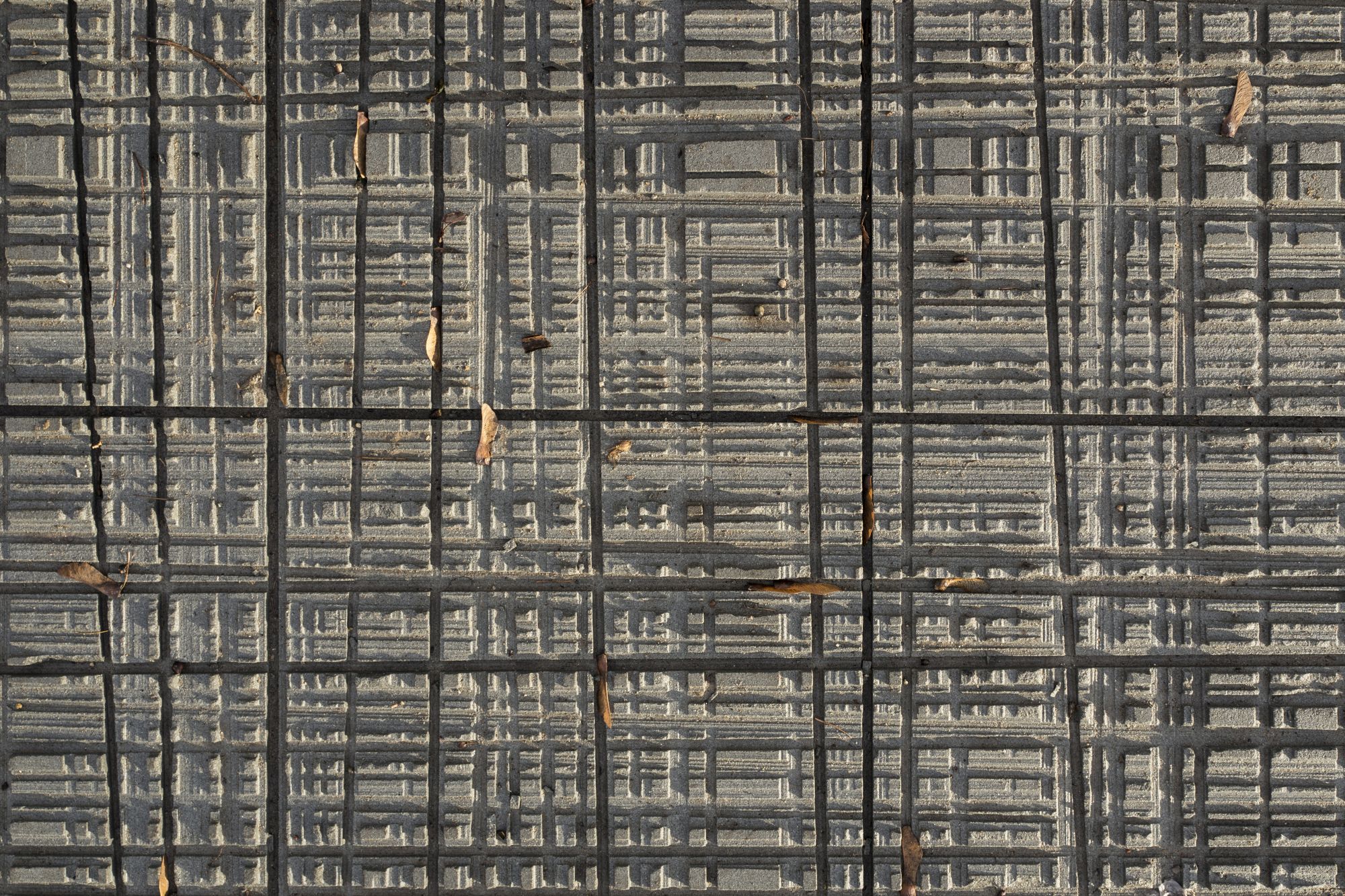

Recalling destruction, a ruinous state without false pathos is, of course, no easy task. A lucky turn that happened before the design of a memorial park 10 years previous was very convenient: the designer found 40 sandstone slabs in a quarry which had been used as the surface where they had worked the stone, due to this they were full of scoring caused by the disc cutters.

The ornamental beauty of this scoring did not come from design, but from the fact that they had had a subordinate role in the stone working processes.

