It is generally difficult to rehabilitate Modernist works, balancing unavoidably radical interventions and the respect for your colleagues’ (and even your masters’) work. How do you deal, though, with minor, (semi)vernacular Modernism, devoid of any great historical value, but full of charm – and issues? Miklós Péterffy chose to work in the spirit that had generated the old project, rather than in preserving the built substance at all costs. His project carries that spirit forward, ennobling and inspiring new life into an old and modest house.

Text: Ștefan Ghenciulescu

Photo: Balázs Danyi

Master Builder Art Deco

The house, of what back then was a rather green suburb, and today is a central district in Cluj, was built in 1936. The old plans only show the name of the master builder. It was probably also the master builder who was the author, as it was the case in many situations in inter-war Romanian, on both sides of the Carpathians. Master builders who were working with different architects for high-end projects, in city centres or in new neighbourhoods, would apply what they had seen and learned over there, to unassuming constructions on the city periphery or in the rural areas. On the outskirts or in villages, from Dobrogea to the Sub Carpathians and Moldavia, there are many such constructions, with round windows airing the attic, with stepped attics concealing ridged roofs, and with Art Deco plasterwork, applied in the wildest possible ways. “Cubism” was fashionable, and the idea or prestige and identity, associated to ‘Cubism”, had found its way deep into society. The vast majority of these constructions were made without any permit whatsoever.

In Ardeal and Banat, things were somewhat better controlled, as here there was the system of “Baumeisters” – certified for smaller scale works.

This was pretty much the case for this house: as Miklós Péterffy puts it, a master builder attempted to work very much like a good tailor who studies fashion magazines carefully. It was definitely not a capital A Architecture, but there was a certain romantic charm, that touched both the customer buying the house, precisely to rehabilitate it, and the architect.

