Text: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Photo: Cosmin Pojoranu

I confess that this editorial was initially supposed to be about Ukraine. Obviously, whether we speak of architecture or any other part of culture, we have no right to just go on with our activity and concerns and ignore the terrible tragedy close to us. I wanted to write about war and architecture, about the cities destroyed, about the blocks of flats and public buildings, similar to ours, that were levelled to the ground, about how the underground in Kyiv was turned into a sleeping space and about much more.

However, we have decided to do so in a more thorough and continuous manner, with informed articles, on the website and in the following issues. Not war-porn, not ruin-porn, but respectful, in-context presentations. In fact, we are starting right now: within our dossier on discreet architecture, Daniel Tudor Munteanu is speaking, in an extended, documented material, of a model-project for a rural administrative centre in Ukraine, of resilience and democratic building through architecture (as well).

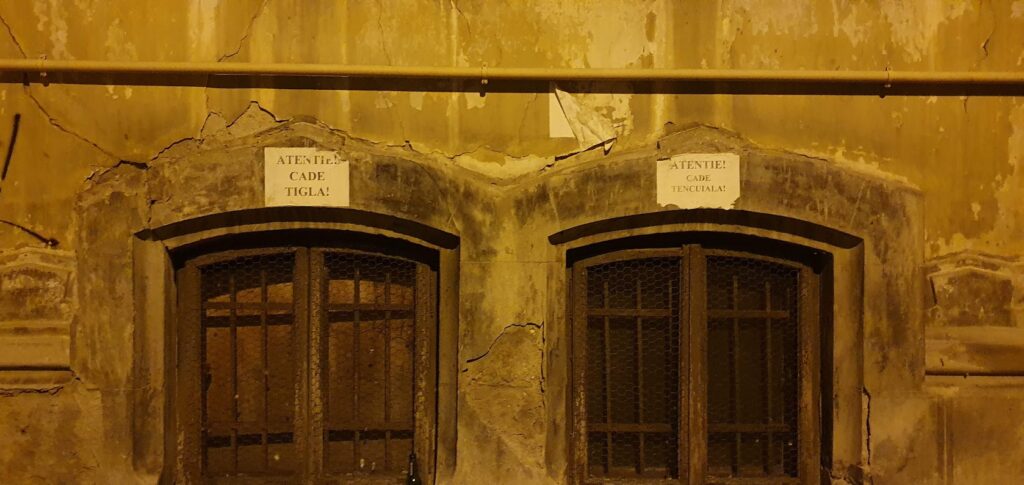

So this editorial’s topic starts from a local event, but a one significant for a phenomenon we have been obstinately writing about. Recently, right on the street I take to reach my office and the University, a piece of plaster fell right on a little boy’s head. He got a bad wound, he was taken to hospital, and I really hope he’s alright now. Well, we already know, like my colleague Cosmina Goagea often says, that Bucharest is a city that kills you. It kills you with its pollution, with its cars running you over or taking up your footways, forcing you to walk down the road, where they will run you over, it’ll kill loads of us when the next earthquake hits.

And there is very little we can do. Evidently, the legal and organizational system for the rehabilitation of old buildings is powerless. This is about funding, of course, as, when considering the general budget, the amounts are infinitesimal. But this is also about building a system which should allow for the collaboration with, and the actual aid from, local authorities. See here, this is about private property, and the state finds it difficult to invest in private property. Of course, when it comes to the thermal rehabilitation mega-program, those monuments of superficiality, non-architecture, and populism, it was possible to pass a special law that does precisely that – supports private property out of public funds. The reason is in fact something rather simple: programs such as the insulation I mentioned, but also operations related to curbs and walkways being rebuilt 24/7, to the tens of thousands of playgrounds, to flower beds, etc., have two essential qualities: the money is easily and quickly spent, with simple procedures, and the effects are large-scale and can be immediately seen. The people taking the money are happy, the politicians are happy – results are seen during their own mandate, people get the feeling things are being done. But at the same time cities go hang.

Obviously, we, architects, also have our (big) share in all this. But you only have to take a look at the legal butchering of the position of chief architect and at the elimination of honest and competent people from heritage-related structures, to realize that the lack of good actions is not only about incompetence and populism, but also about our structural corruption.

Now, it is clear that the solution lies mostly with orchestrated pressures, with instrumentalizing the civil society’s indignation and stress to pressure the authorities. But beware: we should not be fall for partial, hasty solutions. I, for one, can imagine a superficial and populist program (in fact, there is one already), that should be accompanied by fines (oh, we do love fines when we are not the ones paying them) and punishments, and that should, for instance, lead to massive but limited interventions to the rehabilitation of facades.

It is a type of catastrophic solution within the logic of our national patching up. On the one hand, such punctual solutions will lead to an even bigger aggression on the heritage – just consider the operations of removing hazardous ornaments and anti-architectural rehabilitations, with or without thermal insulation. Beyond architecture, precisely because the emergency is a pressing one, and because the issues are many – the next earthquake will be a devastating one, we need integrated approaches, to look at buildings overall – structure, installations, facade, roof, cultural value, but also the potential to improve the quality of living, as well as – most importantly – the program’s social aspects. It takes an economic strategy – after all, rehabilitation really does create financial value – and one to also support disadvantaged inhabitants, as well as to integrate counselling programs, to create a design system.

It is even harder for them (who are, in fact, also us) to accept and implement something like this; but coherence does not represent an improvement, a bonus, but a vital need. In any case, alongside social living and the balance to chaotic development, I can imagine nothing more important than a program today related to architecture and the city. Otherwise, the plaster will not be the only thing falling around here.