The randomly positioned stone slabs, aside from the ruinous state, help bring to life a rich range of associations: the floor of the former place of worship may come to mind, or the footprints of those stepping there, or, possibly legitimately, they may evoke gravestones, a deserted cemetery.

The fact is that in spite of what we may have first believed, nothing else occurred than the adaptive reuse of industrial waste, which fundamentally reinforces the inclusivity derived from the anti-monumentality of the memorial.

Of course, the former Great Synagogue was not destroyed without a trace. The excavations performed before the construction of the memorial park brought many building fragments to the surface: a chandelier that had once hung in the synagogue, floor fragments and pieces of stone with carved zodiac signs. The elements that have remained in material reality are just as important as the imaginary projection of the spaces that had once existed in the synagogue. The uncovered finds are on display in the nearby museum, in the thoroughly documented context of the former building and the community that used it.

Nevertheless, the one floor fragment constitutes an important element of the memorial park as it helps transform the abstract nature of the architectural and landscaping elements into a palpable reality in the same way as the replica of the uncovered chandelier hanging over a small pool of water.

Apart from the marking out of the former interior space, and the summoning performed by the stone slabs and the archaeological character, an additional layer of the memorial park is embodied in its furnishings: the benches and the wedge-shaped information interface, similar examples of which may also be found in the museum and its vicinity.

Here it accommodates a model of the synagogue and an archive photograph, and provides brief information for visitors about the history of the building. The perforations in the benches outlining the signs of the zodiac represent a reference to the ornamentation on the carved stones found during the excavation. So many concealed messages that beckon you to become involved and remember, but not exclusively that, as the elements in the memorial park with their various scales in themselves are operating, full-value interventions.

The constant change of scale that the visitor experiences while wandering around the wider environment of the memorial park and among the built elements filling the interior space of the former synagogue itself once again is the best possible thing to make remembrance alive and personal. A walk in the shaded town park, the tactile experience of the scored stones, the fragrance of the daffodils, the everyday nature of sitting on a park bench, and the small archaeological signs are all, either independently of each other or in any combination, architectural or landscape elements of various scale that may be experienced and observed. It is precisely this that gives the small memorial park its strength: it leaves the method and depth of reception open, leaving it up to the visitor to experience either an everyday park or remembrance from a personal or community point of view.

In other words the work is open, in every sense of the word: spatially, as it calls up a closed space, but only on the plane of the floor plan or through the depleting composition, fragmentation of the stone slabs. But this openness is also true in the figurative sense, the freedom and diversity of reception and experience, and its concept itself leaves its interpretation open, free of narrative, and it is precisely because of this that it appears as a valid contemporary place of memorial.