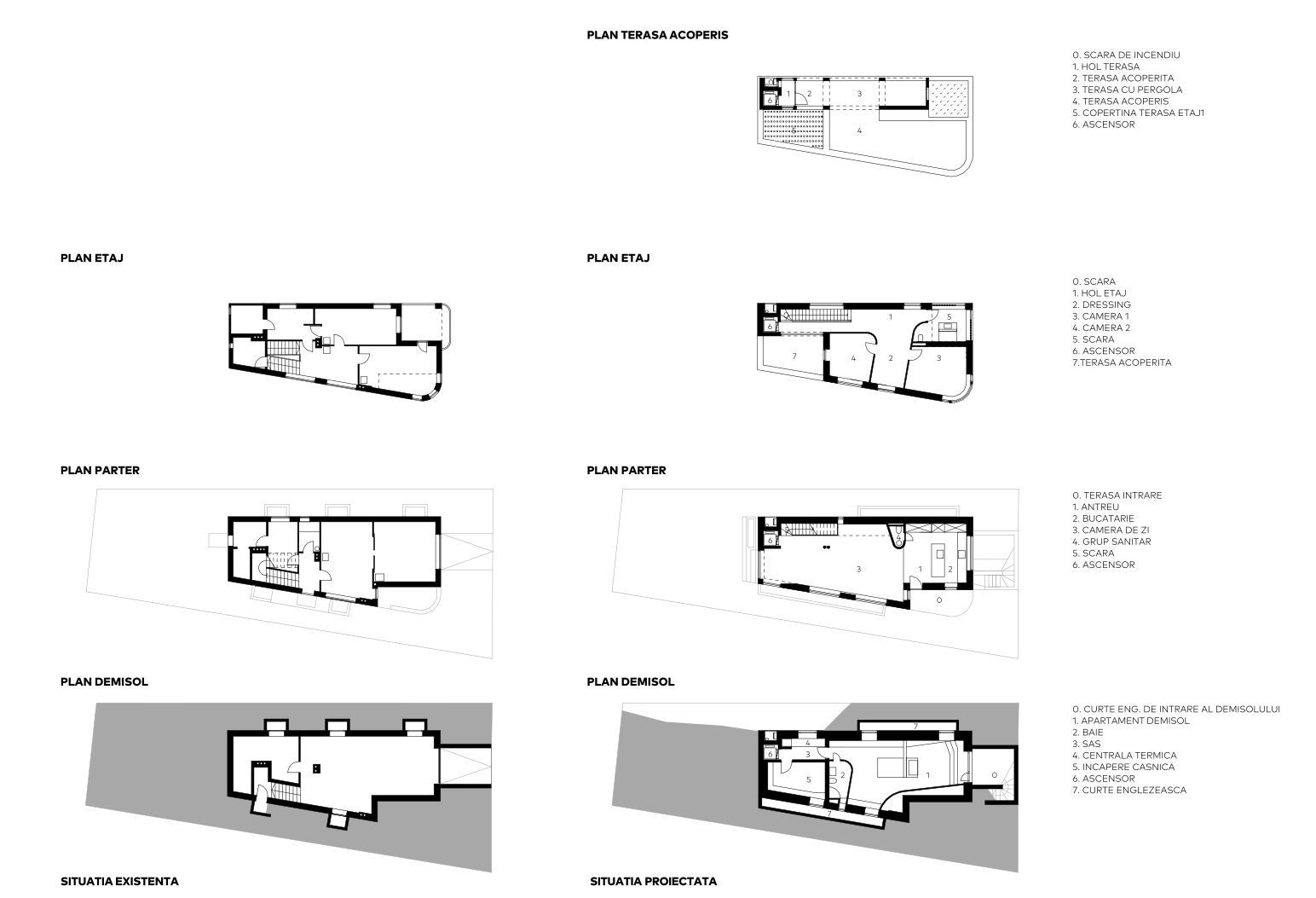

However, beyond the technical shortcomings and the degradations inherent to a long life, the building also had big functional issues. Some are due to prioritizing representation, therefore the good, noble, facade towards the street, to the detriment of orientation and interior logic: thus, the completely enclosed staircase took up the place with the best light (southwest) and the opening towards the garden (which was otherwise also occupied by the kitchen, placed, again, at the back), while the master bedroom on the ground floor would open towards the street, pushing the lounge towards the lateral side of the plot. Upstairs, the two bedrooms would also open mostly towards the north, and they were too narrow anyway. The only terrace upstairs, that was open towards the back yard and the light, had been transformed in the meantime into an additional room.

Radical upgrade

The obvious needs for a correct and comfortable living entailed a massive intervention. Once this decision was made, both the exterior and a set of radical interior changes were up to discussion. In fact, the question became not how to fix and improve the house, but what was there still to keep.

For the architect, the most valuable and essential element for the house’s character was the curved corner in the southeast. This, and the desire to preserve the general outline, would generate the re-thinking of spaces and image.

*before and after

After the rehabilitation, the basement lost the garage. But there appeared a large sunken courtyard and two smaller linear ones, allowing for a small studio with an independent access, as well as for some new technical rooms. On the ground floor, the services and the circulations are now naturally aligned on the northern side, freeing a general space with slight separations between the kitchen, access and living space, and allowing the opening of all the rooms towards the sun and towards the garden.

On the 1st floor, the elevator and the staircase lead to two bedrooms, a bathroom and an open dressing, treated as a living space, and to a covered terrace that also oversees the garden. Finally, the old roof is replaced by a partial 2nd floor, consisting of a series of open, covered, or semi-covered terraces. The view of the city (the entire neighbourhood is on a slope) is impressive, and the classic Modernist dream of the garden roof is spectacularly achieved.

New/Old Modernism

Somehow, it seems to me that the transformation of the roof expresses very well the general design strategy. The important weight of new elements allowed Miklós Péterffy to re-think the entire architecture. The result is a surprising 21st century Art Deco. No, this is not a pastiche. Although you recognize the characteristics of the style (the geometry, the profiling, the joy of both modernity and ornament, the optimism, the warmth and the belief in a tamed progress, that were so specific for the period), the details are clearly contemporary. This carrying on is very visible in the metal joinery for instance, but also in the curved window, very much like the builder masters of the time would have wanted it, if they had the technology for it.

The continuous space, the way how furniture becomes architecture and how architecture dresses you like a comfortable coat, the high-quality materials and the finesse and preciousness of details, speak both of the reference period, and of a sort of moderate and timeless Modernity. Elements such as the exposed concrete further anchor the image into our age.

This being said, this is clearly a different house, and you cannot help but wonder about the general validity of such a type of intervention in an old building. This is a difficult problem, as it is very difficult to balance reconstruction as such of old elements (which we are reticent in accepting in restorations of classical architecture, for instance), with assumed contemporary interventions, a more sincere option, but one that risks damaging the character of the original architecture. Romania (and not only Romania) is unfortunately full of brutal transformations of inter-war heritage. Can you, on the other hand, as a today’s architect, design in an Art Deco “Style”?

In this very particular case, I would say that the architectural answer is a legitimate, fresh, and responsible one. First, precisely because, as I was saying above, this is not a pseudo-Art Deco house, but a house that continues and develops, in its own sensible way, the Art Deco principles and aesthetics. Regarding the relationship with the existing, the new house starts in a fundamental way from the old one, which it incorporates and transforms. Miklós Péterffy would never think to design a completely new house in this manner. It is just as sure that he would never change the image of a coherent Modernist villa of considerable value, however bad its condition may be. We see here a very fine balance between what is valuable and indispensable, and what can or really should be re-invented. And there is also the quality of the result, the way, and not just the principles of doing architecture.

Sustainability would also be a topic: it becomes important here not just by the presence and architectural integration of thermal insulation (although this presented the architect with a lot of problems, especially around the openings and in places where several materials meet), but also, and especially, through preservation. The greenest house is still one that exists, is preserved, and brought to better performance.

The PJ House is not and should not become a general mode of intervention on interwar architecture. But it is a beautiful house, one that makes you feel good, and yes, a very good model of interrogating the history of architecture and how important it is to strive to preserve an old building, no matter how humble, and to discover and outline its hidden values.

Info & credits

Address: Str. Bisericii Ortodoxe 38, Cluj

Construction: 05.2015–11.2018

Architecture: Miklós Péterffy

Structure: Dáné Rozália

Installations: Fábián Levente – Conex Instal

General Contractor:WEBERBAU SRL – https://www.weberbau.ro/romana/portofoliu/restaurare-casa-art-deco-in-sec-xxi.html

Hydro-insulation: BAUDER – www.bauder.ro