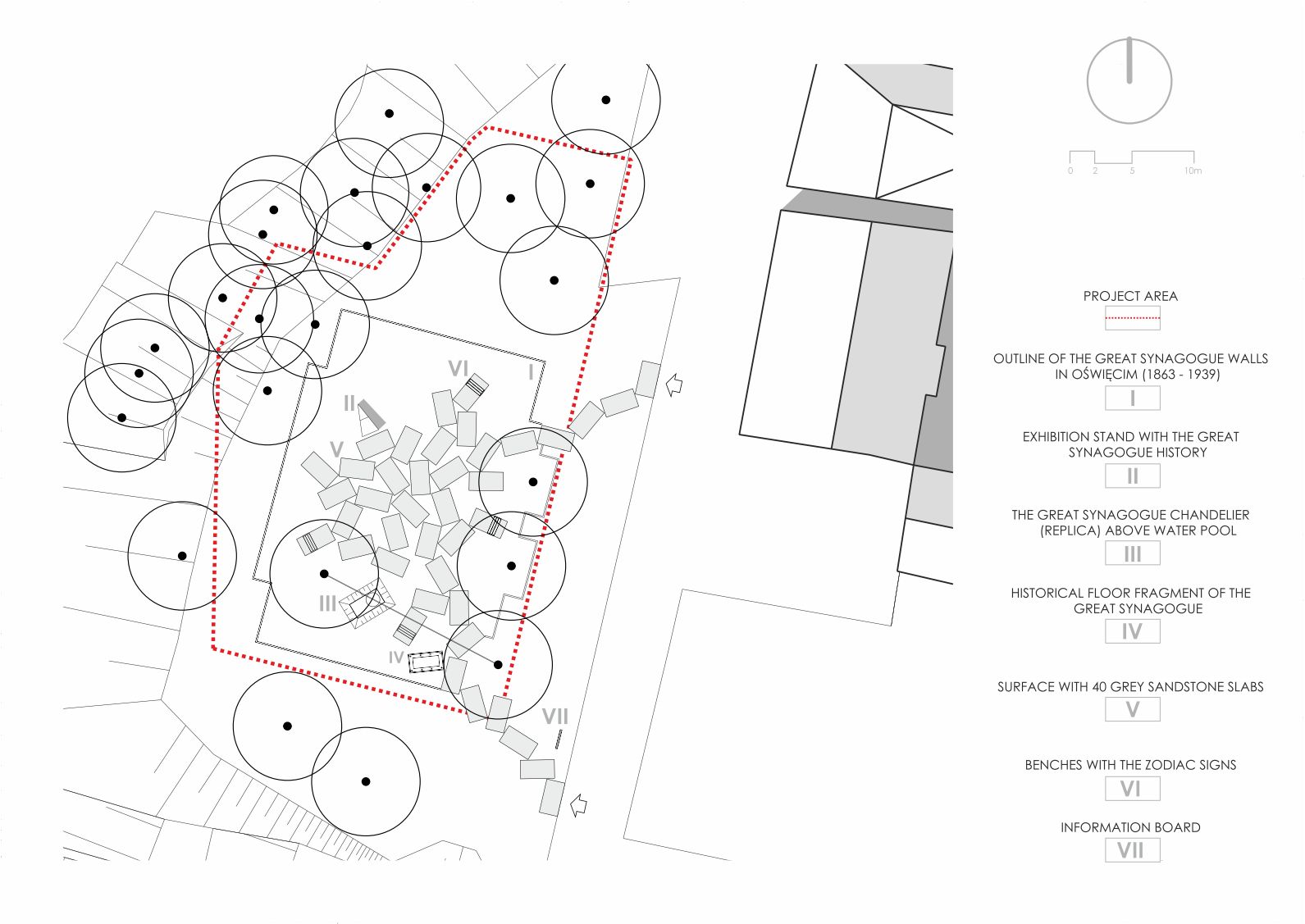

*Project area: VII. Outline of the Great Synagogue walls, 1863-1939 / VIII. Exhibition stand (history) / IX. Great Synagogue chandelier (replica) above the water pool / X. Suprafață: 40 de plăci din piatră/ XI. Benches with the Zodiac signs / XII. Information board /

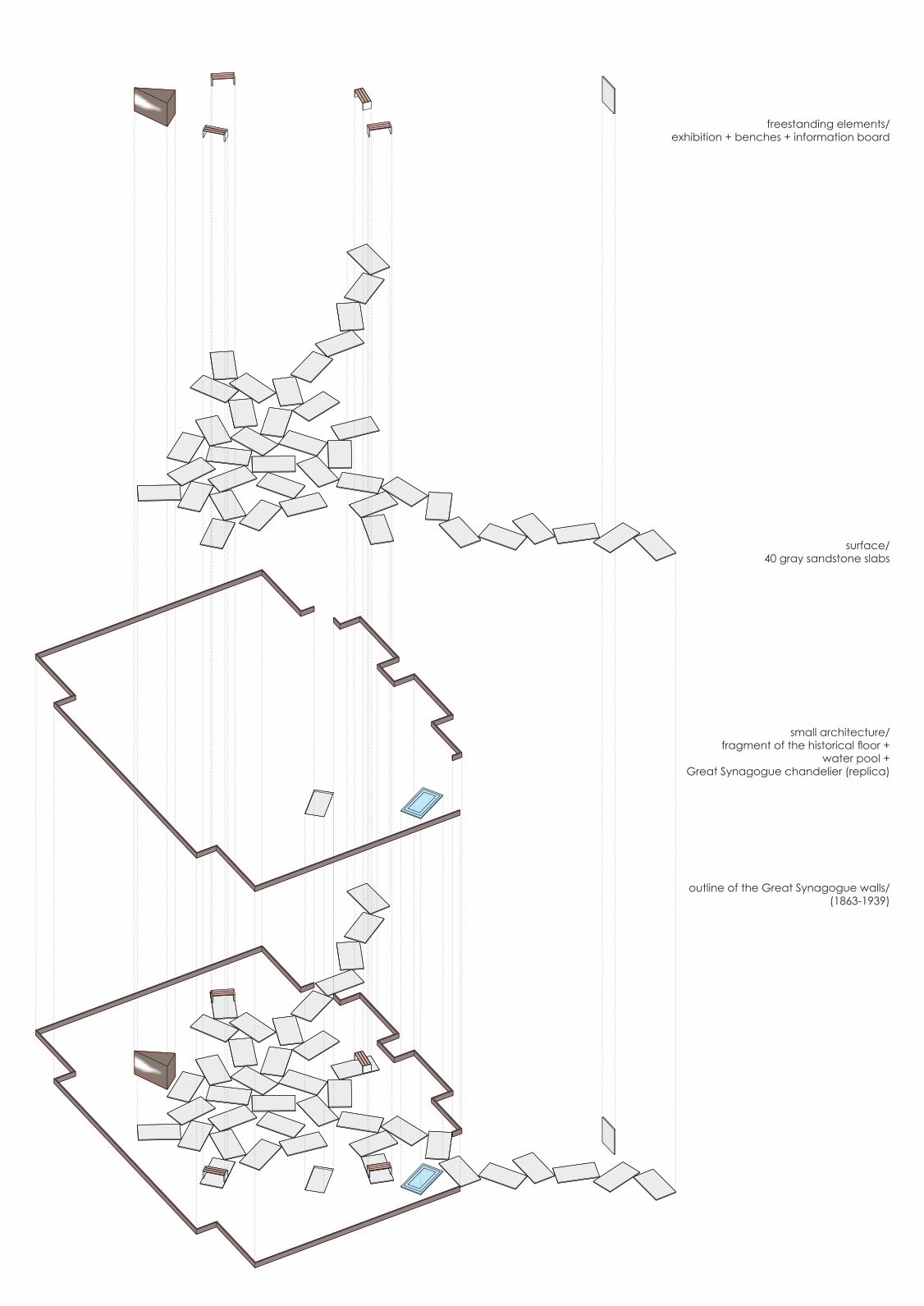

*Exploded axonometry. From top to bottom: Freestanding elements: exhibition + benches + information board / Surface: 40 gray sandstone slabs / Small architecture: fragment of the historical floor + water pool + Great Synagogue chandelier (replica) / Outline of the Great Synagogue walls, 1863-1939

The time of memorials that overwrite and govern the place has expired,

even if plenty of them are still created today to become ineffective, grotesque furnishings of our public spaces, which merely offer the illusion of reception and so are surely to become something that is just transient. Those memorial projects in which I had the opportunity to participate as designer, especially the World War II memorial on the Budapest ELTE University campus and the public area project made for the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, were also focused on inclusivity. The 1×1 cm bronze rods bearing the names of the casualties recessed into the wall, in the mortar joints of the university’s brick buildings or the text appearing in the pavement covering the square are at once both everyday and hardly noticeable, and yet still dramatic or even festive, large scale symbols integrated into the topography of the place. It very much seems that we have an increasing need for links to those chapters of the past, both the glorious and the traumatic, that may be best experienced by the community and become powerful always in the local setting, in the micro-histories, with local validity. It is precisely because of this that in the case of memorials design is best able to exert the strongest effect through a status subordinated to the local character. In the small memorial park in Poland we are the witnesses of nothing other than the very best of this responsible and sensitive design approach.

What is at stake in memorial projects today is stronger than we believed it to be a few decades, years or just months ago here in Central Eastern Europe. The war taking place nearby is reinforcing the significance of how we reflect on those historical happenings, the globally or even locally significant patterns of which we are forced to go through time and time again. It is precisely from this point of view that Oświęcim’s memorial park is most worthy of note. Its designers devoted their entire attention to the details of the place, to its history, its character then and now, and created an elevating, powerful place for the opportunity of the living remembrance of World War II and the Holocaust, which is many times forgotten with its global rituals and interpretations. At the same time they present, through the place and local validity, the universal sense and significance of the unbroken faith in humanity in a way that is always valid at the present moment, and which goes far beyond the town, Polish history, and the tragic events and losses of World War II.

*The article was written with the support of the MTA Bolyai János Research Scholarship program.

Info & credits:

Project credits:

Authors: Narchitektura – Bartosz Haduch, Łukasz Marjański

Collaboration: Imaginga Studio – Magdalena Poprawska

Landscape architecture: Narchitektura – Bartosz Haduch

Structural engineer: Maria Koczur

Electrical design: Robert Haponik

Client: Auschwitz Jewish Center